Introduction

Throughout history humans have formed a vast variety of different groups based on countless different criteria, which are used to distinguish ourselves from one-another. We have the natural tendency to divide ourselves into “us” and “them” often on characteristics conditioned by space and time. These characteristics and distinctions that divide us constitute our different identities. Among many other characteristics, ethnicity and nationality are prominent parts of identity. They are often forged through history and are quite closely related to territory. In Grosbys’ words: “The nation is a territorial relation of collective self-consciousness of actual and imagined duration.”1 In fact ethnicity and nationality are so closely related to the territory they inhabit that most people share simultaneously the same name with it. It is hard to say whether the names stem from the people or the territory but what is important to us is that people are perceived and perceive themselves accordingly. For example we have Japan the territory and Japanese its people, Germany-Germans, Egypt-Egyptians, Brazil-Brazilian, Canada-Canadian, etc.2 In Kosovo and Macedonia this special relation between territory and identity has posed serious security concerns in the recent past.

The role that ethno-nationality has on the identity of the people in the WB compared to other identities is in general more dominant and, as the 1990s war demonstrated, even determinant

The term “ethnicity” is usually used to define a group of persons sharing a common cultural heritage. The latter is made by common history, environment, territory, language, customs, habits, beliefs, in short, by a common way of life. Undoubtedly, religion is an important component of any cultural heritage. In some cases it is even presented as the most crucial factor in the formation of an ethnicity and consequently of a nation.

As individuals we have many characteristics that contribute to our self-image and which overlap at all times; these characteristics that constitute our identity play different roles in our behavior without generally conflicting with each-other. Here we refer to identity, or more accurately to social identity, as the feeling and identification of individuals as part of a group based on real or perceived characteristics. On the contrary other characteristics like being a member of a monotheistic religion, our sexual identity, racial identity and of course ethno-national identity play much greater roles in general in regard to our behavior and towards that of the group. This is especially important when it comes to ethno-national characteristics since they usually prevail over others and push us into conflict with other groups with which we would otherwise identify ourselves.3 Due to the tendency of humanity to form societies with special relation to a territory, ethno-national characteristics have a more central role compared to others.4

Identity it is not an easy concept to define and neither are ethnicity and nationality; hence we find ourselves obliged to explore these concepts as well, not least because they are critical to our analysis.

Sometimes these concepts are used interchangeably by social scientists and common people alike as Francisco Gil-White explains in his paper titled: “The Study of Ethnicity and Nationalism Needs Better Categories: Clearing up the Confusions that Result From

Blurring Analytic and Lay Concepts.”5 Here the author tries to shed some light on the confusion that exists within the academic community when defining concepts relating to ethnicity and nationalism while making an effort to create better categories. Needless to say, when such confusion exists between academics, the tendency of common people to descend into even more confusion is quite understandable. Gil-White in turn coins the term “ethnie” instead of the more largely used “ethnic group” and argues that it must fulfill three elements in order to be called such. An ethnie must have: (1) An ideology of membership by descent, (2) The perception of a unique and homogenous culture (typically, associated with a particular territory), (3) Category-based normative endogamy.6 Therefore he defines an ethnie as “a collection of people who, at a minimum, represent themselves as a self-sufficiently and vertically reproducing historical unit implying cultural peoplehood.”7The author makes a plausible definition of ethnicity, while drawing from a considerable pool of statements by other nationalism scholars which resemble his definition.8

One can anticipate that other scholars partly disagree. Walker Connor for example is in the same mind when he notes that the terms nation and nationalism have a slipshod use and this constitutes a rule rather than an exception. However he also tries to define the nation by saying that it, “…connotes a group of people who believe they are ancestrally related.” And that “Nationalism connotes identification with and loyalty to one’s nation as just defined. It doesn’t refer to loyalty to one’s country.”9

Philip Spencer and Howard Wollman again assert the difficulty in defining these concepts and express that: “…the central focus of nationalist attention and energy, the nation, is a slippery and elusive object.”10

What can be understood from the examples given above, by different scholars of nationalism, is that there is no universal definition or agreement in how to define these concepts but rather strong similarities and few substantial contradictions. The term nationalism is perhaps less debated and is defined by all in nearly the same way i.e. the idea or action to transform or keep the nation or ethnic group into a political formation like the state.11 Despite the disagreements on the “nation,” we are obliged to choose and use this concept much like the authors who view it as useful and define it similarly to each-other. This is because the term is quite beneficial for analytical purposes but also because we need a term for societies which are multiethnic and simultaneously a nation. For example in USA people consider themselves a nation even though they are racially, and ethnically different, the same applies arguably to many other countries like Belgium, Afghanistan, South Africa, India, Switzerland, etc. where the nation as a characteristic and part of identity is above the ethnic or racial or linguistic identity. Smith and Grosby among others assert exactly this.12

Another reason for our choice is that the academic debate is not of a primary concern. What is indeed important is how people in general, and the people of the Western Balkans (WB) in particular, view the nation. They believe and think that the nation is as real as it can be, as Walker Connor notes, “…it is not what is, but what people believe is that has behavioral consequences.”13 Furthermore a social construction, like the nation, is not perceived as such; on the contrary as Alexander Motyl explains, people are not conscious that they construct these realities, they are not conscious that they engage in social construction and as a result they take for granted a socially constructed reality.14 It is real to the people in the WB, since we are interested in how these perceptions of the ‘self’ as an ethnic group and nation (i.e. Serbs, Albanians, Macedonians, Bosnians, and Croatians) impacts security in the region. We are obliged to use concepts of ethnicity and nationality in much the same way.

At this point it is important to explain that beside ethnicity and nationality the term ‘ethno-nationality’ will be used. This is largely due to perceptions that the people of Kosovo and Macedonia have about these concepts, for them the ethnic group is also the nation. However, in the case of Kosovo and Macedonia (like in many other parts of the world) it is a reality that ethnicity and nationality overlap extensively.

Before this relationship is viewed, some light shall be shed on the concepts of “security” and “ethno-national conflict.” Security in this paper is meant in the traditional way i.e. it has at its center the traditional level where the focus is on the international and national/domestic level as opposed to the nontraditional level where the focus is on the individual. The paper uses the term specifically to portray state or national security, regional security (like in Kosovo and Macedonia) and the implications that a breach of it may have on neighbors and the wider geographical scale.15

For the other very important concept, namely “ethno-national conflict” this paper acquires the definition that Stefan Wolff so eloquently employs. He defines an ethno-national conflict as one in which the goals of at least one party to the conflict are defined in (exclusively) ethno-national terms, and in which the primary fault line of confrontation is one of ethno-national distinctions. Thus, ethno-national conflicts are a form of group conflict in which one of the parties involved interprets the conflict, its causes, and potential remedies along an actually existing or perceived discriminating ethno-national divide.

