Introduction

Often, what is called ‘old’ implies uselessness. The cognitive templates it possesses can no longer make sense of the present, or ‘new’, social reality. One simple way to establish something is now old, or out of use, is to investigate whether, or not, there is a certain degree of mismatch between the presently encountered social, economic or political phenomena and the available stock of knowledge. The Middle East, this paper argues, is certainly not a new place to the extent that the political theater of the region is still the playing field of an unrepresentative elite whose fortune disagrees with the wellbeing of the larger population.

The communal waves tried, but failed, to alter this resilient status quo -that is true. Nevertheless, they showed to us two things. One is that peoples of this region, especially younger generations, no longer fear pushing strong men from their posts –such as Mubarak or Ben Ali. For once, it seems, Arabs broke free from their predicaments. The other is, as this paper argues, that the post-Arab Spring Middle East is already near to a threshold of change. It will most assuredly pass the threshold once those economic conditions needed for further changes in the political order, come in to force. The only alternative to this is a protracted crisis of authoritarian political economy.

The foremost condition for various Arab countries to overcome this status of limbo is to reconcile economic development with a meaningful degree of cohesion and stability within society. For them to be able to create organic relationships between economy and society, this paper propounds that they first need to divorce from the free market economy sanctified by the IMF or the World Bank. In the last three decades, the myth of self-regulating markets delivered the greatest harm to the Arab societies. Structural adjustment policies, rather than generating optimal allocation of resources, yielded catastrophic market failures, disturbed social equality, and only served the interests of the few in the commanding heights of state and society. Authoritarian elites’ false promise of rapid modernization of economies through austerity agendas only created an inapt private enterprise with no ability whatsoever to substitute for the withdrawal of state from areas of social provision. The resurgent authoritarianism in Egypt, for instance, may only hope to contain the associated social grievances, but they are far from diffusing these social tensions.

This article unfolds along the following three sections. The first section deals with authoritarian bargaining. It conceptualizes it as a social contract that previous to the era of market-oriented reforms underpinned the relationship between the repressive elites and their Arab subjects. According to that, the latter was to overlook ongoing political repression so long as material aid flows from the former in the form of subsidies, cheap credits, favors and employment.1 The second section delves into the historical circumstances that rendered the authoritarian bargain an obsolete accumulation regime. There emerged three reasons that in interaction spelled its ruin. First, the authoritarian bargain for all its popularity among the masses became unsustainable as far as that it completely subordinated the idea of efficiency to a pseudo-socialist welfare agenda. Second is immediately related to the first factor as that escalating growth of population generated an ever-enlarging demand for state-paid employment, subsidies or credits. Finally, these two factors became a pretext for business circles and a second generation of authoritarian elites –i.e. Ben Ali, Assad, Sadat and Mubarak– to enthusiastically join in the waves of the neoliberalism- as did the rest of the World.

This same section will detail out some of the underlying reasons that set the tone towards the Arab Spring. First, the authoritarian bargain did not completely go extinct. It rather (d)evolved into a new form from the 1980s onwards, one that retained the repressive character of politics, albeit debunking its state-led welfare agenda in favor of deregulation, fiscal austerity and privatization.2

Such coexistence of authoritarianism and marketization was a huge dent on the fabric of this hybrid authoritarian mode of bargain. To the extent that the rulers had to push for structural adjustment reforms without creating a democratic buffer to absorb social grievances with those reforms. The second source of fragility emanated from the fact that post-1980s Arab economies proved even less capable than their statist predecessors in dealing with demographic imbalances. The dismantling of the state-owned large industrial sector in line with neoliberal transformations caused what D. Rodrick called “premature de-industrialization.”3 Concisely, the elites’ strict adherence to neoliberal reform moved them into putting state on the sideline before replacing it with a private sector capable of absorbing the jobless youth.

Public financing of citizens’ needs is both the rationale behind the persistence of this bargain and constitutes a substitute for liberal political alternatives

The third and the final sections of this article aim to relay all these observations onto the specific cases of Egypt, Syria and Tunisia together with the historical trajectories each state has gone through, from the rise of the authoritarian bargain up to the present.

The Main Contours of the Authoritarian Bargain and Its Birth in the Arab World

To stay in power regimes need domestic legitimacy which comes in many different forms. Extending the realm of political liberties is one way of doing so, but obviously it is not the strongest suit of those political orders that take on the main contours of authoritarianism. In order to invoke loyalty in their subjects, they have to therefore create and deploy mechanisms for redistributing the aggregate national wealth.4 This way of ordering a country’s political economy is called an authoritarian bargain, some sort of a social contract between the elites and the citizens whereby the former promises substantial public spending in exchange for citizen’ absence from seeking political influence.5 It is therefore safe to assume that public financing of citizens’ needs is both the rationale behind the persistence of this bargain and constitutes a substitute for liberal political alternatives.

As part of this vassal-suzerain pattern of relationships, leading elites make a series of strategic transfers to those who can entrench their control over the military, local and national bureaucracy, business community and the ruling party.6Incumbents have in their repertoire also those specific types of policy instruments that benefit middle as well as lower echelons of society. Trade regulations and various forms of protection, for example, stand against entry of global capital into the market, accruing income to small-scale domestic industry.7They also assert a benefit from supporting authoritarian rulers if provided with subsidies, transfers and cheap credit. Workers benefit from this implicit agreement between the rulers and the masses through the provision of labor regulations and welfare programs. Further into the authoritarian model, its political economy is based around rebuilding the property order through land reforms or nationalization of private assets, which are imperative for securing peasantry’s backing of the incumbent dictator.8 Finally this type of non-democratic regime, also reliant on the loyalty of the educated middle classes, has to ensure an ever-enlarging administrative structure with employment opportunities.9 Authoritarian bargain comes down to altering the social structure, establishing a new domestic order in its place, and then turning scarce economic opportunities into assets that one cannot afford before surrendering to authoritarian political courses.

In broad strokes, authoritarian regimes of the region evolved from the elites’ pursuit of furthering their nation-making process as of the late 1970s.10 The post-colonial Arab states had two enduring sets of troubles for the newly established elites to overcome at the same time. On the one hand, they had to instigate a long period of economic growth in order to be able to generate material security.11 However, neither the economic institutions, nor the maturity of the industrial basis that they inherited from their colonial masters, were enough for them to quickly achieve this. On the other hand, they had no recourse to mobilizing masses through representative democracy. For many the reason was that newly founded states’ official identities, such as Syrian or Jordanian, were far away from competing against historically better established supra-state (e.g. Pan-Arabism) and sub-state (e.g. tribal networks) identities.12

What then came to their aid was the predominant policy paradigm of capitalist wealth accumulation: import-substitution model. This accumulation regime, as the contemporary understanding of the Cold War era, became the cognitive template of how to go about organizing the state’s role in relation to the economic field. The gist of it was to forge extensive public sectors to compensate for the absence of private employment and market-driven demand.13 A third world variant of Keynesianism, import substitution scored great success in mustering a domestic-induced industrialization and commercialization of agricultural sectors.14 The state’s new role as the principal pacemaker with decisive control over growth, prices, employment opportunities, and credit soon represented new political opportunities for the leading elites. They thereby turned this opportunity into a recurring pattern of political economy –called the authoritarian bargain. It is on this basis that, as late as the 1970s, Arab statehood already had its roots deep inside the domestic sphere as a magnet that no individual could fail to draw/stay close to without risking economic survival.15 Resultantly, the authoritarian bargain is emergent from an import substitution mode of wealth accumulation and became the much-coveted cement through which Arab subjects pay their allegiance exclusively to their respective rulers/regimes.

