Introduction

This article examines the relationship between the State and religion in Great Britain. It begins by outlining Great Britain’s constitutional foundations and then sets the Church-State dynamic in the different regions of Great Britain within an historical context. Next it describes the current (and much changed) religious landscape and the various religious minority groups that are present in the country. Particular attention is paid to Muslims, who now comprise the largest religious group in Britain after Christians. The main features of contemporary law regarding religion are then outlined. A section on education follows, as this is a crucial issue in the British case, covering the ownership and management of schools, religious education itself, and the place of religious worship in the public educational system. The article then looks at chaplaincy in its different contexts, chaplaincy being a key site of state-religion engagement in Britain, which demonstrates both the continuity of the country’s Christian heritage and its gradual change to a multi-faith society. The growing non-religious constituency is an increasingly important feature in this mix. The concluding section reflects on the main debates and controversies surrounding religion in Great Britain. What emerges overall is an entangled, varied and contested relationship between religion and the State.

Constitution of the UK

The United Kingdom is made up of four distinct countries: England, Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland. However, “Great Britain” consists of England, Wales and Scotland only. The latter term was developed after an Act of Union united England and Scotland under the same monarch and Parliament in 1707. England and Wales had been united much earlier - in 1536 to be precise - when Wales was in effect incorporated into England. Another Act of Union followed in 1801, which merged Great Britain with Ireland to produce a new kingdom called the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland, or the UK for short. The Government of Ireland Act 1920 established Northern Ireland out of the six north-eastern counties in Ireland; the remaining 26 counties, initially “Southern Ireland” became the independent Irish Free State in 1922. Thus Northern Ireland has never been part of Great Britain.

Although the Church of England became the established church through an act of Parliament, it does not mean that it is identified with the State

There are several levels of government in Great Britain. The supreme legislative body is Parliament, which meets in Westminster (London). Headed by the Sovereign, it has two chambers: the upper chamber, or House of Lords, and the lower chamber, the House of Commons. Currently around 790 members are eligible to take part in debates in the House of Lords; the majority of these are life peers. Although there are over 800 hereditary peers, since 1999, only 92 have been eligible to sit in the House of Lords. No peers are currently directly elected, although House of Lords reform has been on the political agenda since the late 1990s. All 650 members of the House of Commons (which includes representatives from Northern Ireland) are directly elected.

While subject to the British Parliament, Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland also have their own separate parliaments or assemblies. The Scottish Parliament was restored in 1999 after an interval of nearly three centuries, while the National Assembly for Wales and the Northern Ireland Assembly were set up in 1998. All three bodies have elected members. The Scottish Parliament is responsible for “devolved matters”, including education and training, health and social services and local government; and the UK Parliament in Westminster holds responsibility for “reserved matters” such as defense, foreign policy and employment. There is a similar distinction in Wales between “devolved” and “reserved” powers, although more powers are reserved to Westminster in the National Assembly for Wales than in the Scottish Parliament. In September 2014, a referendum on whether Scotland should become an independent country was conducted; 45 per cent voted in favor and 55 per cent against, thus Scotland remains in the UK.

Northern Ireland is excluded from the remaining discussion, first because it is not part of Great Britain, but also because it has its own very complicated history, resulting in a particular political and legal situation. The role of religion is crucial in Northern Ireland, but is utterly different from that in Great Britain.1

There are other significant differences between England and Wales, on the one hand, and Scotland, on the other. Scotland has a separate system of education, and a distinctive legal system which is partly codified; England and Wales, in contrast, are subject to a common law system based on judicial precedents. Important differences also exist in terms of religious establishment as discussed below. To avoid confusion, the rest of this article focuses on the situation in England and Wales, unless otherwise stated.

Church and State

Prior to the Reformation of the 1530s, the Church in England was under the authority of Rome, with the Pope as head of the English Church. Under the Act of Supremacy 1534, King Henry VIII replaced the Pope as the “Supreme Head” of the church. In 1553, Rome’s jurisdiction was temporarily restored under Queen Mary I, but this was reversed after the accession of Queen Elizabeth I in 1558 who became “Supreme Governor” of the church in 1559. The first Elizabethan Archbishop of Canterbury was appointed in December 1559 and has remained the “Primate of all England” (i.e. the first bishop) ever since, except between 1646 and 1660 when episcopacy was abolished by Parliament before being restored by King Charles II. In addition to his primacy in England, the Archbishop of Canterbury is also recognized as the head of the wider Anglican Communion, which includes all churches throughout the world in communion with the Church of England, although he does not exercise direct authority over them.

Although the Church of England became the established church through an act of Parliament, it does not mean that it is identified with the State or that it is a department of State operating under a Ministry for Religious Affairs.2

On the contrary, several different government departments have responsibilities for religious issues. These include the Department for Communities and Local Government (DCLG), established in 2006, which has a Minister for Faith and a Faith Engagement Team as the main point of contact with the government for faith-based organizations.3 The nature of establishment as such has evolved and weakened over time, but some key features remain. The Sovereign is still the Supreme Governor of the Church of England and must be a member of it. The Sovereign formally appoints all bishops, but in practice the appointments are made by the Crown Nominations Commission and approved by the Prime Minister. Since 2007, the convention has been that the Prime Minister will accept the Commission’s recommendation.

