Introduction

After the announcement of the restoration of its independence, Azerbaijan immediately faced many challenges inherited from the Soviet Union. First and foremost was the unstable political situation in the country, problematized by economic collapse and war with Armenia. In order to solve its economic problems, Azerbaijan had only one advantage: energy resources. Once known worldwide as one of the preeminent places for the production of oil, Azerbaijan needed to restore its reputation. However, it was necessary to start the development of new fields and bring these resources to the world markets. Independently, Azerbaijan couldn’t do it. It lacked the necessary financial sources and technologies. To acquire them, it was necessary to attract Western companies.

Turkey played an important role in Azerbaijan’s energy production and transport. It is worth noting that the restoration of Azerbaijan’s independence was also a landmark event for Turkey; less than a month after Azerbaijan declared its independence, on November 9, 1991, Turkey became the first country to recognize it.1 Both states have a common culture, ethnic and religious roots. That’s why relations between Turkey and Azerbaijan have always been closer than what is typical between two nation states, and may be better described by what is now a well established expression, “one nation, two states,” a term coined by President Heydar Aliyev during his official visit in Turkey in February 1994. The close relations between the two countries formed the basis for the development of economic ties.

With the collapse of the Soviet Union, new Turkic states which are rich in natural resources have appeared

Immediately after achieving its independence, Azerbaijan tried to restore its reputation as an oil country and initiate the large-scale production of its energy resources. An important component in this operation was the exploitation of Azerbaijan’s large, offshore fields. These offshore energy fields had been explored while Azerbaijan was still a part of the Soviet Union. However, at that time, the Soviet Union lacked both the capital and the necessary technology for extracting oil from these deep and complex structures. Given the USSR’s huge oil reserves in Siberia, which were more attractive for exploitation, the Azerbaijani fields remained undeveloped.

Despite the many difficulties, however, Azerbaijan managed to sign an agreement with Western companies which became known as the “Contract of the Century” forming a consortium which aimed at developing the offshore Azeri, Chirag and Deep Water Guneshli oil fields. The beginning of work on this project gave rise to a sustainable and productive cooperation between Azerbaijan and Turkey.

TPAO’s Role in Turkish-Azerbaijan Energy Relations

Along with eleven companies from eight countries, the Turkish state energy company TPAO (Türkiye Petrolleri Anonim Ortaklığı) became a member of the consortium. Turkey understood the opportunities that had opened up after the change in the geopolitical situation in Eurasia. With the collapse of the Soviet Union, new Turkic states which are rich in natural resources have appeared. The first such state among them with which Turkey was to develop economic relations was Azerbaijan. This cooperation was aided by the geographical proximity of the two countries, as well as Azerbaijan’s wish to balance the presence of Russia in the South Caucasus region. In turn, Turkey sought ways to ensure supply for its own domestic energy demand from alternative sources. TPAO was elected as the main tool for the implementation of these purposes.

TPAO submitted a report to the former Turkish president, Turgut Özal, stating its willingness to operate hydrocarbon exploration and production activities in Azerbaijan. Following negotiations between the political authorities in 1992, two national oil companies TPAO and SOCAR (State Oil Company of Azerbaijan Republic), signed a protocol to boost exploration and production activities by developing a direct cooperation in offshore and onshore fields, or by getting into a partnership(s) with foreign corporations which met with the Azerbaijani government’s approval.2 In the initial stage, TPAO’s share in the Azeri Chirag and Deep Water Guneshli oil fields was small, consisting of only 1.75 percent. However, the significance of Turkey’s participation in this project was that TPAO, for the first time in its history, participated in the development of a field outside of Turkey.

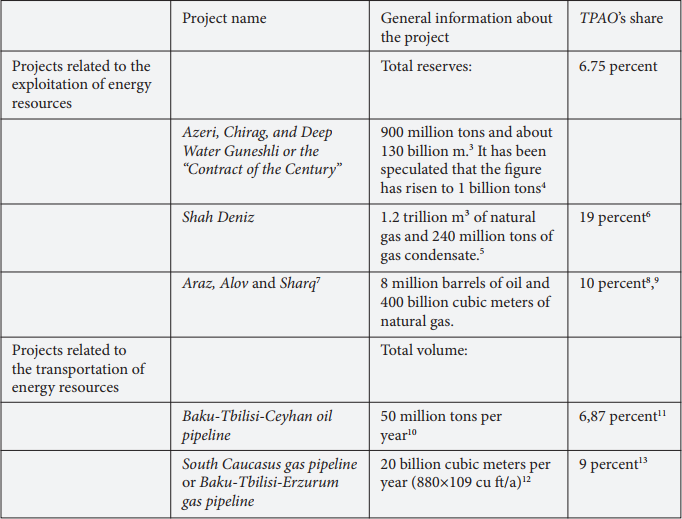

Subsequently, TPAO’s share in the project has increased, as SOCAR delivered percent of its share to TPAO. President Heydar Aliyev and Turkish Prime Minister Tansu Çiller signed an agreement on transferring the 5 percent of shares to TPAO in Baku on April 12, 1995.3 This project was not the only one in which TPAO participated. The table below describes the Azerbaijani projects in which TPAO is involved.