Having an understanding of the concepts presented above clears the way to pursue and fathom the relation between ethno-nationality and security. Wolf comes once again to our help when he notes, “Ethno-national conflicts are among the most intractable, violent, and destructive forms of conflict that society, states, and the international community have experienced and continue to face.”16 On the contrary ideological intrastate wars seem to be less so precisely because loyalties are less passionate and rigid compared to conflicts or wars with an ethnic background.17 Ethno-national conflicts are not only very violent but they are also more frequent. Since the Cold War ended to the mid-1990s, more than fifty ethnic conflicts have been fought around the world, out of which thirteen have caused more than 100,000 deaths each.18 One such conflict that quickly springs to mind is the ethnic conflict in Rwanda between Hutus and Tutsis where in a very short time period of three and a half months (April-July 1994) an estimated 500,000-800,000 Tutsis were murdered.19 The numbers speak for themselves; they leave no doubt that ethno-national conflicts are a grave concern for security.

A monument showing the names of the Albanian victims killed during the Kosova War in the village of Izbica. | AFP PHOTO / ARMEND NIMANI

A monument showing the names of the Albanian victims killed during the Kosova War in the village of Izbica. | AFP PHOTO / ARMEND NIMANI

This clearly states that violent ethno-national conflicts are more probable in multiethnic communities or when the boundaries of the state, ethnicity and the nation do not match. Now that we can view clearly the relation between ethno-nationality and security we shall proceed in the next section with the relation between ethno-nationality and the Western Balkans (especially, Kosovo and Macedonia).

It is true as Oberschall says that “religion or ethnicity are very real social facts, but in ordinary times they are only one of several roles and identities that matter.”20 However the role that ethno-nationality has on the identity of the people in the WB compared to other identities is in general more dominant and, as the 1990s war demonstrated, even determinant. Furthermore the 1990s war left scars and other security threats through-out the whole region. It is for this reason that this relationship has major importance for the case studies in this paper.

The concern here relates to security and the role that these identity perceptions play on security. In the case of Kosovo and Macedonia more, the strong role that these identity perceptions played on security in the past, and the fact that they still do to some extent today, makes the question off the role of identity perceptions in the security of these two countries so relevant. It is well known that both Kosovo and Macedonia have a complex ethnic structure and so accordingly they have security problems. In this context, the paper’s hypothesis is “identity perceptions based on ethnicity and nationality have an important role in security.” Correspondingly, “The effect of identity perceptions on security, on the basis of ethnicity and nationality” is the independent variable of the study. Conversely; “the security of Kosovo and Macedonia” is the dependent variable of the study. In the study the main questions are: “What are the effects of identity perceptions in the establishment of ethnicity and nationality?”, “What is the relation between identity and security?” And “How does the ethno-nationality affect the security of a region?”

So it must be stated that heterogeneity per se, even though it increases the probabilities for violent conflict, does not denote an automatic prediction for civil war

With regards to the theoretical framework of the study, a constructivist approach is used with a focus on theories of identity, more specifically the “social identity theory.” The research has aimed to explore how identity perceptions affect security thus providing for an identity based explanation to security issues.

Constructivism is indeed a useful approach because it asserts that knowledge is filtered through the theories that we choose and not that the world simply is waiting to be discovered by applying empirical research. Friedrich Kartochwil states: “the social world is of our making, and it requires an episteme that takes the questions of our world-making seriously and does not impede an inquiry on the basis of a dogmatic conception of science or method.”21

Social identity theory (SIT) explains Hogg, analyses “the role of self-conception in group membership, group processes, and intergroup relations.”22 The SIT defines the social identity as the individual’s knowledge that she or he is part of a social category or group.23 Hence, we are to understand that this theory analyses the role of an individual’s identity as a group member on group processes and intergroup relations. This theoretical approach is particularly useful for this research since we will analyze the role of ethno-nationality on security by looking at intergroup relations. For example how does perceiving one’s self as Albanian or Serb affect these intergroup relations in terms of security; i.e. why perceiving each-other and themselves in a negative light has resulted in devastating war and ethnic cleansing.

According to SIT, people tend to classify themselves as well as others into diverse social categories and these categories are prototypical characteristics which are abstracted by the group members.24 Therefore a social group is a set of persons who share a common social identity or see themselves as part of the same social category; the SIT defines the group in these terms i.e. the individual’s’ self-conception as a group member.25 This social classification or social categorization serves two main functions. On one hand it places order in the social environment by providing individuals with the means to systematically define others, and on the other hand, the individual him/herself is bestowed with the characteristics of the category or group to which he/she belongs.26

The Complex Ethnic Structure of Kosovo and Macedonia

There is little doubt that the countries of Kosovo and Macedonia are in a complex region burdened by many problems, which spilled-over to serious effect in the 1990s. It is essential to understand this complexity in order to analyze their security; therefore in this part of the paper, some light will be shed on the regions’ composition.

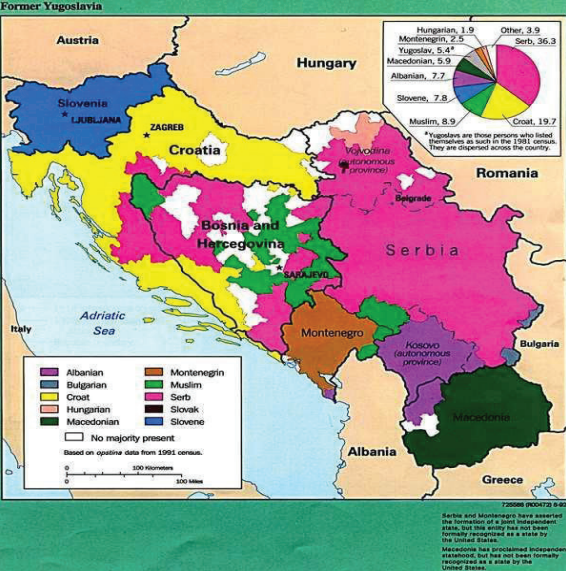

The Western Balkans map (map 1), demonstrates complexity of this region. Heterogeneity does seem to increase substantially the probabilities of a violent conflict breaking out. Even so it must be stated that heterogeneity per se, even though it increases the probabilities for violent conflict, does not denote an automatic prediction for civil war. Another factor that contributes largely to incentives for ethnic conflict in a heterogeneous state is the territorialization of ethnic groups. As we can see, ethnicities in countries such as Bosnia and Herzegovina (BiH), Kosovo and Macedonia are territorialized, thus providing incentives for security problems. It is no coincidence that we have security problems precisely in these three countries in the WB and not in the others. As Wolff suggests:

Bosnia, Macedonia, and Kosovo remain inextricably linked as three cases in the Western Balkans that, despite superficial stability in the former two, and an apparent “solution” of the latter, represent unresolved self-determination conflicts which all have significant potential to contribute to further regional instability.27