Such trade off, between freedom and bread, long presented a strong basis of legitimacy to the Arab state elites

Such trade off, between freedom and bread, long presented a strong basis of legitimacy to the Arab state elites. For all its impediments to the progress of democratic politics, regional Arab states owed to the authoritarian bargain low poverty rates; high enrollment rates in primary, secondary and tertiary education; the sharpest decline in infant mortality rates compared to other post-colonial places; a relatively low rate of social inequality, the provision of a nation-wide affordable health-care together with an economic environment defined by easy and well-paid employment opportunities by the state. Add to this list the state’s crucial role as a consumer, creditor and subsidizer of last resort for merchants, small-scale business and peasants.

The authoritarian bargain as a peripheral developmental strategy seemed to reach its zenith in the 1970s and then started to recede from this date on.16 This specific way of ordering politics and economics across the Arab world began to morph into a new form, which conveys hybrid characteristics of authoritarian politics and neoliberal economics. In other words, Arab states remained unchanged even after the advent of marketization reforms of 1990s in terms of their repressive character while, in the economic sphere, private enterprise (e.g. services, construction or tourism) slowly took over the space from state-tailored industry, agriculture or manufacturing.17 These shifts did not gain traction until the following two reasons transpired. One of these reasons had its roots within the domestic site of Arab societies, namely a demographic boom which swiftly expanded the population dependent on state-provided economic benefits. State elites found it increasingly difficult to afford an authoritarian bargain with their immediate, scarce economic means.18 The fiscal burden of maintaining the former populist-redistributive policies, such as subsidy programs, or absorbing the work-force into state-offices, as early as the 1970s, compelled elites to combine safe-old measures with those other ones drawn from ‘marketization’ repertoires of neo-liberal paradigms.19

The authoritarian bargain had to end for it failed to generate enough resources to accommodate a relentlessly growing number of people culturally accustomed to think of their rulers as some sort of a feudal suzerain

The second reason is related to the global structure. The economic downturn of the 1970s and the ensuing wave of neoliberalism swept aside Keynesian economics together with its peripheral variants, i.e. the Import Substitute System, upon which the political economy of the authoritarian bargain was built. Or, better-said, it was an established consensus between those national capitalists with strong ties to global circuit of capital and a new generation of elites that exploited a possibly temporal economic stagnation to win over their statist rivals and organized masses.

Note that not all Arab countries felt the same amount of pressure from these structural vulnerabilities –e.g. population boom. For that matter, one needs to draw a line of separation between two versions of authoritarian bargain taking into account that market-oriented reforms hit the shores of only some of the Arab regimes –e.g. Egypt and Syria. Other countries of this geography, such as Saudi Arabia or Kuwait, became at best slightly exposed to the waves of neoliberal change20 in the 1990s even though they too had to cope with a similar demographic shift under the limitations of an authoritarian bargain. The Arab Spring devoured the political geography of only middle and low-income countries. In the absence of revenues from lucrative energy reservoirs, this selection of countries had to instead shower protestors with water cannons.

As S. Haggard and R. Kaufman underline, authoritarian bargains of all sorts are susceptible to economic bottlenecks.21 Supply shortages, a grinding economic growth, or a rapid devaluation of currency exert pressure on those key economic assets that authoritarian elites desperately need in order to lock in public support behind their order.22 The odds are that leaders who keep in their possession vast energy wealth have a better chance of pulling through times of severe economic hardships.23 Citizen’s loyalty to their regimes is certain to remain as the continual flow of financial means that make it possible to enable generous welfare programs, thereby eliminating calls for liberal political/economic reforms. The so-called “crisis strata”24 –a situation whereby masses are more inclined to rise against their rulers due to economic deteriorations– generally hits hardest those incumbents that are without the economic means for appeasing public discontent. Caught in between a rock and a hard place, this version of authoritarian rule is compelled to go either in the direction of repression or political compromise.25

The Saudi House, in the middle of the 1970s, unlike its cash-strapped counter-parts in North Africa or Old Levant, was riding on the back of quadrupling oil prices, which endowed them with all the possible fiscal resources to steer clear of an eventual domestic rupture. Neither now, nor then, did they need to call into question the authoritarian bargain, safe in the knowledge of their new petro-dollar wealth. Egypt, Jordan, Syria and Tunisia comprise the ‘rest’ which did not enjoy this sort of “country specific capital” to persist in original foundations of authoritarian bargain. On the onset of the Arab Spring, once again, the oil-rich authoritarian regimes were in the possession of massive foreign reserves thanks to the upward momentum in global energy prices and tight supply markets of the previous term. During and in the immediate aftermath of the crisis, Saudi Arabia was to inject some of its huge accumulated wealth into the domestic economy, which successfully isolated the Kingdom from the rest of the Arab world shaken by revolutionary zeal.26 According to the Economist, government spending in Saudi Kingdom rose by 50 percent in between 2008 and 2011 in response to the early signs of social protest.27 In the same vein, the Regime is set to give new impetus to the economy by increasing investment by half a trillion USD, a move which obviously aims to absorb the unemployed masses.28 Similarly, the UAE put together a stimulus plan that entailed the funneling of more than 40 Billion USD into the economy.29 Thus, this paper will analyze the case of the three poorest countries, namely Syria, Tunisia and Egypt, that had no option but to continually adapt their authoritarian bargain to better address their never-ending fiscal limitations.

The Authoritarian Bargain, Reloaded

Authoritarian rules, as the time passed by, started to encounter severe limitations on their ability to further state capitalism in so much as that the economic means available to them were far outpaced by a continually rejuvenating demographic composition.30 In other words, the authoritarian bargain had to end for it failed to generate enough resources to accommodate a relentlessly growing number of people culturally accustomed to think of their rulers as some sort of a feudal suzerain. What followed this was a different type of authoritarian bargain that grew more capable of furnishing certain public goods in high demand, such as employment for youth, yet much less willing to do so.