In the intervening 150 years religious diversity had increased significantly, particularly following post-World War II labor migration from colonies and former colonies

Before 1919, unlike all other religious denominations, the Church of England was not free to govern itself. All changes had to be introduced into and approved by Parliament as public statutes. This changed in 1919, when a Church Assembly (known as the General Synod since 1969) was established to recommend changes –called ‘Measures’– which, if approved, have the force of statutes. The Synod has three sections, called houses, one for bishops, one for clergy and one for laity. Major changes recommended by the General Synod still have to be approved by Parliament; for example, Church of England ministers are not permitted to carry out marriages of same-sex couples under legislation enacted in 2014 and for this to change, the Measure would have to be passed first by the General Synod and then by Parliament.4 Equally, however, the General Synod can block changes favored by the Government and a majority of the Members of Parliament. It did so notably in November 2012 when a Measure to allow the appointment of women bishops failed to achieve the required two-thirds majority in each house. It was finally passed in July 2014.5

The most senior 26 Anglican bishops serve in the House of Lords as Lords Spiritual until they retire; they attend on a rota basis. Other religious leaders have also become members of the House of Lords, but on the basis of their personal and professional roles rather than the offices they hold.6 While bishops and archbishops have made repeated, valuable and generally well-received interventions in debates in the House of Lords in recent decades,7 they tend to vote less than other members of the House and their numbers rarely affect the overall outcome.8 One partial exception occurred in June 2013, when an unusually high number of bishops (14) attended the key debate on the Marriage (Same Sex Couples) Bill. They did not vote as a bloc, however, with nine voting for an amendment to deny the Bill a second reading and five abstaining.9

Welsby10 emphasizes that the supposition that the Church of England receives large sums of money from the State is incorrect. The only money received from the State is, firstly, money paid, as salaries, to chaplains in the armed forces, prisons and National Health Service (see more on this below) and, secondly, government grants for the care of listed buildings. The Church of England has an annual budget of around £1,000 million; around three-quarters of this is raised by worshippers in parishes, with the remainder primarily coming from money raised from investments and other assets and from reserves. A significant amount (around £80 million annually) is recovered in tax from Her Majesty’s Revenue and Customs, but there are no special taxes to pay for church expenditure unlike those, for example, that help fund the Catholic Church and major Protestant Churches in Germany.11 The point is reinforced by Cranmer et al, who state: ‘Not since the first half of the nineteenth century has it (the Church of England) received any state subvention not equally available to other denominations’.12

The Church of Scotland and the Church in Wales

Sandberg13 argues that the Church of Scotland has a “milder form of establishment” than the Church of England. The Sovereign swears an Oath on Accession to protect the Church of Scotland and its Presbyterian form of Government, but is not its Supreme Governor. The Church of Scotland Act of 1921 also asserted the Church’s right to legislate and adjudicate in all its matters of doctrine, worship, government, and discipline, although this right was tested by the outcome of a legal case in 2005 (Percy v Church of Scotland Board of National Mission). There are also differences in respect of marriage between the Church of England and the Church of Scotland.14

The position of the Church in Wales is different again. In 1920 the Church of England in Wales (now known as the Church in Wales) was formally disestablished following a sustained campaign originating in the nineteenth century, which culminated in the Welsh Church Act 1914; this was implemented following World War I.15 The Act re-established the Church in Wales as a voluntary society under the ecclesiastical authority of the Church of England; this meant, among other things, that the Crown lost all powers of appointment and no bishops of the Church in Wales were to sit in the House of Lords.16

The Contemporary Religious Landscape

For the first time since 1851, the 2001 decennial national Census included questions on religion. In the intervening 150 years religious diversity had increased significantly, particularly following post-World War II labor migration from colonies and former colonies. Prior to 2001, a number of faith-based organizations including the Muslim Council of Britain, the Board of Deputies of British Jews and some Christian groups had joined forces to press for such a question to be included. They were joined by a number of academics and Government representatives.17 The Government and the Office for National Statistics (which implements the Census) were persuaded by their arguments. The Office for National Statistics (ONS) concluded: ‘The main need for the religion question is to provide a finer description of ethnic minorities in order to target services more effectively’.18 A religious question was also included in the 2011 census. The questions in England and Wales and in Scotland differed in both 2001 and 2011. In England and Wales, there was one question, ‘What is your religion?’ in both 2001 and 2011. In Scotland, there were two questions: ‘What religion, religious denomination or body do you belong to?’ and ‘What religion, religious denomination or body were you brought up in?’ in 2001, but only the (same) first question was asked in 2011. The response categories also differed. The question was voluntary (all other questions were compulsory) and enjoyed a relatively high proportion of respondents. A mere 7.7 per cent chose not to answer it, although as noted by Weller et al,19 some compulsory questions have had lower completion rates.