Map 1: Ethnic Distribution in the Western Balkans, 2008

Kosovo and Macedonia are the two cases which will be discussed in this paper. Both countries are inhabited by large numbers of Albanians; in the former they constitute a majority while in the later they constitute a significant minority. Interestingly Albanians were considered a minority in Yugoslavia even though they were present in greater numbers than Montenegrins, Slovenes or Macedonians. They have a completely distinct identity from the other peoples inhabiting the Balkans. They speak an Indo-European language which has its own unique branch that is not similar to any other language. Remarkably, it is language that has defined the identity of Albanians, i.e. the Albanian language is what makes an Albanian distinct in contrast to the other Balkans people where religion has primarily defined them as nations.29

Religion contrary to the other Balkans people is not a distinctive contributing factor in Albanians ethnic identity perception.30 This stems from the fact that they belong to many religions i.e. they are predominantly Muslims (Sunni and the Sufi Bektashi sect.), but with considerable numbers of Christians (Orthodox and Catholic) and Atheists.31

Albanians of the Former Yugoslavia are found, as the map shows, mostly in Kosovo and Macedonia while a small fraction of them lives in Serbia and Montenegro. While Montenegro does not have an ethno-national problem, at least not enough to be a security concern for the region, Kosovo and Macedonia unfortunately do. Kosovo seems to be the most problematic states after Bosnia. Even though ethno-nationalities are not as entangled as in Bosnia, the legacy of the war and disputes over status makes it a country with security problems, especially in its northern territory. It is no coincidence that the territoriality of the Serbs there poses a security problem, confirming the claim that territoriality of ethno-nationality increases the chances of ethnic conflict.

It can be argued that the same applied to Albanians in general in Serbia before the war that led to the independence of Kosovo. Namely, the territoriality of Albanians in Serbia, the fact that they were in a majority in the province of Kosovo and had continuity with each-other and Albania were major incentives that led to an ethno-national conflict between Serbs and Albanians. A conflict that shook the security of the region and beyond.32 These reasons and of course the extensive different identity perceptions between the belligerents led ultimately to the situation we have today. Hence the relation between identity perception and security on Kosovo will be deeply scrutinized in the chapter on Kosovo.

Macedonia presents a somewhat more relaxed security problem based on similar principles as the other cases mentioned, i.e. on different identity perceptions or ethno-nationalities. The disputes there arise between ethnic Albanians and Macedonians, with divisions between them as significant as the ones between Albanians and Serbs. They too are quite different in cultural, ethnicity, language and religious terms. Macedonians are a south Slavic people, predominantly orthodox and have their own language similar to Bulgarian.33 These differences unfortunately are quite often perceived as reciprocal threats to each community and lead to security concerns.

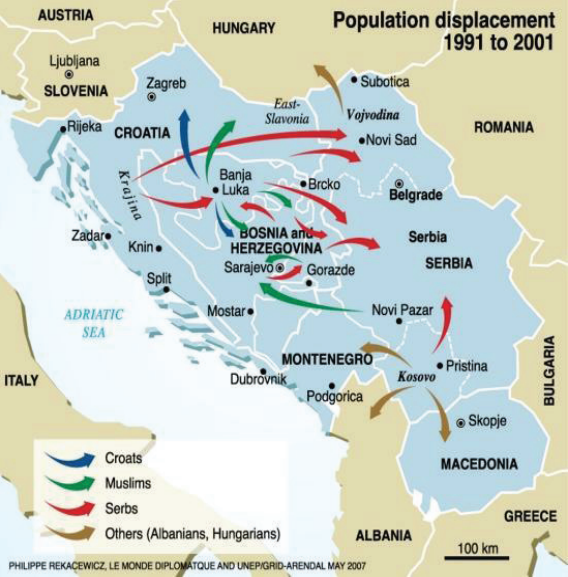

The distribution of different groups changed considerably with the Yugoslav wars. Map 2 (Yugoslavia Ethnic Composition before the War) and Map 3 (Population Displacements) show that ethno-national borders used to be quite different, especially in Croatia where few Serbs remain nowadays. A simple comparison between ethno-nationalities before the war and after it (Maps 2 and 1 respectively) helps in understanding the role of identity perception on security and as a consequence on peoples’ lives.

Map 2: Yugoslavia Ethnic Composition before the War

Source: CIA

Map 3: Population Displacements

Case Analysis: Kosovo

Kosovo plays an important part in the security puzzle of the Western Balkans. Without doubt the conflict in Kosovo was the last chapter of the Yugoslavian breakup, even though unfortunately it’s a chapter not yet fully closed. If the security situation in Kosovo were to deteriorate it would have significant repercussions within the region as a whole and beyond; thus it is important that this security issue be analyzed.

In Kosovo as in the rest of the Western Balkans, we have an ethno-national security problem i.e. the security issues that we have today stem from ethno-national differences. These differences can be real, perceived or constructed but nonetheless part of identity perceptions. Therefore in order to find the role of identity perceptions on the security of Kosovo we must trace the process of identity creation in history i.e. how were these identities created and why they result in such animosity between these groups.

As mentioned previously an important and special relationship exists between the nation and territory. In the case of Serbs and Albanians this is crucial to explain the role that the relationship between these two peoples and the territory of Kosovo plays on their identity and therefore on security. However, to explain it we should take a brief look at the history which plays a major role in peoples’ minds. Before Kosovo became a country, a province of Serbia and or any of its other administered forms, it used to be in antiquity a region inhabited by a people called Illyrians.36 Since medieval times it has been inhabited by Albanians and Serbs, both of whom have strong connections to the land and see it as historically and rightfully theirs.37

For long there has been a debate between Albanian and Serbian academia, and as a result people in general, as to who inhabited Kosovo first. This is perceived by both parties, among other things, as rights over the land. The Serbs refer to their medieval times and cultural heritage to state that they were always there and to prove continuity. On the other hand Albanian academia supports the theory that Albanians are descendant of Illyrians. They argue that, since Illyrians or more specifically Dardanians (an Illyrian tribe) inhabited the western part of the Balkan Peninsula including Dardania (roughly todays Kosovo) they were there first, before the arrival of Slavic people, including the Serbs, in the 6th-7th century CE.38 Both parties claim to have been in Kosovo before the other arrived.

EU and American policy is trying to create a new identity in Kosovo i.e. the “Kosovar’’ nation –which would be above ethnic identities– as the means to keep Kosovo together

Alongside the debate of who inhabited Kosovo first there is also the debate of who was in a majority in the land and what this represents in terms of culture. The Serbs refer to Kosovo as the heart of Serbia itself, and therefore of the Serbs. They usually start their references from the glorious medieval times in the 12th century with the reign of Stefan Nemanja and later his son Sava which secured the autonomy of the Serbian Orthodox church and began the tradition of building churches and monasteries. Sava is considered to be the founder of Serbian statehood and national identity.