Widespread marketization in the economic structures of Syria, Tunisia and Egypt produced two outcomes that set the wheels for the subsequent Arab upheavals. First is the emergence of a market place to underpin an increasingly repressive state structure. As a result, Arab capitalism has become identified with corruption as state elites failed to devise regulatory measures to curb/combat cronyism.31 The legal order upheld by reforming Arab leaders has become a mere shield protecting those who enjoy particularistic ties to the social alliance of political and economic elites. Even in this new (neoliberal) era, export licenses, financial credits, tax reliefs or state-funded construction projects were extended to those who proved politically dependable and trustworthy.32

Corruption is responsible for a shrinking basis of legitimacy with which to consolidate stable domestic orders across the Middle East

In the run-up to the revolution, what ignited the masses’ frustration with political leadership was the perceived association among clientelism, GDP growth and deteriorating living conditions. On the one hand, even though limited in scope and breadth, marketization of Arab economies have stoked a visible degree of economic growth –6.2 percent on average across the Middle East and North Africa (MENA).33 But, because of the state’s lessened control over the mechanisms of redistribution, the wealth of the privileged few expanded next to a much less impressive improvement in the daily lives of the middle and lower classes.34 Worse still, corruption is responsible for a shrinking basis of legitimacy with which to consolidate stable domestic orders across the Middle East. The steps taken in the direction of economic opening and deregulation came down on stripping the unrepresentative rulers of their former capability to compensate repressive politics with material wellbeing. Neoliberal economics laid bare the authoritarian character of their rule, casting them in the images of a happy minority whose exorbitant prerogatives piled up on the widespread misery and disappointment of the powerless majority.

Indeed, what could have been an appropriate action was to allow for venues that people could use to articulate their discontent with socio-political changes. The authoritarian nature of the state afforded few, if any, channels for voicing frustration with all that economic reforms which brought about socio-economic miseries and dislocations. The Arab youth became the main victims of the said transformations as having almost no access to the emerging clientelistic networks. Thus, it is this selection of populace whose anger had to immediately be taken into account. A right step in this direction was probably to permit the conventional operation of democratic institutions and let them diffuse the young people’s sense of marginalization and exclusion.

Second, as D. Rodrik asserts, an abrupt departure from state capitalism to one of an open economic model advised by the IMF or World Bank paved the way for “premature de-industrialization.”35 De-industrialization of the region’s non-oil rich states can be measured by the extent to which this selection of countries, such as Syria or Egypt, has increasingly become reliant on service-based industries. The overall share of this type of economies from the national GDPs of the non-oil rich MENA, on average, surpassed 50 percent in the middle of the last decade.36 However, touristic or financial endeavors were no match for the volume of employment that manufacturing, agriculture and industrial plantations used to cover in the previous era. Another aspect of de-industrialization was import-oriented growth defined by a divorce from the protection of local industries against external competition. The inflow of foreign merchandises quickly suffocated mid-sized and small-sized enterprises and, therefore, built huge current account deficits.37 The Arab exports, on the other hand, only became weakened as a consequence of shrinking consumer outlets in Europe amidst the Eurozone crisis.38

Privatization is another link in the long chain of de-industrialization, a process that went hand in hand with the retreat of the Arab statehood from its formerly assumed responsibilities as a last resort of credit and employment. Public companies, the main vehicle through which the states of the region provide employment opportunities for the educated middle classes, were put in a disadvantaged position with the pursuit of neoliberal macro-economic policies. One of the critical steps taken in this direction was the recalibration of tax laws across the Arab world. In Egypt, for instance, a new regulation held state companies liable for returning 40 percent of their total turnover to the government’s pockets, whereas privately owned enterprises were held responsible for only paying a flat rate of 20 percent tax.39 In the name of heartening the privatization, this new legal order handicapped the state enterprises while spontaneously accelerating the wealth of the few who had no commitment to social stability.

Hence, all of these structural adjustment policies functioned to reduce the state’s role, thereby, creating two explosive outcomes. Firstly, Arab elites by imprisoning the authoritarian bargain into the narrow confines of structural adjustment policies inadvertently added more pressure to the ongoing crisis of employment/population mismatch.40 Market oriented reforms were waves that shoved the authoritarian bargain into a protracted crisis, constituting a major restraint on those resources needed for the sustenance of state-society relationships of the Cold War era.41 Secondly, political authoritarianism denied those who suffered from neoliberal reforms, especially the Arab youth, political voice to discharge their grievances. In the following section, all these inferences will be applied to three post-Spring Arab states: Tunisia, Syria and Egypt.

Syria: A Failed Revolution

Syria’s total population grew almost four times from roughly 6 million in 1970 to 22 million in 2010.42 The pace of this growth from 1980 onwards has never been below 3.5 percent per year.43 One should also consider the fact that life expectancy has climbed from approximately 60 years to that of 75 years in a relative short span of time between 1970 and 2010.44 Presently, close to 60 percent of the population is between 15 to 24 years old, an interesting piece of data, taking into account that the same group in the 1970s was roughly 40 percent.45 Demographic change over the period has obviously created a young bulge. It is also obvious that the Syrian regime has endured significant troubles in creating new job outlets since youth unemployment in this country is currently 6 times larger than the overall unemployment rate.

Giving more insights into Syria’s situation, this country, in terms of per capita GDP growth, made limited advances46 from 1983 to 2003 within a pressing demographic setting, which required accommodating an already doubled young labor force.47It must be noted that 77 percent of all unemployed in Syria, in 2002, was from young populace, and 75 percent of jobless youth had already been seeking employment for over a year.48 These figures were already alarming in the pre-reform era as youth joblessness was almost double the global average of 14 percent in 2002.49

Facing a constantly growing supply of young labor from the 1980s onwards, no less than 5 percent in the said period,50 the Syrian government sought ways to flee from an eventual social crisis. At the turn of this century, the Assad regime in consecutive steps moved to rebuild its reign of accumulation, but without altering its authoritarian character. These economic reforms started to change the appearance of the country by driving it towards a “social market economy.”51 One leg of these transformative policies was public sector employment retrenchment. It had the objective of reducing budget deficits through undercutting state-paid jobs which resulted in a sharp decline in the number of positions and wages to be offered by the public sector. The second leg was to make space for the private enterprises by means of changing the restrictive legal framework to their entrance. The regime, as the third dimension, embraced deregulatory policies within the labor market, thereby getting rid of formerly provided legal backing of the employed vis-à-vis employers. As fourth, Damascus also partially released itself from its commitment to free education, healthcare and some other safety nets, such as oil subsidies, in this new era.

De-industrialization in the Syrian case proved completely counter-productive and corrupted in the process, while reducing state’s role to a level from which Assad’s regime could no longer sustain popular support

However, these attempts at reinvigorating the economic growth by appreciating a certain degree of autonomy to market players, proved an ill-advised game plan. In a country where young people need to have powerful connections when it comes to attaining employment in public offices, a relatively large fiscal spending is a must to permit it to happen. According to a report, Syrian youth’s economic behavior weighs heavily in favor of working as a state employee –more than 80 percent.52 If so, shifting the economic weight away from state towards private sector proved ill-advised, considering that the state employed more than 80 percent of all educated youth whereas the private sector has never accounted for more than 20 percent of the same category.53

Turning to the political consequences of this choice made by the Baath regime, from 2005 onwards, de-industrialization in the Syrian case was based on a trade-off between fostering a national capitalist class, that proved completely counter-productive and corrupted in the process, while reducing state’s role to a level from which Assad’s regime could no longer sustain popular support for the established rule. All in all, without a parallel move towards liberalizing politics, a more liberal economic order foremost upset lower and especially middle classes whose support has always been imperative for the sustenance of the regime in Damascus. One way of looking at this misplaced endeavor is to check macro-economic indicators of the previous years.