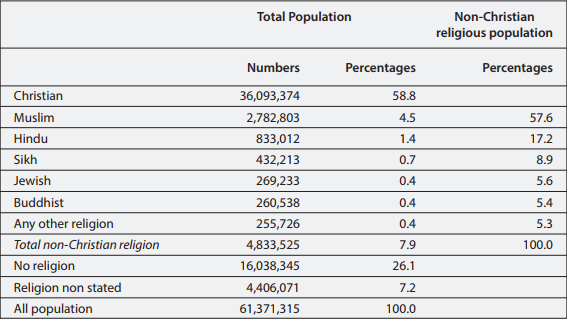

Both, the form of the questions and the results, have been criticized. Many expressed surprise that the figure for Christians in Britain in 2001 (71.9%) was as high as it was, which sparked a debate over the extent to which this figure measured identity or affiliation, rather than membership or practice. Prior to the 2011 Census, secular groups embarked on a major campaign to persuade those who had selected “Christian” in 2001 for reasons of identity to select the “no religion” category in 2011, and certainly there was a marked shift in the pattern of responses. The number of self-identifying Christians in Britain fell to 59 per cent in 2011, while the no religion figure rose from 15 to 26 per cent. The no religion figure in Scotland (36.7%) and Wales (32.1%) was higher than in England (24.7%); there were also marked differences in responses within England.20 For all the criticism of the Census question, it remains the best available resource for assessing the religious population of Britain. The overall results for 2011, aggregated from the responses in England and Wales to the single question on religion and in Scotland to the question on religious belonging, were as follows:21

Census data indicate that there is a strong degree of overlap between some religious and ethnic minority groups in Great Britain, but less so between others

The composition of the non-Christian population also changed markedly between 2001 and 2011; the Muslim share increased from 51.9 to 57.6% of the non-Christian religious population. There were also slight increases in the relative size of the Buddhist and no religion groups and a decline in the Hindu, Sikh and Jewish shares.

The Census in England and Wales (unlike in Scotland) does not break down the Christian category by denomination and does not provide estimates of membership. However, another important source, UK Church Statistics, does precisely that.22 The data are compiled in a very different way from the Census, being based on a voluntary survey of Christian denominations; the latest figures are for 2013. On the basis of these data, Brierley calculates that in 2013, there were 1.22 million Anglicans and 1.01 million Catholics in Great Britain; these formed easily the two largest denominations. The third largest group consists of Orthodox Christians (456,000), followed by Presbyterians (primarily members of the Church of Scotland) (444,000), members of Independent Churches (226,000), Methodists (219,000) and members of the so-called New Churches (210,000).23 Brierley also stated that in 2013 there were 36,099 Christian ministers and 48,371 Christian churches.24

Population of Great Britain: by religion, April 2011

Minority Religious Groups

Census data indicate that there is a strong degree of overlap between some religious and ethnic minority groups in Great Britain, but less so between others. Brierley25 shows that in 2011, 96 per cent of Hindus were Asian, 93 per cent of Christians were White, as were 92 per cent of Jewish people, while 87 per cent of Sikhs were Asian. However, only 68 per cent of Muslims and 60 per cent of Buddhists were Asian; 10 per cent of Muslims were Black and 8 per cent were White, while 33 per cent of Buddhists were White. The “no religion” population was also overwhelmingly White (93%). In addition, the proportion of Whites who were Christians fell between 2001 and 2011 from 76 per cent to 65 per cent, with parallel falls for most ethnic groups except for Asians.

As noted above, the largest and fastest-growing religious minority group is that of the Muslims and it is this group which also been subject to the most political attention in the past decade. British Muslims originate from a variety of countries, but the largest section of the community comes from the Asian subcontinent, particularly Pakistan and Bangladesh. It should be noted, however, that around half of the current Muslim population was born in Britain.26 Umbrella organizations have been criticized for their inability to represent all Muslims, although the Muslim Council of Britain has, at times, come closest to fulfilling this representative role.27

Since the early 2000s, Government initiatives on religion have often emphasized social cohesion and the mitigation of extremism, largely in response to the attacks in the US in September 2011 (known as 9/11) and the bombings in London in July 2005 (known as 7/7). For example, the top 19 UK areas in receipt of community cohesion funding from 2008 to 2011 were the 19 areas that had the largest Muslim populations.28 Anti-terrorism legislation disproportionately affected Muslims, while Imams and other Muslims were also actively recruited to help implement the controversial counter-terrorism “Prevent” strategy introduced by the Labor Government in response to 7/7; the Conservative-Liberal Democrat Coalition also adopted a modified form of that strategy.29 “Prevent,” with its focus on Muslims and mixing of security and cohesion concerns, continues to garner criticism. O’Toole et al.30 conclude that this strategy is highly problematic for state-Muslim engagement. Francis and van Eck note, however, that although “much of the focus of counter-terrorism efforts continue to be targeted at Muslim groups, the religious roots of violent action have been downplayed” more recently.31 That said, despite a tradition of relative accommodation compared to other Western European countries,32 Muslims have been experiencing increasing discrimination and prejudice in Britain.33 Such discrimination has often been termed Islamophobia, a term brought to public attention by the Runnymede Trust in 1997.34