However, negative identity perceptions between these two peoples did not begin until the nationalistic era in the second half of the 19th century. Once they began, they were extreme and remain marked in the memories of both parties as a collective suffering.

Looking at Serb and Yugoslav Albanian relations in the past one hundred years, or since the incorporation of Kosovo into Yugoslavia, this becomes evident. The Balkans wars in the beginning of the 20th century brought much suffering and an increased nationalist feeling. In this period Serbs, Montenegrins, Bulgarians and Greeks were fighting against the Ottomans. Albanians, who fought the Ottomans too in order to create their independent state, found themselves threatened by their neighbor’s success, since the territories the latter wanted although under Ottoman administration were largely inhabited by Albanians.

A Possible Solution Based on Identity Perception’s Role on Security

Three solutions are conceivable for Kosovo, all focused on the north. Namely the Ahtisaari plan, stronger autonomy for the north and a land swap.39 The EU and USA have opted so far for the first, i.e. preserving Kosovo’s “territorial integrity” and creating a functional multinational democracy. To achieve it they have adopted an open-end talk strategy between Pristina and Belgrade.40 But this strategy has led to a stalemate; the Ahtisaari plan is not being implemented in the north and it hasn’t produced more international recognition. Moreover Serbia seems to strengthen its position while diverging from a reconciliatory path. Former ultra-nationalist Tomislav Nicolić was elected president in May 2012, while a nationalist government was erected under the direction of Ivica Daĉić (also called ‘’little Sloba” as in Slobodan Milošević).41 Serbia continues to block Kosovo’s further international recognition while controlling its Northern region and undermining its’ sovereignty. These facts and EU policies which continue to support Serbia’s’ EU accession seem to contribute to a dangerous status quo. In the beginning of 2012 Serbia was granted EU candidate status42 and quite recently the enlargement commissioner Štefan Füle declared that recognition of Kosovo is not a condition for Serbia’s EU integration.43 EU and USA policy seems flawed because Kosovo’s problems can’t be solved unless there is a political agreement with Serbia.

EU and American policy is instead trying to create a new identity in Kosovo i.e. the “Kosovar’’ nation –which would be above ethnic identities–44 as the means to keep Kosovo together. Although good on paper that is quite a dangerous gamble when one considers previous failures of such efforts in Yugoslavia.45 In a region where nationalism is this strong, such a process will hardly be allowed. Moreover, for it to promote peace it has to be embraced by all its nationalities but as the considerable majority of Kosovo is ethnic Albanian the minorities will naturally continue to strongly identify themselves with their ethnic group.

Recognizing Kosovo’s independence without anything in return would be political suicide thus no politician will opt for it in Serbia. Kosovo will not become a UN member without Serbian recognition, making a deadlock inevitable. But as we mentioned above there are repercussions to the status quo and the possible frozen conflict. This strongly hinders reconciliation between Serbs and Kosovo Albanians because the former will be regarded by the latter as a continuous threat to their new established independence.

Ethno-national conflicts can be prevented and security stabilized if people do not perceive others as threats or enemies to their own identity and culture but instead as partners

The second solution, -i.e. stronger northern autonomy- although more viable is rejected by Kosovo Albanians and Serbs alike.46 Northern Serbs reject it on the grounds that they gain nothing from it since they already rule themselves, in fact they view it as a loss and Serbia simply accepts nothing less than to include northern Kosovo in its own territory for good.47 For Albanians on the other hand the Ahtisari plan was a hard pill to swallow because Kosovo Albanians had to give large concessions to the minorities, for example being classified as a multinational state while constituting roughly 92 percent of the population.48 The discrepancies with other countries are obvious. Serbia for example without Kosovo has only 82.9 percent Serbs,49 yet is not considered a multinational country. In addition Kosovo’s sovereignty is crippled because Serbia controls the north de facto while the constitution of Kosovo forbids it from joining another country, such as Albania, which according to a Gallup poll in 2010 is supported by 82 percent of the population.50

Hence the third solution, namely the territorial swap, seems the most viable and is largely based on constructivism. This solution seems the only one which can neutralize the long standing and strong negative identity perception of the “other”, thus promoting security. It is much easier if the parties, i.e. Albanians and Serbs instead of adopting new identities alter their negative perception of each-other to at least neutral ones or to construct new perceptions. Ethno-national conflicts can be prevented and security stabilized if people do not perceive others as threats or enemies to their own identity and culture but instead as partners.

The territorial swap or a ‘’border adjustment’’51 between Kosovo and Serbia is supported by some prominent individuals such as the former coordinator of the Stability Pact for South Eastern Europe, Erhard Busek, international relations professor John Mearsheimer and, US Congressman Dahna Rohrabacker.52 This is a solution rejected continually by the international community, arguing that it would open up a Pandora’s Box of border disputes worldwide.

The argument that you would establish a precedence is faulty not least because successful secessionist movements have existed worldwide before and will surely continue to exist after. If indeed a territorial swap would be a global precedent then unilateral secessions should have been far more influential to date. We have seen recognition of unilateral secessions of Slovenia, Croatia, Bosnia, Macedonia, and most recently Kosovo, which should have therefore given fuel to other secessionist movements; Pandora’s Box would have already been opened. Needless to say, remaining minorities in both countries must have all the constitutional rights, such as education in their own language and assured institutional representation.

Macedonia

Macedonia did not experience a violent secession from Yugoslavia/Serbia and wide scale interethnic conflict has been avoided somewhat successfully compared to Croatia, Bosnia or Kosovo. However, the country has not been immune to interethnic conflict.53 In the 90s, following its declaration of independence, tension mounted between the two largest national groups erupting in 2001. However, thanks to the intervention of the international community and lack of real will from the parties, wide scale civil war was stopped in its tracks.54 This is generally considered a success when compared to the other regional conflicts. The conflict had a rather limited number of casualties; there were some 1000 dead compared to the 100,000 in Bosnia, 20,000 in Croatia and 10,000 in Kosovo.55 Although, it must be noted that success here is defined in a rather normative fashion.

As elsewhere in the region, the 2001 conflict stemmed from a complex process of identity construction, biased interpretations of historical events and prejudicial identity perceptions of the other. Despite notable improvements, Macedonia remains a problematic country with security problems worthy of attention.56 2012 saw tension rise again between Slavic Macedonians57 and Macedonian Albanians and they are considered the worst since the 2001 conflict,58 thus to avoid a possible repetition of security problems, care is needed. Either way these security problems in Macedonia are not confined to negative perceptions between Macedonians and Albanians but rather are intertwined with the historical process of a distinct Macedonian identity construction and its strained relations vis-á-vis the neighbors. Thus before analyzing identity perceptions between Macedonians and Albanians and their impact on security processes, tracing shall be used to find the causalities of the problematic formation process of a distinct Macedonian identity. This process and its interpretations on the other hand have major repercussions on security. In return security perceived threats as well as security breaches –such as the 2001 conflict- influence Macedonian-Albanian relations directly. The so called “Macedonian Question” comprises these conglomerate complexity of: identity construction problems, identity perceptions and security; hence the next section will proceed in its analysis.