Syria’s already incomplete industrialization halted at the start of the century and then dwindled to negligible quantities after the Country’s integration with Gulf economies and, through Turkey, Europe in 2008.54 The prospects for furthering its high tempo economic growth, about 5 percent between 2005 and 2008,55 became elusive after opening to the outside world, which strangled Syrian agriculture, manufacturing and industry. The only standing branch of activity was tourism, which, as stated earlier, did little to absorb the said growth of unemployed youth.56 Attention paid to services or tourism came at the expense of agriculture, manufacturing and industry. For much the same reason that construction can only deliver a short-lived impetus, tourism and services are known to produce no positive affect on fixed-capital accumulation. The Syrian economy is no exception to these rules.

In the period from the advent of reforms to upheavals in 2011, government revenues declined by a staggering 9 percent57: a mixed outcome of declining tax revenues, loss of state-induced economic activity and soaring unemployment. Correlating all these with the situation in the labor market for the same period of time reveals the essential reasons for public unrest. The Syrian population in this era grew by almost 25 percent and the youth population seeking jobs was not in short supply –with a one-third increase from 2005 onwards.58 Even the overall unemployment was on the rise from 8 percent to 9.5 percent in 2011,59 despite the ongoing outflow of emigrants to Gulf countries. GDP per capita seemed to make headways lifting from $4,000 to approximately $4,500.60 However, such increase had yet to produce a trickle-down effect with poverty increasing by almost 10 percent in the same period of time.61 Furthermore, even those lucky enough to be included in state-paid employment had seen almost no increase in their real income in the face of increases in inflation. The said erosion of real incomes should also be mentioned as it signifies that the Assad regime turned to monetary expansion in a bid to cover loss of employment: a measure that can only be sustained in the short-term. Just like all other Arab regimes, Syria now endures a constant growth of fiscal deficits.

Amidst this sea of changes, Syria’s authoritarian rule almost stood intact. In the elites’ perception, economic reconfigurations would further fortify their social order. Just as other incumbent rulers of this geography had done, the Assad regime mistakenly relegated neoliberal reforms into matters of technical significance, as new ways of reproducing pre-reform status quo. The harsh response to the public protests in 2011 was heralding of both how badly the regime failed to discern mounting social grievances and how unprepared they were to manage the situations through a degree of political compromise. Some sort of political opening had to be initially placed next to painful economic changes because the former was needed to relieve the pressures emerging from the latter. Market-oriented reforms, without changing role expectations that Syrians have from their state, created an unfair and deeply polarized society, namely the widening gap between those few benefitting as opposed to the many million losers. Democratic politics was the sole tool to bridge this gap, had it not been removed from the table with the eruption of upheavals.

Tunisia: An Unfinished Revolution

As in the case of Syria, here too all possibilities to sustain authoritarian bargain exhausted themselves long before the beginning of social upheaval and the ensuing regime change. But, unlike Syria where the regime left behind no space for a smooth political transition, Tunisia is in a far better place.

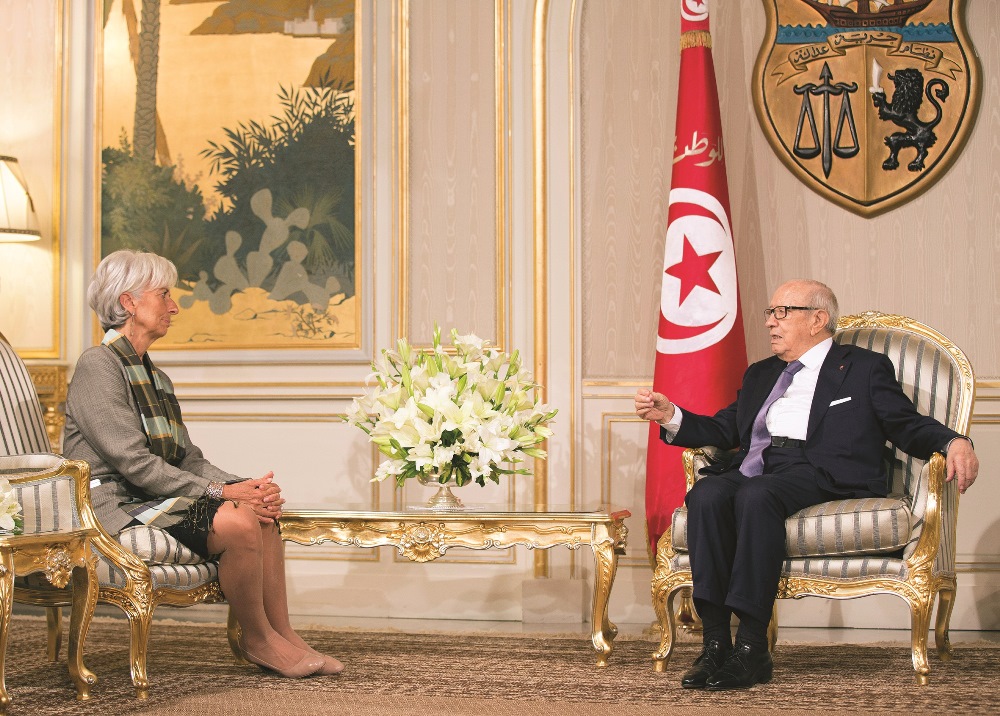

IMF Chief, Christine Lagarde, met with Tunisian President Beji Caid es-Sebsi and urged Tunisia to press ahead with the “vast number” of pending economic reforms on September 08, 2015. | AFP PHOTO / STEPHEN JAFFE

IMF Chief, Christine Lagarde, met with Tunisian President Beji Caid es-Sebsi and urged Tunisia to press ahead with the “vast number” of pending economic reforms on September 08, 2015. | AFP PHOTO / STEPHEN JAFFE

The Tunisian-breed of authoritarian bargain was founded in the 1970s in a bid to strengthen the incumbent authorities’ monopoly over the various echelons of the society. Again, as part of this pattern of relationship between the state and non-elites, population seldom questioned their lack of freedom in exchange for state employment, public healthcare or low taxation. Then in the late 1980s came the double-barreled problem of declining productivity of state-engineered industry and the resultant inability of the state to cover educated youth’s desire for greater employment opportunities. According to the statistical data, Tunisian population overall has seen a major growth from 5 million to 8.2 million in a relative brief amount of time between 1970 and 1990.62 Global circumstances only aggravated the economic position of this North African country with a serious domestic deadlock. The main provider of touristic income and demand for Tunisian export merchandises, European markets, were still dealing with the throes of the economic downturn of the 1970s.

The early 1980s is the critical juncture at which the predecessor of Ben Ali, Bourguiba, then the president of the country, turned to the IMF and World Bank for external financing.63 These institutions, then and even today, have pursued the same policy line of conditioning the loan on the degree to which Tunisia’s authoritarian rulers stick to structural adjustment programs. To be precise, the said reformist agenda proved successful in expanding the economic output from this date on but with the apparent cost of undermining the principle of social justice.64 It involved reducing fiscal transfers from the government to the economically impoverished portions of the society; lowering/removing the remaining capital controls, eliminating the protective commercial practices, and devaluating the purchasing power of Dinar. In addition the Tunisian leader had to accept an end to subsidization of wheat and other basic food stock.