Religion and the Law

Sandberg35 distinguishes between “religion law” and “religious law,” the former being the “external” temporal laws made by the State and other bodies affecting religious individuals and groups, the latter the “internal” laws of religious groups. Three key aspects of religion law concern registration and charity law, human rights law and discrimination law. In the UK, in contrast to many other European countries, religious organizations are not required to register as a religion, but they can register as a charity. For religious bodies other than the Church of England and the Church of Scotland, the applicable legal principles are those of the general law of charities and especially of charitable trusts. The non-established churches are essentially organized as voluntary associations, and their property is held by trustees (which may be registered companies) under the ordinary secular law. They have no special status.

Not all religious claims are recognized by the Charity Commission, the body responsible for overseeing charity law; for example, it rejected the application of the Church of Scientology in 1999 and the Gnostic Centre in 2003. However, the Druid Network was registered in 2010, a decision that provoked controversy.36 The Charity Commissioners refused various calls for the charitable status of the Unification Church to be removed in the 1970s despite Government pressure.37 They also opposed an attempt by a Roman Catholic adoption agency, Catholic Care, to amend its charitable objects to enable it to restrict its services to opposite sex couples after the passing of the Civil Partnership Act 2004 enabling same sex couples to enter into a legally recognized union.38The case was eventually resolved in favor of the Charity Commission’s position in 2012.

Since the UK joined the European Union (EU) in 1973, EU Law has had a direct effect on its law, and UK courts are bound by the decisions of the European Court of Justice. They must also “take into account” decisions of the European Court of Human Rights (ECtHR).39 As a member of the Council of Europe, the European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR) has had a considerable impact on the relationship between religion and the State in Britain. For example, the Human Rights Act 1998 (HRA), which enshrined the ECHR into domestic law beginning in 2000, made it unlawful for a public authority, excluding Parliament, to act in a way which was incompatible with a Convention right. However, the HRA does not make the ECHR specifically applicable between private parties, and the courts must ultimately follow the terms of the HRA rather than the ECHR. Article 9 of the ECHR is the most important article in this context. Article 9 (1) provides an absolute right to freedom of thought, conscience and religion (including to change religion). However, the freedom to manifest a religion or belief is qualified by “necessary” limitations, with these being set out in Article 9 (2).40 Prior to the passage of the HRA, the only religious groups that received explicit protection (under the Race Relations Act) were Jews and Sikhs, who were classified as races; now all religions are protected and Article 9 cases can be heard before UK judges.41

The Employment Equality (Religion or Belief) Regulations 2003 for the first time prohibited discrimination in employment and vocational training on grounds of religion or belief. The Equality Act 2006 extended this to cover the provision of goods and services, while the Equality Act 2010, as well as consolidating existing legislation, established the Public Sector Equality Act (PSED). The PSED (which came into force in 2011) requires public authorities to pay due regard to the need to eliminate discrimination, advance equality of opportunity and foster good relations; whereas previous equality duties had applied only to sex, race and disability, this duty now applies to all protected characteristics, including religion or belief.42 Religion or belief is defined very broadly in the Equality Act 2010 to include any religion, and any religious or philosophical belief, including a lack of religion and a lack of belief. What qualifies as a belief has in effect been decided by the courts in a series of judgments, the key elements being that a belief must be genuinely held; must be a belief and not an opinion based on the present state of information available; must be related to a weighty and substantial aspect of human life and behavior; must attain a certain level of cogency, seriousness, cohesion and importance; must be worthy of respect in a democratic society; must not be incompatible with human dignity; and must not conflict with the fundamental rights of others.43 Sandberg44 has argued that Employment Tribunals have used these five requirements of a definition of belief “in inconsistent ways to often reach arbitrary decisions.”

The 1998 School Standards and Framework Act (SSFA) introduced the concept of schools of “a religious character” in England

The number of legal cases brought to Employment Tribunals on grounds of religion or belief remains relatively low. In 2013-14, 584 claims were accepted by Tribunals, compared with 13,722 claims for sex discrimination, and very few claims are successful.45Nevertheless, there have been a small number of significant cases, which have attracted considerable media attention, not least because of their long-running nature.46 These have resulted in a gradual development of case law in this area; a particularly important decision was in Eweida v British Airways, involving Nadia Eweida, a member of the check-in staff at British Airways who wished to wear a cross at work in contravention to a uniform policy. This case was finally decided at the ECtHR in January 2013. One outcome has been that it is now much more difficult for private sector (as well as public sector) organizations to ignore a request from an individual to manifest their religion or belief and offer them instead the option of resigning; such requests also need to be taken seriously when made by only one individual. The fact that many of the high profile cases have been taken by Christians – who have generally lost, although Eweida, who was Coptic Christian, won her case – has fuelled the impression in some quarters that Christians, far from being a privileged group as others maintain, have in fact become marginalized in British society.47