The Macedonian Question: Consequences on Identity Perceptions and Security

The Macedonian Question refers to two main issues: (1) The origins and identity of the Slavic Macedonians and (2) Territorial claims over “Geographical Macedonia.” We have already mentioned that today Macedonians are a Slavic people who belong primarily to the orthodox faith. However a distinct Macedonian identity is questioned and challenged primarily by Bulgaria and Greece and to some extent Serbia. On the other hand, Geographical Macedonia, which comprises Vardar Macedonia or Former Yugoslavia Republic of Macedonia (FYROM); Pirin Macedonia or Bulgarian Macedonia and Aegean Macedonia or Greek Macedonia (See Map 4, below)59 is claimed by Macedonians, Bulgarians, and Greek extreme nationalists. Both issues have affected and continue to affect the construction of a distinct Macedonian identity and their perceptions which as a result has implications on security.

Map 4: Geographical Macedonia

Source: Victor Roudometof

As explained earlier, questions of identity are quite difficult since identities are social constructions and moreover products of a process which does not necessarily reflect historical accuracy but rather a somewhat subjective interpretation of historical events. Though hardly unique to the Balkans, it shows the constructivist process and what SIT has pointed out i.e. that group members tend to be positively biased towards their own and prejudicial of the “others.”

Both perceive the other as the problem and both feel they are victims. Albanians view with suspicion and do not justify Macedonians keen emphasis of their identity while the latter don’t regard most Albanians claims as legitimate

We have also noted that, people in general are not aware that they themselves engage in social constructions and tend to project the current perceptions of identity into the past. To be more explicit, in the people of the Western Balkans (WB) in general view their ancestors through today’s lenses i.e. they think that their ancestors had the same idea of unity and perception of the group similar to those found today.60

Either way, nationalism emerged in the 19th century; although ethnicities existed before, they did not have a prime role in social identity. In the WB, people do not make a clear distinction between the ethnic group and nation, thus continuity seems quite plausible to them. Acknowledgement of cultural or ethnic evolution is more realistic than current perceptions of the group unity as a nation. However, as mentioned previously, it is not “what is” that matters, but “what people believe is” that has behavioral consequences and in the Balkans what people believe affects their perceptions of the self and others. These perceptions however conflict with one another and as a consequence regional security is compromised.

What is stated above is crucial to understand why the Macedonian identity is a contested issue today and why it impacts so fervently on identity perceptions and security.

Macedonian - Albanian Relations: Implications on Identity Perceptions and Security

According to the 2002 census Macedonia has: 64.2 percent Macedonians, 25.2 percent Albanians and 10.6 percent others.61 Macedonian Albanians are a majority in the northwest and west of the country and can theoretically breakup it up along ethnic lines or at least descend it in to civil war. However, despite empty rhetoric, this is hardly their wish or aim. Nonetheless, Macedonians naturally fear such a scenario and as a result it greatly influences Macedonian perceptions of Albanians. Albanians on the other hand regard Macedonians as an oppressing majority which impedes their cultural and language rights. Even though numbers suggest that Macedonia is a multiethnic state, Macedonians consider it their nation-state where Albanians are merely a minority. Both perceive the other as the problem and both feel they are victims. Albanians view with suspicion and do not justify Macedonians keen emphasis of their identity while the latter don’t regard most Albanians claims as legitimate. Again, an ethnocentric view of history and negative identity perceptions as SIT points out impedes substantial progress and leaves a vulnerable security environment. This process of a vicious circle of negative identity perceptions led to the 2001 conflict and to security threats today.

High representatives from Albania, Kosova and Macedonia attending the centennial celebration for the independence of Albania in 2012. | AA PHOTO / MURTEZA SULOOCA

High representatives from Albania, Kosova and Macedonia attending the centennial celebration for the independence of Albania in 2012. | AA PHOTO / MURTEZA SULOOCA

The fragile relationship between Macedonians and Albanians is naturally subject to Macedonians security fears and negative perceptions that result from a contested identity because these fears and negative perceptions are projected towards Macedonian Albanians as well.62 Studies have shown that both parties, if little else, agree on two things: NATO membership and EU integration. Both organizations are seen as guarantees of preserving Macedonian statehood and security from outside as well as domestic threats.63 Prospect NATO and EU membership relaxes Macedonians as well as Albanians security and socio-economic concerns while it guarantees cultural and human rights for the latter. EU membership is also seen specifically as a road map to much desired economic improvement having as an example Romania and Bulgaria.64 Hence, the fact that both processes are blocked by Greece has led the country into a dangerous stalemate. The 2012 increased tensions stem partially from this frustrating deadlock, which is why solving the dispute over the country’s name with Greece would help a great deal in the improvement of Macedonia – Albanian relations and perceptions, as well as security.

After Macedonian independence, relations deteriorated. Ragaru argues that an unsecured Macedonian majority, due to external as well as internal threats, engaged in ambitious nation-state building emphasizing the Macedonian-nesss of the state.65They felt threatened externally because Bulgaria, Greece and Serbia did not recognize a distinct Macedonian nation and state recognition proceeded rather slowly. They felt threatened internally because Albanians boycotted the independence referendum and later in 1992 opted for autonomy within Macedonia; hence Albanians were not viewed as loyal subjects of the new state.66 Albanians feared that independence meant division from Kosovo Albanians, which indeed created much difficulty for them due to strong cultural, economic and family connections.

The events of the 90’s greatly increased negative perceptions between the parties and added to existing animosities which would later result in war. Arens argues that if both parties had been more cautious, if Macedonians had tried to make a historical agreement with Albanians and not alienate them from the republic and if Albanians hadn’t been unreasonable and not made exaggerated claims about their numbers, perhaps today we wouldn’t have security problems.67 The international community made some efforts to resolve interethnic issues in the 90’s but the Macedonians dragged their feet and both parties moved further apart towards the arms of nationalism.

A Possible Solution to Improve Identity Perceptions and Security

The primary challenge rests upon negative identity perceptions between Macedonians and Albanians. To improve these relations and perceptions it would be best if some external issues impacting them be solved first.