The deadly bread riots, in 1984, forced state elites to part accompany with IMF and its ‘best policy’ directions.65 Nevertheless when Ben Ali captured the power with a coup, he rushed to reinstate the IMF’s austerity agenda. When Ben Ali took the help, in 1987, he actually had need of solving the most taxing issue: depleted foreign reserves. To do so, he brought his country’s economy back into the IMF’s and World Bank’s orbit to remain there for almost quarter of a century. Retrospectively speaking, Ben Ali’s economic program was a nothing less than what N. Klein would name the “Shock Doctrine.”66 He could successfully exploit the state’s deep engagement with the market place and all the restructuring of the economy as a pretext to maintain his one-man rule.

The political and economic setting of the country slowly narrowed down Ben Ali’s domestic rule by pushing large majorities under the line of poverty while operating only to secure the wealth of a privileged few

Of the greatest concern is that the austerity agenda never delivered the promised benefits –such as increasing the competitiveness of the Tunisian economy- but instead dismantled state-pulsed economic structures without replacing them with a credible alternative. All this happened simultaneously with a demographic shift, a load that the country increasingly fell short of shouldering at the turn of the 21st Century. To be more precise, more than three million people were added to the Tunisian population, constituting a 30 percent increase from 1990 to 2011.67 Another indication, the change of life expectancy in Tunisia, displays a similarly gloomy picture: it increased from nearly 50 years to above 70 years from the 1980s onwards.68 Finally, the youth population which was little more than 30 percent in 1980 began to undergo a mind-boggling change forming more than 65 percent by 2011.69 The youth, one-fifth of 11 million Tunisians, had the highest share of unemployment –40 percent.70 This ratio has never sunk under this level –one of the highest in the world over the past 20 years.

The Tunisian economy is bereft of means to ably respond to this demographic pressure despite all the improvements in per capita income which is twice as much as what it was in 1990.71 The reasons for such are manifold but nothing different in essence from those that were already scrutinized in the Syrian case. First, Ben Ali’s regime, in order to sustain a deepened control over the country’s economic life, used a large variety of inhibitive measures to limit private enterprise. The members of the ruling family on its own could reap one-fifth of all profits made by the private economic activity in the country, which surely caused the distaste of foreign investors.72 Preferential treatment was often given to the companies controlled by the ruling family against both domestic and foreign competition. The consequence of this unfairness was the sheer lack of competitiveness in those sectors that the family sought fortune, making it extremely tough for new firms with more employment opportunities to enter them. In sum, the political and economic setting of the country slowly narrowed down Ben Ali’s domestic rule by pushing large majorities under the line of poverty while operating only to secure the wealth of a privileged few.

Second, nepotism was the instrument by which the ruling elites provided economic benefits and employment. Employment was a bargaining chip that the regime thought of providing only in return for the masses’ retreat to political complacency. However, taking into account that 85 percent of all jobless people were under the age of 35 in Tunisia,73 it was not an effective strategy to deal with demographic challenges. Ben Ali’s repressive regime was simply caught by surprise at the turn of the new century with no preparation whatsoever to be able to make space for the ever-increasing number of university graduates. By the end of 2010, one-fourth of university graduates were outside of the active work force.74 The third factor behind Tunisia’s apparent failure in reigning in its demographic challenges is that guaranteed and well-paid employment by state-owned enterprises started to lose steam after the turn taken for de-industrialization in the post-1990 period.75 A sign of premature de-industrialization is the share of service sector from the overall national wealth rising above 60 percent in 2011, whereas the same ratio for agriculture declined to a dwindling 8 percent.76 Just as happened in Syria, the private sector had neither the will nor ability to soak up torrents of new entrants. One of the bedrock reasons for Ben Ali’s ultimate demise, in 2011, is that his personal rule was not well-positioned to satisfy young Tunisians, which, resembling their same-age group in Syria, are inclined to pursue career opportunities in formal/public sectors.

Tunisia is one of the few countries in the region with a smooth transition towards a more representative form of politics. Many praised this country as the last garrison of hope for a democratic future. The long-oppressed masses, including Tunisian youth, emerged as the new players within the domestic theatre; a post-revolutionary civil society has already gained substantial momentum from the removal of Bel Ali’s repressive state and the introduction of democratic principles –such as checks and balances. It is certain that Tunisia as the sole, true survivor of the popular upheavals is a source to inspire similar changes elsewhere in the Arabic-speaking world. What is not so certain is the degree to which Tunisia’s newly elected leaders can continue this momentum under the distress of various economic problems. With the advent of democracy, and the first democratic constitution in the Arab world, Tunisians are now allowed to express their dissent and difference within democratic platforms. As stated earlier, Ben Ali’s economic agenda failed to proceed due to the fact that state repression existed alongside ardent moves towards neoliberal reforms, causing pain among the masses.

The wealthiest 5 percent was in control of close to the half of all Egyptian GDP, whereas 45 percent of the country’s stock market shares became the private property of no more than 20 families

The real problem for the time being is that the newly elected government had no option but to retain the same-all tightening agenda. The Tunisian leaders of date have turned to the IMF and World Bank in hope of financing the country’s escalating current account deficits, which, if not countered, will keep unemployment rates at its current high levels.77 Of the greatest concern is that the IMF yet again conditioned the release of additional funds on the elected leaders’ willingness to seek out further cuts from its social spending. Under the conditions, even if democracy survives, it won’t necessarily be one of a stable order, as the leaders of the country will likely face constant pressure especially from jobless youth. A high degree of unemployment, for a government that has only so much economic means to deal with it, risks the rise of populist movements by taking advantage of democratically held open channels to expression/spread of thought. Tunisia has already been exposed to one such challenge emanating from Jihadist currents.

Egypt: A Reversed Revolution

The eruption of anger in Tahrir Square, in 2010, has a long historical trajectory. The ordinary Egyptians’ deteriorated life conditions had already spawned more than 100 protests in 2007-2008.78 But intensifying economic problems alone only partially explains the genesis of revolution. Equally relevant is the political repression that became the main vehicle for the perseverance of a social order that worked to the favor of only the privileged few. The Egyptian case then is easily relayed on the same analytical model that was used to explain the Tunisian and Syrian revolutions. Accordingly, sustained repressive practices in combination with widely perceived exclusion from economic rewards were what mobilized revolutionary fervor of Egyptians against their autocratic rulers. This perception of people about ‘what has to go’ is not groundless in consideration of the following statistical data. The wealthiest 5 percent was in control of close to the half of all Egyptian GDP, whereas 45 percent of the country’s stock market shares became the private property of no more than 20 families.79

British Prime Minister David Cameron reacts during a joint press conference with Egyptian President Sisi following their meeting inside 10 Downing Street in London on November 5, 2015. | AFP PHOTO / ANDY RAIN / POOL

British Prime Minister David Cameron reacts during a joint press conference with Egyptian President Sisi following their meeting inside 10 Downing Street in London on November 5, 2015. | AFP PHOTO / ANDY RAIN / POOL