Education

Ownership and Management of Schools

The education system in England and Wales is extremely complex; it is moreover an area of intricate interaction between the State and religion (the Church of England and the Roman Catholic Church in particular). Overseen by a government department, currently the Department for Education, schools in England and Wales are divided between those funded by the State (maintained schools) and those funded independently (independent schools). There are now eight types of State-maintained schools: community schools, foundation schools, voluntary aided (VA) schools, voluntary controlled (VC) schools, academies, free schools, community special schools, and foundation special schools. All these types of schools, except community schools and community special schools, can be designated as schools with a religious character (discussed below) or as they are popularly, but loosely, termed “faith schools.” Most VA and VC schools were originally Church schools prior to being brought within the remit of the State system under the 1944 Education Act.48 They differ, however, in respect of how they are governed and funded.49

The 1998 School Standards and Framework Act (SSFA) introduced the concept of schools of “a religious character” in England. Under the SSFA, the Secretary of State can designate any foundation or voluntary school as having a religious character.50 Under the Equality Act 2010, these types of schools are permitted to discriminate on grounds of religion or belief in terms of the employment of staff, the admission of pupils, the content of the curriculum, and religious education. However, there are significant differences between schools of a religious character in terms of what they are permitted to do. The general rule is that VA schools have greater flexibility than VC and foundation schools with a religious character in terms of appointing staff, selecting pupils and choosing which subjects to teach, while academies and free schools with a religious character have the most flexibility.51

In January 2014, 37 per cent of all State-funded primary schools (for ages 4-11) in England were designated as having a religious character. This included virtually all VA and VC schools. However, only 19 per cent of all secondary schools (for ages 11-18) were so designated. While 95 per cent of VA schools were of a religious character, only 54 per cent of VC schools were. Twenty-six per cent of primary academies were of a religious character, compared to only 15 per cent of their secondary equivalents. Most primary schools of a religious character (71 per cent) were Church of England schools, but the majority of secondary schools of a religious character (51 per cent) were Roman Catholic schools. While Church of England and Methodist schools can either be VC or VA schools, all Catholic primary and secondary schools are VA schools.52 Almost all schools with a religious character are Christian. There are, however, exceptions: in January 2014, there were 36 primary and 13 secondary schools that were Jewish, Muslim, Sikh or “Other”.

Pupils at maintained schools which are not of a religious character are required to participate in a daily act of collective worship of a mainly Christian character, though worship from other faiths can be incorporated

The key issue of dispute with regard to education is whether or not there should be any place in the State system for schools of a religious character. A major opponent of such schools is the Accord Coalition which brings together a range of religious, Humanist and secular organizations. There are a number of key points of contention. These include whether or not schools of a religious character are elitist, whether they encourage cohesion or division, and whether or not they provide a higher quality of education than other schools. Different views are also held about whether or not they should be funded by the State at all.53

Religious Education in England and Wales

Since 1870 England has required non-denominational religious education (RE) in its maintained schools. The 1944 Education Act introduced the Agreed Syllabus for Religious Instruction (RI), a non-denominational form of teaching; each Local Education Authority (LEA) in England had to convene an Agreed Syllabus Conference (ASC) consisting of four committees to agree upon its RI syllabus;54 RI later evolved into the current system of Religious Education (RE). The 1988 Education Reform Act laid down that RE would not form part of the National Curriculum because of the existence of the ASCs, although it would be a compulsory subject. Local ASCs continue to draw up RE syllabi in community schools. These are overseen by local regulatory bodies called Standing Advisory Councils of Religious Education (SACREs), which advise local authorities on matters of RE and collective worship (see below). The syllabi are set every five years and must be non-confessional. As discussed by Donald with Bennett and Leach,55 RE in community schools and other schools without a religious character must be “in the main Christian, whilst taking account of the teaching and practices of the other principal religions represented in Great Britain.” RE provision in community schools is inspected by the Office for Standards in Education, Children’s Services and Skills (Ofsted), which carries out up to 60 RE subject survey inspections in primary and secondary schools per year.

In VC and foundation schools with a religious character, RE syllabi are set by the ASCs and are non-confessional unless parents request that RE be taught in accordance with the trust deeds and faith of the school. Provision is inspected, but by people chosen by the governing body, not by Ofsted, and inspectors are normally, but not always, drawn from the relevant faith group’s inspection service. In VA schools with a religious character, the RE syllabus is set by the governors in accordance with the tenets of the faith of the school unless parents request non-confessional RE as set by the local ASC. As in the case of VC and foundation schools, RE is inspected by people chosen by the governing body. In academies and free schools with a religious character, RE must be “in accordance with the tenets and practices of the religion or religious denomination.” Academies and free schools with a religious character are required by their funding constraints to arrange for the inspection of any denominational RE. When choosing an inspector, they must consult the relevant religious body. Academies and free schools without a religious character follow the same inspection provision as community schools.

Teachers cannot be required to teach RE except where the law provides otherwise. This would normally be the case in a school with a religious designation. Parents are also permitted to request that their children opt out of receiving RE, although the pupils themselves cannot directly request to do so.