Macedonians indeed face tough issues ahead, but stalemate is worse than compromise. Between all possible solutions from: (1) division, (2) autonomy for Albanian region, (3) a dual ethnic state, (4) a civic state and (5) a Macedonian ethnic state,68the fourth option seems the most appropriate to reduce negative perceptions, keeping the country united and avoiding security problems. However, firstly the name dispute with Greece should be resolved. The International Crisis Group (ICG) has more than once made recommendations towards this goal. Macedonia and Greece should achieve a pragmatic agreement to the benefit of both countries. Macedonians, ICG argues should retreat from provocations such as naming its international airport “Alexander“ the Great” and similar such controversial ancient identity claims and commemorations. They should accept a regional definition of the country’s name similar to the UN mediator proposal: “Republic of North Macedonia” instead of a national connotation.69 Greece on the other hand should accept a Macedonian identity, language and nation with that name (or perhaps Makedonians in Macedonian language) as well as assurances from Skopje that their name has no exclusivity or territorial claims.70 By solving the name deadlock NATO membership and EU integration process will follow, thus making both Macedonians and Albanians happy that their country is moving forward. At least this will decrease tensions in the region and Macedonians will feel more secure with their identity unchallenged.

Due to its ethnic composition Macedonia is a de facto multiethnic state and this should be cherished as an asset, as in the example of Switzerland. A civic unitary state as opposed to other options would satisfy Albanians as well as Macedonians in the long run. Albanians wouldn’t be second class citizens and Macedonians would preserve territorial integrity as well as security intact. If Albanians are viewed as partners rather than a threat then building a tolerant state should be easier, therefore it is up to Macedonian and Albanian politicians to stop exploiting ethnic based issues for gaining votes and popularity.

Concluding Remarks

This thesis has tried to provide an identity based explanation to security problems. It has tried to show that reasons behind conflicts often stem from how people identify themselves and others i.e. the fact that we divide ourselves into ‘us’‘ and ‘them’ has behavioral consequences which can lead to armed conflict. The constructivist theoretical framework helped us emphasize and explain the constructive nature of these social identities as well as their abstract dimension. More explicitly constructivism showed how ethnicity and nationality are actually social constructions which often prevail over many other forms of social identification. This is quite important when we consider that people involved in armed conflicts generally have a primordial understanding of identity and are not aware that they engage in social constructions. This theoretical approach is also complementary to other more main stream security studies based on power, interests, etc.

Our two case studies chosen for analysis, namely Kosovo and Macedonia, explicitly show how important identity perceptions are in security issues. Both countries suffered from armed conflict due to negative identity perceptions between their different ethno-national groups. Through process tracing, it has been discovered how these people have constructed their different social identities and how historical events have shaped these identities and perceptions of themselves as well as their competing groups. However, the analysis of the case studies suggests that, though historical events have constructed different social identities and their according intergroup perceptions, it is the ethnocentric interpretation of these historical events that plays a major role in identity perceptions. In fact, biased interpretations, where people often believe themselves as victims of the ‘rival’ social group, have induced fear and belief of threat. Accordingly these negative perceptions have pushed for more aggressive stances and justifications of violent acts in the belief that protection comes only by correcting historical ‘wrongs’ and from the arms of their respective social group. Simply put, people taking part in these conflicts believe that the others are to blame for past suffering and they constitute a threat to their protection, hence violence towards them is justified.

To solve security problems in short amount of time we should take specific steps for specific cases and eliminate the immediate causes which induce negative identity perceptions

Unfortunately, these beliefs and negative identity perceptions have at times materialized into actions leading to security problems. Similarly it has been found that this resembles a vicious circle where negative perceptions of others lead to conflict and conflict itself leads to more negative identity perceptions. Indeed, the analysis suggests that the Yugoslavian breakup and the ensuing wars stemmed from negative identity perceptions but also that these wars as a result induced even more negative identity perceptions. The case studies also show that not everyone is equally aggressive and willing for conflict. This does not necessarily mean that one group is ‘worse’ than others but that other factors have influenced them more. The level of ethnocentric interpretations and propaganda, level of manipulation by elites and more importantly the power or ability to create conflict with the belief that it will benefit their group is greater amongst those who escalate violence. It is no coincidence that social identity theory has been chosen as a more specific guiding tool. SIT indeed explains this natural tendency of ours to identify or categorize ourselves and others in social groups. More importantly it shows that we do attribute virtues and vices in rather simplistic and biased manners. Simply put, people have the tendency to view members of their own group in a better light and be prejudicial vis-à-vis others and this has behavioral consequences on intergroup relations. In fact the two cases fit perfectly with explanations given by SIT, since analysis showed that all ethno-national groups studied are prone to these biases. However, different identity perceptions are not a problem in themselves; in fact they are quite normal, largely present and more importantly inevitable. It is only when they are negative to the extent that group members are willing to do harm to others that security becomes a concern. For example there is nothing wrong with a Swedish person perceiving oneself as such, but it becomes a problem if more members think of others as a threat, based solely on simplistic and prejudicial differences. Similarly, the case studies chosen suggest that it is not the differences per se that threaten security but rather the negative perceptions of other groups and the desire to dominate over that group that have led to conflict. Unfortunately, in these cases people disregard all other shared similarities and focus on differences and stereotypes. The analysis shows that disregard or misconceptions of identity perceptions by other actors such as the International Community is not only deemed unwise but it can indeed lead to a great deal of human suffering.

This paper has pointed to the need for more attention towards identity perception’s effect on security. This issue must be taken into account when crafting policies for long term security solutions. Although it appears that no easy or universal solution exists we propose a paradigm which we suggest that, in the long term, will relax security threats based on negative identity perceptions. The road forward lies in placing the emphasis on shared similarities; objective, unbiased and proper teaching of history; explaining the construction of social identities; avoiding media stereotypes, propaganda and political nationalistic rhetoric. However these changes require a considerable amount of time, perhaps even generations while some security issues are more pressing than others. It is also somewhat naive to think that people will refrain from the destructive behaviors mentioned above, especially when benefits can be gained for the protagonists.

Hence, to solve security problems in short amount of time we should take specific steps for specific cases and eliminate the immediate causes which induce negative identity perceptions. The solutions presented for each case throughout this paper explore exactly this option. Indeed, specific solutions must be strongly correlated to identity perceptions and whatever the solution the aim should be to improve identity perceptions as the means to avert security problems. Briefly, it can be said that the paper’s hypothesis has been justified. By finding the immediate and major causes of negative identity perceptions and by working to correct them we can hopefully improve security in the short term and gain time in order to devise better policies in the future. Identity perceptions will improve in the long run if we constantly try to emphasize the abstractness and relativity of identities, or the fact that they are subject to change and have always been so. The removal of negative identity perceptions will ultimately improve security for all.

Endnotes

- Steven Grosby, Nationalism: A very short introduction, (Great Britain: Oxford University Press, 2005), p. 12.

- Ibid. p. 10-11.

- Tayyar Arı, Uluslararası İlişkilerde Postmodern Analizler-1 Kimlik Kültür Güvenlik ve Dış Politika, (Bursa: Marmara Kitap Merkezi Yayınları, 2012), p. 33.

- Grosby, Op. Cit, p. 12.