When A. Sadat’s policy of al-infitah (openness) in 1974 came about a deadlock was pressing Egypt hard –that is, to cater for a rapidly growing number of people. According to the data, Egypt saw an astonishing 72 percent growth in the overall size of its population from 1950 to 1973.80 To be able to overcome this, a public-sector-led and inward oriented development strategy was pieced together. Exponential growth of public-driven industrialization, which literally eliminated the problem unemployment and managed to improve social justice, had to gain traction from fiscal spending in the absence of export revenues or external financing/investment. This statist and self-reliant strategy for development, however popular it was among the Egyptians, came to a grinding halt around the second half of the 1960s. The population boom rendered it too costly for the state to act as an employer/creditor/subsidizer of last resort beyond a certain threshold. Egypt’s state-led industries were slaving under the load of being over-manned and over-managed, and became a constant pressure on the state treasury since most of them were loss making ventures.81

Then came al-infitah as the forerunner of, and the template for, macro-economic endeavors that other Arab countries also adopted later in the process. Sadat had the clear motivation of re-fashioning Nasser’s version of authoritarian bargain into a new shape that was aligned with market ideals. His idealized image of westernized Egypt, he thought, would come into life once the quantitative changes in the nation’s economy proved mature enough to trigger qualitative transformations in the political sphere.82 More precisely, he aimed to vest newly emerging market players with some power so that they could clamp military and civilian bureaucracy. H. Mubarak, assuming state power after A. Sadat’s assassination, in 1981, ruled out the political dimensions of al-infitah. As the ensuing events lucidly depicted, he did not care, and still much less wanted, to see economic liberalization one day depriving the state of some of its power. He assumed, however wrongly, that an economic reform together with political relaxation would pose the risk of social disintegration, and thus had to wait for the country’s economic basis to achieve full maturity.

Structural adjustment that he initiated aimed for the growth of export industries, removal of all import substitute policies and, not surprisingly, a major reduction of state’s social expenses. The final touch on Mubarak’s austerity agenda was to speed up the privatization of Egypt’s state-owned industries. In key with this plan, his government denationalized about 300 of the largest public sector companies in the country, thereby effectively terminating the state’s long-held role as a last resort of employment.83 All these attempts at turning Egypt into an export-driven economy continued for almost three decades with the close supervision of the IMF and the World Bank.

Al-infitah as the devised solution to a greater-than-ever problem of unemployment brought in substantial economic growth, specifically in the aftermath of the 1990s. Yet, such material expansion did not translate into full employment: it actually proved much less successful than Nasserite etatism in providing employment. Egypt was populated by 38 million people by the time of the Yom Kippur War.84 Contrasting this with a population of 22 million when Nasser toppled the constitutional monarchy in 1952,85 means that the Egyptian population increased by approximately 3.5 percent every other year in this 21-year period. From 1973 to 1990, the country grew by another 20 million to 56 million: which amounts to a 2.3 percent shift in population.86 And, finally, from 1990 to 2010 Egypt became a country which housed more than 78 million: an increase of population that borders on 1.9 percent.87 These figures imply that the era that extends from 1952 to 1973, coinciding with the heydays of authoritarian bargain, faced a greater pressure from a population boom compared to the ensuing era underpinned by austerity-leaning reforms. Therefore, one would expect the successors of Nasser to better address the problem of youth unemployment. For much the same reason Mubarak, to back up his employment policies in 2010, had an economy that stood 30 times larger than what was available to Nasser in 1971,88 to provide for a population that was only four-fold of Nasserite Egypt.

The waves of privatization, monetization and fiscal adjustments in the 1980s can be qualified as successful in so far as that they precipitated a ten-fold increase of per capita income up until the 2010s.89 Yet, this apparent expansion only masks the heightening miseries of Egyptians and triggered no trickling-down impact to benefit the lower segments of the society. The most taxing was the declining ratios of government spending; a mixed outcome of dismantling of large state companies, liberal tax reforms, and endemic unemployment.90 For the 15 to 24 age group, unemployment escalated to 20 percent rendering housing expenses to inhibitive for them to even consider marriage.91 As of the 2000s, the regime was enduring a deep legitimacy problem as the majority of the people saw their leadership both detached and confined, a rich minority upon which they had little to no control. To them the elites’ visibly growing wealth was because of the fusion of political authority and burgeoning market economy out of which (they felt) they were being deliberately held. Therefore it is not surprising that almost half of the monetized debt was made ready for the use of those few families who threaded personal ties to Mubarak’s authoritarian rule.

When A. Sisi restored Egypt to its former political shape and military tutelage, he enjoyed backing from the international community

Mubarak lost power because the political economy he ran for at least two decades was ineffective in removing the tight nexus of rising levels of poverty and political authoritarianism. He could have attended to the support of his people by either endowing them with economic security or relaxing his political repression with a degree of democracy. M. Morsi’s short term, from 2012 to 2013, embodies that economic recovery can survive only if it co-exists with a degree of calm political environment—or vice versa. He had to pursue economic recovery under the limitations of an incredibly unstable domestic theater. Much the same, from palace to the prison, he had only a year to consolidate political stability and solidify fragile alliances under the conditions of a volatile economy. This unstable and fragile political environment sharply delimited his maneuvering space to deal with a budget deficit of 40 percent with so little contribution from foreign workers’ remittances, tourism and outflowing foreign finances and investment.92

When A. Sisi restored Egypt to its former political shape and military tutelage, he enjoyed backing from the international community, both tacitly (from the Western countries) and openly (from Saudi Arabia). Saudi petro-dollars were especially, even if temporarily, helpful in saving the country’s economy from an inevitable meltdown.93 But such a bailout is not going to produce permanent solutions to any of the economic or political problems that the country presently faces. The monetary cushion Sisi obtained from counter-revolutionary monarchies seemed to earn him some time to engage with youth unemployment. He is in favor of a big state and grand construction projects, such as opening a new sea-lane across the Suez Channel, although it is highly dubious whether he can cover a youth unemployment rate of 35 percent94 with those resources given to him in return for his repression of the Arab Spring.95 He has already used up some of that economic help in order to reign in escalating current account deficits, currently close to 4 billion USD.96 Still awaiting is an even greater turbulence when one considers that declining oil prices will soon remove some of the enthusiasm in the Gulf to keep their authoritarian ally in Egypt above water.

Societies don’t move in the direction of liberal politics just because they found ways to oust their unrepresentative leaders

Egypt’s most taxing problem is still youth unemployment. More than seven hundred thousand young Egyptians enter the job market every year.97 Neither Egypt’s overburdened public sector nor the poor levels of private investment is anything that can alleviate this pressure: most of the educated young people, as a result, pursue low-paid jobs in informal sectors with no prospects of career development.98 Sisi is prone to face the ramifications of the continued exclusion of youth from job opportunities, just as his predecessor did previously.

Conclusion

This article’s main aim was to analyze why the Arab Spring could deliver only a limited hope for a democratic future across the Arabic-speaking part of the Middle East. The following findings came out in establishing a model of understanding as regards to this puzzle. The first one of them is: democracy is not the opposite symmetry of authoritarianism. More precisely, societies don’t move in the direction of liberal politics just because they found ways to oust their unrepresentative leaders. The Arab Spring, wherever it took place in the Arab Middle East proved it a myopic intellectual vantage point to presume that people’s desire for a self-rule, appreciated in a plural form of politics, will suffice to defeat the evils of authoritarianism.