Worship

According to the Education Reform Act 1988, pupils at maintained schools which are not of a religious character are required to participate in a daily act of collective worship of a mainly Christian character, though worship from other faiths can be incorporated.56In foundation and voluntary schools of a religious character the worship can be in the character of the religious group. Parents have the right to withdraw children from collective worship, and pupils 16-18 can also opt out of religious worship. Also, even if the school does not have a religious character, if the majority of pupils are from a faith other than Christianity, the school can apply to lead worship mainly in the character of that faith.

Chaplaincies

As noted above, the State funds religious personnel to provide religious activities and services such as prayer and counseling in the armed forces, the prison service and the National Health Service (NHS). Chaplains also work in higher education institutions, in schools and, as a more recent development, in airports, shopping centers, emergency services and in sport. Many salaried chaplains are funded by the Church of England, or by another religious group or denomination, either jointly with the organization in which they are employed or solely by it.57 There are no figures for the total number of full-time and part-time, paid and unpaid, chaplains in all these settings combined; however, in 2012, there were just over one thousand Church of England chaplains in the armed forces, prisons, hospitals, schools, higher and further education and other areas.58 It is also estimated that there are around 450 Muslim chaplains in Britain, including part-time chaplains and volunteers,59 but there are still very few chaplains representing other religions or non-faith perspectives, such as Humanism.

A key issue of controversy is that of funding, as noted by Davie:60 “who should pay for the chaplain and how far should his or her ministry extend?” Another area of dispute in some secular contexts, e.g. hospitals, is whether chaplains alone should be responsible for providing spiritual services, or whether it is permissible for other non-specialist staff, such as nurses and doctors, to do this. There have been important legal cases involving medical staff wishing to pray for their patients.

Conclusions and Areas of Controversy

This article has explored some of the key issues affecting religion or belief in Great Britain in the twentieth-first century. Religion is now at the centre of sociological debate in a way that it was not in the 1970s or 1980s; this has helped to reshape old controversies and to introduce new ones. Amongst the longstanding controversies are those that relate to an established Church of any kind, bearing in mind that the nature of the debate has changed. As Ganiel and Jones61 point out, calls for disestablishment are less frequent now than in the nineteenth century and those who continue to call for it are no longer Protestant Dissenters (as in the past), but rather those who adopt a secularist agenda. Instead, the debate focuses on particular aspects of establishment, notably the continued existence and legal privileges of schools of a religious character, i.e. “faith schools.”

There is also continued debate, based largely on the interpretation of data from the Census and other statistical sources, about whether Great Britain is still a Christian country, as historically it clearly was, or whether it is now an essentially secular State. The reality is in fact much more nuanced than this, an ambiguity captured in Weller’s much cited phrase: Britain is simultaneously “Christian, secular and religiously plural.”62 Furthermore, Weller et al63 suggest that during the first decade of the current century, Britain became “more secular, less Christian and more religiously plural.”

Despite everything, however, the historic connection between the Church of England and the State endures

The position of minority religious groups in British society is also keenly debated, although as Nye and Weller64 point out, this is nothing new. But once again the nature of the debate alters. For several centuries after the Reformation, Roman Catholics were seen as the dangerous “other”; in the 1960s and 1970s this place was taken by so-called New Religious Movements; currently the role is filled by Muslims.

Newer controversies are beginning to emerge, which may or may not turn out to be as significant as earlier ones. One such controversy is the argument put forward in some quarters as a result of recent legal judgments: namely that Christians are increasingly marginalized in British society. Another concerns a so-called hierarchy of equality rights, with sexual orientation usually considered to be at the top of the hierarchy and religion or belief at the bottom – a view held by Trigg,65 for example, although Johnson and Vanderbeck66 argue the opposite.

All of these debates demonstrate that the relationship between State and religion continues to change as the religious composition of the country alters. Despite everything, however, the historic connection between the Church of England and the State endures. In her reflections on religion in Great Britain since World War II, Woodhead67 argues succinctly that “Religion in Britain is not what it used to be.” There is every likelihood that over the next fifty years or so, the relationship between State and religion will evolve in different ways, with new controversies emerging and others moving in different directions reflecting the essentially pragmatic, piecemeal and composite nature of religion-State relations in this country.

Endnotes

- Claire Mitchell, Religion, Identity and Politics in Northern Ireland (London: Ashgate, 2006).

- Paul A. Welsby, How the Church of England Works (London: CIO Publishing, 1985), p. 45.

- Warwick Hawkins, “Faith in Government: The Work of the Faith Engagement Team”, Public Spirit, (October 7, 2013), accessed April 19, 2015 from http://www.publicspirit.org.

uk/faith-in-government/. - Equality and Human Rights Commission, “The Marriage (Same Sex Couples) Act 2013: The Equality

and Human Rights Implications for Marriage and the Law in England and Wales”, (2014), accessed

April 19, 2015 from http://www.equalityhumanrights.com/ publication/marriage-same-sex- couples-act-

2013-marriage-and-law. - Grace Davie, Religion in Britain: A Persistent Paradox (Oxford: Wiley Blackwell, 2015), p. 127.