- Francisco Gil-White, “The Study of Ethnicity and Nationalism Needs Better Categories: Clearing up the Confusions that Result from Blurring Analytic and Lay Concepts,” Journal of Bioeconomics, Vol. 7, No. 3 (2005), pp. 239-270, retrieved 17 May 2014 from http://www.hirhome.com/academic/categories.pdf.

- Ibid. pp. 7-8.

- Ibid., p. 8.

- Ibid. pp. 21-22.

- Walker Connor, Ethnonationalism: The Quest for Understanding, (USA: Princeton University Press, 1994), p. 11.

- Philip Spencer and Howard Wollman, Nationalism: A Critical Introduction, (Great Britain: SAGE, 2002), p. 2.

- Arı, Op. Cit. p. 35.

- Antony D. Smith, Nationalism, (2nd Edn), (Great Britain: Polity Press, 2010), pp. 10-18.

- Connor, Op. Cit., p. 75.

- Alexander J. Motyl, “The Social Construction of Social Construction: Implications for Theories of Nationalism and Identity Formation,” Nationalities Papers, Vol. 38, No. 1 (2010), pp. 59–71, retrieved 08 June 2014 from http://www. tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/00905990903394508#preview.

- Michael E. Smith, International Security: Politics, Policy, Prospects, (Great Britain: Palgrave Macmillan, 2010), pp. 11-15; 316-319; Keith Krause, “Towards a Practical Human Security Agenda,” DCAF Policy Papers, No. 26, (2006), pp. 4-7, retrieved 11 June 2014 from http://www.dcaf.ch/Publications/Towards-a-Practical-Human-Security-Agenda.

- Stefan Wolff, “Managing Ethno-National Conflict: Towards an Analytical Framework,” Commonwealth and Comparative Politics, Vol. 49, No. 2 (2011), p. 162.

- Brown Kaufman et al.; King, Snyder, Gurr and Harrif, cited in Michael E. Smith, Op. Cit. p. 100.

- Gurr, cited in Michael E. Smith, Ibid., p. 101.

- James Hughes, “Genocide and Ethnic Conflict” in Karl Cordell and Stefan Wolff (eds.), Routledge Handbook of Ethnic Conflict, (Abingdon: Routledge, 2010), p. 13.

- Anthony Oberschall, “The Manipulation of Ethnicity: From Ethnic Cooperation to Violence and War in Yugoslavia,” in Daniel Chiriot and Martin E. P. Seligman (eds.), Ethnopolitical Warfare: Causes, Consequences, and Possible Solutions, (Washington D.C.: American Psychological Association, 2001), p. 983.

- Friedrich Kratochwil, “Constructivism: What It Is (not) and How It Matters”, in D. Della Porta and M. Keating (eds.), Approaches and Methodologies in the Social Sciences, (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2008), p. 97.

- Michale A. Hogg, “Social Identity Theory,” in Peter J. Burke (eds.), Contemporary Social Psychological Theories, (USA: Stanford University Press, 2006), p. 111.

- Helin Ertem Sarı, “Kimlik ve Güvenlik İlişkisine Konstrüktivist Bir Yaklaşım: ‘Kimliğin Güvenliği’ ve ‘Güvenliğin Kimliği’,” Güvenlik Stratejileri, Vol. 8, No. 16 (2012), 177-216, p. 181.

- Blake E. Ashforth and Fred Mael, “Social Identity Theory and the Organization,” Academy of Management Review, Vol. 14, No. 1 (1989), p. 20, retrieved 10 June 2014 from http://www.jstor.org/stable/258189.

- Sibel A.Arkonaç, Gruplararası İlişkiler ve Sosyal Kimlik Teorisi, (Istanbul: Alfa Yayınları, 1999), p. 26.

- Ibid., pp. 26-27.

- Stefan Wolff, “Learning the Lessons of Ethnic Conflict Management? Conditional Recognition and International Administration in the Western Balkans since the 1990s,” Nationalities Papers, Vol. 36, No. 3 (2008), p. 554, retrieved 11 June 2014 from http://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/00905990802090223.

- The Library of Congress, Central Intelligence Agency, Washington, D.C., 2008, retrieved 22 June 2014 from http://hdl.loc.gov/loc. gmd/g6841e.ct002411.

- Tim Judah, Kosovo: What Everyone Needs to Know, (New York: Oxford University Press, 2008), pp. 9-10.

- Burak Tangör, Avrupa Güvenlik Yönetişimi Bosna, Kosova ve Makedonya Krizleri, (Istanbul: Seçkin Yayıncılık), p. 24.

- Judah, Kosovo: What Everyone Needs to Know, pp. 7-9.

- Tangör, Avrupa Güvenlik Yönetişimi Bosna, Kosova ve Makedonya Krizleri, p. 25.

- Bohdana Dimitrova, “Bosniak or Muslim? Dilema of One Nation with Two Names,” Southeast European Politics, Vol. 2, No. 2 (2001), pp. 96; 98, retrieved 16 July 2014 from http://www.seep.ceu.hu/issue22/dimitrovova.pdf. See also: Eniel Ninka, “Go West: The Western Balkans Toward European Integration,”,MPRA paper, No. 21459, (2010), p. 20, retrieved 16 July 2014 from http://www.seep.ceu.hu/issue22/ninka.pdf.

- Central Intelligence Agency, “Ethnic Groups in Yugoslavia,” Making the History of 1989, Item #170, retrieved 19 July 2014 from http://chnm.gmu.edu/1989/items/show/170.

- Philippe Rekacewicz, UNEP/GRID-Arendal, 2007, retrieved 19 July 2014 from http://www.grida.no/graphicslib/ detail/population-displacements-1991-to-2001_677f.

- Illyrians were an ancient people that inhabited roughly the Western Balkans since the first millennium B.C.E.

- Judah, Kosovo: What Everyone Needs to Know, Op. Cit., pp. 18-19.

- See: Skender Anamali, “The Illyrians and the Albanians”, in Kristaq Prifti et al. (eds.), The Truth on Kosova, (Tirana: Encyclopedia Publishing House, 1993), pp. 15-18; Eqerem Çabej, “The Problem of the Autochthony of Albanians in the Light of Place-Names,” in Kristaq Prifti et al. (eds.), The Truth on Kosova, pp. 19-23; Aleksander Stipcevic, “Every Story About the Balkans Begins With the Illyrians”, in Kristaq Prifti et al. (eds.), The Truth on Kosova, pp. 26-28.

- International Crisis Group, Kosovo and Serbia After the ICJ Opinion, Europe Briefing No: 206, (26 August 2010), p. 8, retrieved 19 July 2014 from http://www.crisisgroup.org/en/regions/europe/balkans/kosovo/206-kosovo-and-serbia-after-the icj-opinion.aspx.

- International Crisis Group, Kosovo and Serbia After the ICJ Opinion, pp. 6-8.