Secondly, in order to move beyond the current stalemate, the regional people have to forge a whole new developmental path that is aligned with social peace and cohesion. In other words, the neoliberal age has to end. Because, the role it gives to the states of the region has created an economic reality that is insensitive to the needs of Arab societies. Arab countries are still challenged by a demographic boom, which cannot be appropriately responded to without the state’s stabilizer role as a last resort of employer, subsidizer and provider. Neoliberalism is misplaced to take on this challenge with its religious commitment to the idea of self-regulating markets.

For regional people to be able to embrace democracy as a credible alternative to authoritarian politics, democracy has firstly to be crowned with economic stability. As K. Polanyi once put it lucidly, there is no such thing as market economy and democratic politics existing in two separate universes.99 Syria has to wait for the end of its domestic strife to figure out ways to run both of these (politics and economics) in communication with one another. Sisi seems to be far from redefining economics in a way as to support democratic change, as his rule is basically an attempt at reincarnating authoritarian bargain. Even Tunisia’s democratic government may not move in this direction since they still seek a partnership with the IMF, which is all for severing ties between politics and economics.

Third, it must also be considered that such change of mindset cannot be achieved in the Arab world in isolation from the wider global system. There are signs to make one believe that orthodoxy in managing the political economy of nations is losing steam as of the financial meltdown of 2008. Deregulated financial capital or marginalization of state as a mere regulatory body has been pinpointed as the cause of recent economic traumas. Overall, the Arab Middle East cannot be exempted from what takes place outside the region. In the Middle East and elsewhere in the world, humanity will either step in what Polanyi called “Great Transformation”100 or, alternatively, rerun the past courses of action to repeat the same mistakes returning to the same situation.

Endnotes

- Raj Deasi et al., “The Logic of Authoritarian Bargains: A Test of a Structural Model,” The Brooking Institution, Working Paper 3, (2007), p. 4.

- L. Carl Brown, International Politics and the Middle East: Old Rules, Dangerous Game (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1984), p. 3.

- Dani Rodrik, “Premature De-industrialization,” NBER, Working Paper, (2015), retrieved October 11, 2015 from http://www.nber.org/papers/w20935.pdf.

- Daron Acemoglu and James A. Robinson, Economic Origins of Dictatorship and Democracy (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2005), p. 25.

- Eva Bellin, “The Robustness of Authoritarianism in the Middle East: Exceptionalism in Comparative Perspective,” Comparative Politics, Vol. 36, No. 2 (2004), p. 141.

- Carles Boix, Democracy and Redistribution (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2003), p. 39.

- Ibid, p. 42.

- Bellin, “The Robustness of Authoritarianism in the Middle East,” p. 47.

- Aziz Chaudhry, The Price of Wealth: Economies and Institutions in the Middle East (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2004), p. 61.

- Ronald Wintrobe, The Political Economy of Dictatorship (New York: Cambridge University Press, 1998), p. 184.

- Raymond Hinnebusch, The International Politics of the Middle East (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2003), p. 36.

- Ibid.

- Robert Cox, Production, Power and World Order: Social Forces in the Making of History (New York, 1987).

- See Lisa Anderson, “The State in the Middle East and North Africa,” Comparative Politics, 1987, Vol. 20, No. 1, pp. 1-18.

- Barry Buzan and Ole Waver, Regions and Powers: The Structure of International Security (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2003), p. 4.

- Raymond Hinnebusch and Anoushiravan Ehteshami, The Foreign Policies of Middle East States (Colorado: Lynne Rienner Publishers, 2002), p. 3.

- Angela Joya, “The Egyptian Revolution: Crisis of Neoliberalism and Potential for Democratization,” Journal of African Political Economy, Vol. 38, p. 369.

- David Skidmore, “Civil Society, Social Capital and Economic Development,” Global Security, Vol. 15, No. 1 (2001), p. 64.

- Ibid, p. 65.

- Tarik Yousef, “Development, Growth, and Policy Reform in the Middle East and North Africa since 1950,” Journal of Economic Perspectives, Vol. 19, No. 3 (2004), p. 94.

- Stephan Haggard and Robert Kaufman, The Political Economy of Democratic Transitions (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1995), p. 43.

- Ibid, p. 44.

- Chaudhry, The Price of Wealth, p. 71.

- Juan Linz, Totalitarian and Authoritarian Regimes (Boulder, CO: Lynne Rienner Publishers, 2000), p. 36.

- Ibid, p. 36.

- Mehran Kamrava, “The Arab Spring and the Saudi-led Counter-revolution,” ORBIS, Vol. 56, No. 1 (2012), p. 98.

- “Arab Spring Cleaning: Why Trade Reform Matters in the Middle East,” Economist, (2012), retrieved October 12, 2015 from http://www.economist.com/node/21548153.

- Guido Steinberg, “Leading the Counter-Revolution: Saudi Arabia and the Arab Spring,” German Institute for International and Security Affairs, (2014), retrieved October 14, 2015 from http://www.swp-berlin.org/fileadmin/contents/products/research_papers/2014_RP07_sbg.pdf, p. 9.

- Christopher Davidson, “The United Arab Emirates: Frontiers of the Arab Spring,” Open Democracy, (2012), retrieved October 11, 2015 from https://www.opendemocracy.net/christopher-m-davidson/united-arab-emirates-frontiers-of-arab-spring.

- Steve Heydemann, “Social Pacts and the Persistence of Authoritarianism in the Middle East,” Oliver Schlumberger (ed.), Debating Authoritarianism: Dynamics and Durability in Non-Democratic Regimes (Stanford University Press: Stanford, 2007), p. 19.

- Stephen King, The New Authoritarianism in the Middle East and North Africa (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2009), p. 79.

- Heydemann, “Social Pacts and the Persistence of Authoritarianism in the Middle East,” p. 45.

- Nadine Sika, “The Political Economy of Arab Uprisings,” European Institute of Mediterranean, (2012), retrieved October 12, 2015 from http://www.euromesco.net/images/papers/papersiemed10.pdf, p. 12.

- Ibid, p. 14.

- Rodrik, “Premature De-industrialization,” p. 4.

- “Towards a New Social Contract in MENA,” World Bank Middle East and North Africa Region, (2015), retrieved October 09, 2015 from http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/2015/04/24334919/mena-economic-monitor-towards-new-social-contract, p. 9.

- Pete Moore, “Fiscal Politics of Enduring Authoritarianism,” Project on Middle East Political Science, (2015), retrieved October 7, 2015 from http://pomeps.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/03/POMEPS _Studies_11_Thermidor_Web.pdf, p. 26.

- Sika, “The Political Economy of Arab Uprisings,” p. 13.

- “Reform Agenda: Expected Changes to the Tax Law,” Oxford Business Group, (2012), retrieved October 11, 2015 from http://www.oxfordbusinessgroup.com/analysis/reform-agenda-expected-changes-tax-law.