- Paul Weller, Kingsley Purdam, Nazila Ghanea and Sariya Cheruvallil-Contractor, Religion or Belief, Discrimination and Equality (London: Bloomsbury, 2013), p. 32.

- Davie, Religion in Britain: A Persistent Paradox, p. 96.

- Andrew Partington and Paul Bickley, Coming Off the Bench: The Past, Present and Future of Religious Representation in the House of Lords (London: Theos, 2007).

- Davie, Religion in Britain: A Persistent Paradox, p. 96; 109 note 9.

- Welsby, How the Church of England Works, p. 63.

- Weller et al, Religion or Belief, Discrimination and Equality, p. 32. For a summary of the funding of the Church of England, see https://www.churchofengland.

org/about-us/funding.aspx. - Frank Cranmer, John Lucas and Bob Morris, Church and State: A Mapping Exercise (London: University College London Constitution Unit, 2006), p. 6.

- Russell Sandberg, Law and Religion (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2011), pp. 70-72.

- Sandberg, Law and Religion, pp. 71-72.

- Kenneth O. Morgan, Rebirth of Nation: Wales 1880-1980 (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1990).

- Sandberg, Law and Religion, pp. 78-80.

- Weller et al, Religion or Belief, Discrimination and Equality, p. 35.

- Joanna R. Southworth, “‘Religion’ in the 2001 Census for England and Wales”, Population, Space and Place, 11, 2, (March, 2005), pp. 75-88, p. 83.

- Weller et al, Religion or Belief, Discrimination and Equality, pp. 35-37.

- Davie, Religion in Britain: A Persistent Paradox, pp. 42-46; Weller et al, Religion or Belief, Discrimination and Equality, pp. 34-38; Peter Brierley, UK Church Statistics 2: 2010-2020 (Tonbridge: ADBC, 2014), p. S14.

- Source: National Statistics website: www.statistics.gov.uk Crown copyright material is reproduced with the permission of the Controller of HMSO.

- Brierley, UK Church Statistics 2: 2010-2020.

- Brierley, UK Church Statistics 2: 2010-2020, Table 1.2.

- Brierley, UK Church Statistics 2: 2010-2020, Table 1.1.1.

- Brierley, UK Church Statistics 2: 2010-2020, p. S14.3.

- Davie, Religion in Britain: A Persistent Paradox, p. 61.

- Therese O’Toole, Daniel Nilsson DeHanas, Tariq Modood, Nasar Meer and Stephen Jones, Taking Part: Muslim Participation in Contemporary Governance (Bristol: Centre for the Study of Ethnicity and Citizenship, University of Bristol, 2013), accessed April 19, 2015 from http://www.bristol.ac.uk/

ethnicity/projects/ muslimparticipation/. - Matthew Francis and Amanda van Eck Duymaer van Twist, “Religious Literacy, Radicalization and Extremism”, Adam Dinham and Matthew Francis (eds.), Religious Literacy in Policy and Practice (Bristol: Policy Press, 2015), pp. 113-134, p. 128.

- Francis and van Eck Duymaer van Twist, “Religious Literacy, Radicalization and Extremism”, pp. 115-117.

- Therese O’Toole, Nasar Meer, Daniel Nilsson DeHanas, Stephen Jones and Tariq Modood, “Governing through Prevent? Regulation and Contested Practice in State–Muslim Engagement”, Sociology, accessed February 20, 2015 from http://soc.sagepub.com/

content/early/2015/02/19/ 0038038514564437.full.pdf+html - Francis and van Eck Duymaer van Twist, “Religious Literacy, Radicalization and Extremism”, pp. 128-129.

- Joel S. Fetzer and J. Christopher Soper, Muslims and the State in Britain, France, and Germany (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2005).

- Clive Field, “Revisiting Islamophobia in Contemporary Britain, 2007-10”, Marc Helbling (ed.), Islamophobia in the West: Measuring and Explaining Individual Attitudes (London; New York: Routledge, 2012), pp. 147-161.

- Chris Allen, Islamophobia (Farnham: Ashgate, 2010).

- Sandberg, Law and Religion, pp. 10-14.

- Sandberg, Law and Religion, p. 45; Weller et al, Religion or Belief, Discrimination and Equality, pp. 58-59.

- Eileen Barker, “Tolerant Discrimination: Church, State and the New Religions”, Paul Badham (ed.), Religion, State, and Society in Modern Britain (Lampeter: The Edwin Mellen Press, 1989), pp. 185-208, p. 196.

- The Marriage (Same Sex Couples) Act was subsequently enacted in 2014 enabling same sex couples to marry in civil ceremonies but at the same time protecting religious organizations and representatives from legal challenge if they do not wish to marry same sex couples.

- Whether UK courts are bound by ECtHR decisions is disputed. See Roger Masterman, “Are UK Courts Bound by the European Court of Human Rights?” Durham Law School Briefing (2014), accessed May 5, 2015 from https://www.dur.ac.uk/law/

research/briefings/ - Sandberg, Law and Religion, pp. 82-87.