- Tomislav Nikolic Beats Boris Tadic in Serbia Run-off, BBC News, (21 May 2012), retrieved 19 July 2014 from www.bbc.co.uk /news/world-europe-18134955; Profile: Prime Minister Ivica Dacic of Serbia, BBC News, (27 July 2012), retrieved 19 July 2014 from http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-europe-19017144.

- European Commission: Enlargement, retrieved 19 July 2014 from http://ec.europa.eu/enlargement/countries/detailedcountry information/serbia/index_en.htm.

- EU: Serbia does not Have to Recognize Kosovo, Balkan Insight, (5 September 2012), retrieved 19 July 2014 from http://www.balkaninsight.com/en/article/eu-does-not-request-serbia-to-recognize-kosovo.

- Matteo Albertini, “Kosovo: An Identity Between Local and Global,” Ethnopolitics Papers, (15 February 2012), retrieved 22 July 2014 from http://www.ethnopolitics.org/ethnopolitics-papers/EPP015.pdf.

- In the Second Yugoslavia Tito made efforts to create a Yugoslav nation to prevail above all others and since 1971 it was one of the ethnicity choices in the census.

- International Crisis Group, Kosovo and Serbia After the ICJ Opinion, Op. Cit., pp. 11-12.

- International Crisis Group, Kosovo and Serbia After the ICJ Opinion, p. 11.

- Alice Engl and Benedikt Harzl, “The Inter-relationship between International and National Minority-Rights Law in Selected Western Balkan States,” Review of Central and East European Law, Vol. 34, No. 4 ( 2009), p. 310, retrieved 23 July 2014 from http://www.ingentaconnect.com/content/mnp/rela/2009/00000034/00000004/art00002; Constitution of the Republic of Kosovo, retrieved 24 July 2014 from http://www.kushtetutakosoves. info/repository/docs / Constitution.of.the.Republic.of.Kosovo.pdf.

- The World Factbook: Serbia, Central Intelligence Agency, retrieved 28 July 2014 from https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook/geos/ri.html.

- Gallup Balkan Monitor, “Insights and Perceptions: Voices of the Balkans, 2010 Summary of the Findings, Brussels, (2010), retrieved 24 May 2014 from http://www.balkan-monitor.eu/files/BalkanMonitor-2010_Summary_of_ Findings. pdf; See also: International Crisis Group, Pan-Albanianism How Big a Threat to Balkans Stability, Europe Report No: 153, (25 February 2004), retrieved 24 July 2014 from http://www.crisisgroup.org/en/regions/europe /balkans/albania/153-pan-albanianism-how-big-a-threat-to-balkan-stability.aspx; European Union Institute for Security Studies, Judy Batt (ed.), “Is there an Albanian Question?,” (January 2008), pp. 5-10, received 24 July 2014 from http://www.iss.europa.eu/publications/detail/article/is-there-an-albanian-question/.

- Border adjustment is a better term because Kosovo’s borders were redrawn in 1959 by attaching northern parts and removing Presevo Valley. See: Tim Judah, Kosovo: What everyone needs to know, Op. Cit., p. 5.

- See: “Kosovo Partition Would be “Best solution,” B92, (5 February 2012), retrieved 06 May 2014 from http://www.b92. net/eng/news/politics-article.php?yyyy=2012&mm=02&dd=05&nav_id=78634; John J. Mearsheimer, “The case for Partitioning Kosovo,” retrieved 17 June 2014 from http://mearsheimer. Uchicago.edu/pdfs/A0026.pdf; Dahna Rohrabacher, “A Balkan Peace Bargain,” The Wall Street Journal, (18 October 2011), retrieved 17 June 2014 from http://online.wsj.com/article/ SB10001424052970204479 5045766365328 83904782.html.

- Ömer Göksel İşyar and Ergin Ahmed, “Makedonya Cumhuriyeti’nde Arnavut Azınlık Sorunu,” Gazi Üni. İ.İ.B.F. Dergisi, Vol. 7, No. 3 (2005), pp. 217-239, p. 223.

- Lenard J. Cohen and John R. Lampe, Embracing Democracy in the Western Balkans, (USA: Woodrow Wilson Center Press, 2011), p. 64.

- Ibid., p. 68; Baskın Oran, Türk Dış Politikası Cilt II: 1980-2001, (Istanbul: İletişim Yayınları), p. 138; M. Necati Özfatura, “Makedonya’da İç Savaş,” Türkiye Gazetesi (15 June 2001).

- Cohen and Lampe, Embracing Democracy in the Western Balkans, pp. 364-365.

- Macedonian and Slavic Macedonian terms are used interchangeably unless otherwise indicated.

- See: A Dangerous Inter-Ethnic Balance in the Former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia, ELIAMEP, (June 2012), retrieved 22 June 2014 from http://www.eliamep.gr/wp-content/uploads/2012/07/New-BN1.pdf. (ELIAMEP is a Greek based think tank)

- Victor Roudometof, Collective Memory, National Identity, and Ethnic Conflict: Greece, Bulgaria, and the Macedonian Question, (USA: Praeger, 2002), p. 4.

- Aktan Hamza, Makedonya-Arnavutluk İlişkilerinde Arnavut Sorunu, (Skopje: Logos-A, 2006), p. 37.

- The World Factbook: Macedonia, Central Intelligence Agency, retrieved 10 July 2014 from https://www.cia.gov/library/ publications/ the-world-factbook/geos/mk.html.

- Jenny Engström, “The Power of Perception: The Impact of the Macedonian Question on Inter-Ethnic Relations in the Republic of Macedonia,” The Global Review of Ethnopolitics, Vol. 1, No. 3 (March 2002), pp. 11-13, retrieved 11 July 2014 from http://www.ethnopolitics.org/ethnopolitics/archive/volume_I/issue_3/engstrom.pdf.

- Stojan Slaveski, “Macedonian Strategic Culture and Institutional Choice: Integration or Isolation?”, Western Balkans Security Observer, No. 14, (July-September 2009), pp. 44-48, retrieved 11 July 2014 from http://kms2.isn.ethz.ch/ serviceengine/Files/ESDP/114831/ichaptersection_singledocument/251305f2-c18f-4343-bd3d-0668eed1b2e6 /en/Chap3.pdf.

- Ibid.

- Nadège Ragaru, “Macedonia between Ohrid and Brussels,” Chaillot Papers, No. 107 (January 2008), p. 5, retrieved 12 July 2014 from http://www.iss.europa.eu/uploads/media/cp107.pdf.

- Ibid. pp. 5-6.

- Geert-Hinrich Ahrens, Diplomacy on the Edge, (Maryland: The John Hopkins University Press, Woodrow Wilson Center Press, 2007), pp. 398-399.

- Ibid., pp. 401-403.

- International Crisis Group, Macedonia: Ten Years after the Conflict, Op. Cit., pp. 21-23.

- Ibid.