- Ragui Assad and Farzaney Roudi-Fahimi, “Youth in the Middle East and North Africa: Demographic Opportunity or Challenge?” Population Reference Bureau, (2007), retrieved October 08, 2015 from https://prb.org/pdf07/YouthinMENA.pdf.

- Deasi et al., “The Logic of Authoritarian Bargains,” p. 4.

- “Syria Population 2015,” World Population Review, (2015), retrieved October 16, 2015 from http://worldpopulationreview.com/countries/syria-population/.

- Ibid.

- Sika, “The Political Economy of Arab Uprisings,” p. 5.

- “Demographic Profile of Syrian Arab Republic,” (2015), retrieved October 11, 2015 from http://www.escwa.un.org/popin/members/syria.pdf.

- “Syria GDP Per Capita,” Trading Economics, (2015), retrieved October 11, 2015 from http://www.trading economics.com/syria/gdp-per-capita.

- Ibid.

- “Youth Exclusion in Syria: Social, Economic and Institutional Dimensions,” Journalist’s Resources, (2011), retrieved October 11, 2015 from http://journalistsresource.org/studies/international/development/youth-exclusion-in-syria-economic.

- Ibid.

- “Demographic Profile of Syrian Arab Republic.”

- Bassam Haddad, “The Political Economy of Syria: Realities and Challenges,” Middle East Policy, Vol. 12, No. 11 (2011), p. 48.

- Nader Kabbani and Noura Kamel, “Youth Exclusion in Syria: Social Economic, and Institutional Dimensions,” Wolfensohn Center for Development, (2007), retrieved October 10, 2015 from http:// journalistsresource.org/wp-content/uploads/2011/08/Youth-Exclusion-in-Syria.pdf, p. 14.

- Ibid.

- Haddad, “The Political Economy of Syria,” p. 54.

- Ibid.

- Ibid, 58.

- “Country Report: Syria,” (London: Economist Intelligence Unit, 2010), p. 5.

- Nader Kabbani and Noura Kamel, “Youth Exclusion in Syria,” p. 21.

- Ibid.

- “Syria GDP Per Capita,”

- Haddad, “The Political Economy of Syria,” p. 57.

- “Demographic Profile of Tunisia,” (2015), retrieved October 11, 2015 from http://www.escwa.un.org/popin/ members/tunisia.pdf.

- Rob Prince, “Structural Adjustment: Former President Ben Ali’s Gift to Tunisia,” Foreign Policy in Focus, (April 23, 2015), retrieved October 11, 2015 from http://fpif.org/structural_adjustment_former_ president_ben_alis_gift_to_tunisia_part_one/.

- Mehdi Shafeddin, Trade Liberalization and Economic Reform in Developing Countries: Structural Change or De-industrialization,” UNCTAD, (2005), retrieved October 11, 2015 from http://unctad.org/en/ docs/osgdp20053_en.pdf.

- Naomi Banhidi, “Political and Economic Perspectives of the North African Transitions: Economic Challenges for Egypt and Tunisia,” Institute of International Studies and Political Science, (2012), retrieved October 11, 2015 from https://btk.ppke.hu/uploads/articles/554378/file/Szakdolgozat percent20MA percent20Ba percentCC percent81nhidi percent20Noe percentCC percent81mi percent20Evelin.pdf, p. 55.

- See Naomi Klein, The Shock Doctrine: The Rise of Disaster Capitalism (London: Picador, 2008).

- “Demographic Profile of Tunisia.”

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- “Addressing Youth Unemployment in Tunisia,” Tunisia Live, (March 24, 2014), retrieved October 11, 2015 from http://www.tunisia-live.net/2014/03/24/addressing-youth-unemployment-in-tunisia/.

- “Tunisia GDP Per Capita,” Trading Economics, (2015), retrieved October 12, 2015 from http://tr.trading economics.com/tunisia/gdp-per-capita.

- Banhidi, “Political and Economic Perspectives of the North African Transitions,” p. 57.

- Margaret Bohlander, “The Youth Unemployment Crisis in Tunisia,” CIPE, (November 18, 2013), retrieved October 10, 2015 from http://www.cipe.org/blog/2013/08/16/the-middle-east-youth-bulge-where-is-it-today/#.ViRLZ6QyE-9.

- Ibid.

- 7Banhidi, “Political and Economic Perspectives of the North African Transitions,” p. 57.

- “Economic Profile of Tunisia,” Trading Economics, (2015), retrieved October 10, 2015 from http://tr.trading economics.com/tunisia.

- Prince, “Structural Adjustment.”

- Banhidi, “Political and Economic Perspectives of the North African Transitions,” p. 34.

- Tarek Osman, Egypt on the Brink: From Nasser to Mubarak (London: Yale University Press, 2010), pp. 115-116.

- “Egypt’s Population,” Worldometers, (October 12, 2015), retrieved October 12, 2015 from http://www.worldometers.info/world-population/egypt-population/.

- Saleh Abdelazim, Structural Adjustment and the Dismantling of Egypt’s Etatist System, Ph.D. dissertation (Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University, 2002), p. 40.

- Sika, “The Political Economy of Arab Uprisings,” p. 14.

- Abdelazim, Structural Adjustment and the Dismantling of Egypt’s Etatist System, p. 105.

- “Egypt’s Population.”

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- “GDP: Countries Compared,” Nation Master, (2015), retrieved October 12, 2015 from http://www.nationmaster.com/country-info/stats/Economy/GDP#.

- “GDP Per Capita: Countries Compared,” Nation Master, (2015), retrieved October 11, 2015 from http:// www.nationmaster.com/country-info/stats/Economy/GDP/Per-capita.

- Saleh Abdelazim, Structural Adjustment and the Dismantling of Egypt’s Etatist System, Ph.D. dissertation (Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University, 2002), p. 114.

- “Demographic Profile of Egypt,” (2015), retrieved October 11, 2015 from http://www.escwa.un.org/popin/ members/egypt.pdf.

- Feliz Imonti, “Morsi, Egypt Face Economic Meltdown,” Al-Monitor, (August 27, 2015), retrieved October 11, 2015 from http://www.al-monitor.com/pulse/originals/2013/01/economy-egypt-morsi-revolution.html#.

- Kamrava, “The Arab Spring and the Saudi-led Counter-revolution,” p. 98.

- “Unemployment, Youth Total,” Data World Bank, (2015), retrieved October 11, 2015 from http://data. worldbank.org/indicator/SL.UEM.1524.ZS.

- “A Dud Return to Democracy,” Economist, (October 10, 2015), retrieved October 12, 2015 from http://www. economist.com/news/leaders/21672217-president-abdel-fattah-al-sisi-taking-egypt-down-familiar-dead-end-dud-return-democracy

- Ibid.

- “Egypt: Tackling Youth Unemployment,” The Guardian, (August 3, 2011), retrieved October 09, 2015 from http://www.theguardian.com/global-development/2011/aug/03/egypt-education-skills-gap.

- Ibid.

- See Karl Polanyi, The Great Transformation: The Political and Economic Origins of our Times (Boston: Beacon Press, 2001).

- Ibid.