- Sandberg, Law and Religion, p. 32; Weller et al, Religion or Belief, Discrimination and Equality, pp. 42-43.

- Weller et al, Religion or Belief, Discrimination and Equality, pp. 43-56; Lucy Vickers, “Promoting Equality or Fostering Resentment? The Public Sector Equality Duty and Religion or Belief,” Legal Studies, 31, 1, (January, 2011), pp. 135-158.

- Russell Sandberg, Religion, Law and Society (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2014), pp. 39-48.

- Sandberg, Religion, Law and Society, p. 42.

- Rebecca Catto and David Perfect, “Religious Literacy, Equalities and Human Rights”, Adam Dinham and Matthew Francis (eds.), Religious Literacy in Policy and Practice (Bristol: Policy Press, 2015), pp. 135-163, p. 137.

- Six such cases are discussed in Catto and Perfect, “Religious Literacy, Equalities and Human Rights.”

- Christians in Parliament, Clearing the Ground Inquiry: Preliminary Report into the Freedom of Christians in the UK (London: Christians in Parliament, 2012), accessed April 19, 2015, http://www.eauk.org/current-

affairs/publications/clearing- the-ground.cfm. - Lucy Vickers, “Religious Discrimination and Schools: The Employment of Teachers and the Public Sector Equality Duty”, Myriam Hunter-Henin (ed.), Law, Religious Freedoms and Education in Europe (Farnham: Ashgate, 2012), pp. 87-104, pp. 87-88.

- Sandberg, Law and Religion, p. 152.

- Sandberg, Law and Religion, p. 161.

- Elizabeth Oldfield, Liane Hartnett and Emma Bailey, More Than an Educated Guess: Assessing the Evidence on Faith Schools (London: Theos, 2013), accessed April 19, 2015 from http://www.theosthinktank.co.

uk/files/files/More%20than% 20an%20educated%20guess.pdf, pp. 18-20; Sandberg, Law and Religion, pp. 160-167. - Department for Education, “Schools, Pupils and Their Characteristics: January 2014”, (2014),

accessed April 19, 2015 from https://www.gov.uk/government/statistics/schools-pupils-and- their-

characteristics-january-2014. - Oldfield et al, More Than an Educated Guess: Assessing the Evidence on Faith Schools; Accord Coalition “Databank of Independent Evidence on Faith Schools”, (December 2014), accessed April 19, 2015, http://accordcoalition.org.uk/

wp-content/uploads/2013/12/ Databank-of-Independent- Evidence-on-Faith-Schools- April-2014.pdf. - Adam Dinham and Robert Jackson, “Religion, Welfare and Education”, Linda Woodhead and Rebecca Catto (eds.), Religion and Change in Modern Britain (London: Routledge, 2012), pp. 272-294, pp. 280-281.

- Alice Donald, Karen Bennett and Philip Leach, Religion or Belief, Equality and Human Rights in

England and Wales. Equality and Human Rights Commission Research Report no. 84 (Manchester:

Equality and Human Rights Commission, 2012), accessed April 19, 2015, http://www.equalityhumanrights.com/ publication/research-report- 84-religion-or-belief- equality-and-human-rights- england-and-wales, p. 169. - David McClean, “State and Church in the United Kingdom”, Gerhard Robbers (ed.), State and Church in the European Union (Baden-Baden: Nomos Verlagsgesellschaft, 1996), pp. 307-322, p. 316.

- Jeremy Clines with Sophie Gilliat-Ray 2015 “Religious Literacy and Chaplaincy”, Adam Dinham and Matthew Francis (eds.), Religious Literacy in Policy and Practice (Bristol: Policy Press, 2015), pp. 237-256, pp. 238-239.

- Brierley, UK Church Statistics 2: 2010-2020, p. S2.4.

- Clines with Gilliat-Ray, “Religious Literacy and Chaplaincy”, p. 243.

- Davie, Religion in Britain: A Persistent Paradox, p. 114.

- Gladys Ganiel and Peter Jones, “Religion, Politics and Law”, Linda Woodhead and Rebecca Catto (eds.), Religion and Change in Modern Britain (London: Routledge, 2012), pp. 299-321, pp. 300-301.

- Paul Weller, Time for a Change: Reconfiguring Religion, State and Society (London: T&T Clark, 2005), p. 73.

- Weller et al, Religion or Belief, Discrimination and Equality, p. 38.

- Malory Nye and Paul Weller, “Controversies as a Lens on Change”, Linda Woodhead and Rebecca Catto (eds.), Religion and Change in Modern Britain (London: Routledge, 2012), pp. 34-54.

- Roger Trigg, Equality, Freedom and Religion (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2012).

- Paul Johnson and Robert M. Vanderbeck, Law, Religion and Homosexuality (Abingdon: Routledge, 2014).

- Linda Woodhead, “Introduction”, Linda Woodhead and Rebecca Catto (eds.), Religion and Change in Modern Britain (London: Routledge, 2012), p. 1.