Table 1: TPAO’s Project Investment in Azerbaijan

It is worth noting that TPAO is involved in all of the significant energy projects currently being implemented in Azerbaijan. Despite the fact that Azerbaijan has signed over thirty agreements with foreign companies to develop their fields (Azeri, Chirag, Deep Water Guneshli and Shah Deniz), to date only two of them have been fully realized. In the period from 1994 to 2012, TPAO invested a total of $2.3 billion in the Azeri, Chirag and Guneshli project, and paid $650 million to the Azerbaijan budget. Overall, TPAO has invested $3.4 billion in all the projects in which it participates in Azerbaijan. The income of this company for the same period amounted to $5.4 billion. TPAO is the largest Turkish public investor in Azerbaijan.14

SOCAR’s Energy Investment in Turkey

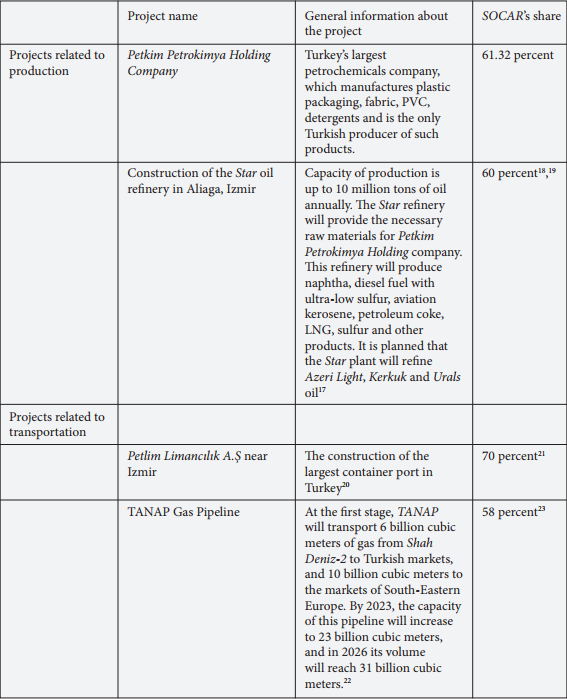

Azerbaijan’s SOCAR has also made a great contribution to the energy cooperation between the two countries. It is worth noting that the activities of SOCAR in Turkey started in the second half of the first decade of the 2000s. This is due primarily to the fact that SOCAR, in the interval following the restoration of Azerbaijan’s independence, managed to become a large international company with sufficient financial capacity and experience in implementing large projects. The company quickly became a key actor in the implementation of Azerbaijan’s geo-economic interests in the Black Sea region and the Balkans. As a consequence, to strengthen of Azerbaijan’s political and economic potential and turn the country into a leader in the South Caucasus, SOCAR’s geo-economic interests began to expand and include new regions.

The first step in the company’s vigorous activity in Turkey began in 2007, when SOCAR and the Turkish oil company Turcas signed a protocol on the establishment of a joint company. One of the milestone events in this regard was the SOCAR Turcasand Injaz alliance which acquired 51 percent of Petkim Petrokimya Holding. After some time, SOCAR acquired an additional 10.32 percent of the shares, bringing its stake in the company to 61.32 percent. Annually, Petkim Petrokimya Holding’s production covers about 25 percent of Turkey’s domestic market needs.15 Thanks to SOCAR’s investments in the joint company, its market share in Turkey stands to increase from 25 percent to 40 percent.16

Table 2: SOCAR’s Investment Activities in Turkey

In general, it is worth noting that SOCAR is the largest foreign investor in Turkey, with a future investment expected to reach $20 billion. In turn, SOCAR Energy Turkey, which is a subsidiary of SOCAR in Turkey, claims to be the largest industrial company in Turkey, whose total turnover in 2018 reached $15 billion, and in 2023 will be $30 billion.24

Energy cooperation between the two countries is developing successfully, and this success is the impetus for the further deepening of relations not only in the energy sector, but in all others. Energy cooperation is also a key factor in achieving the foreign policy goals of both countries. Mutually beneficial tandem enterprises only allow for a more successful implementation of foreign policy.

Turkish Foreign Policy Implementation in Regard to Azerbaijan

It should be noted that Turkey’s foreign policy priorities in regard to cooperation with Azerbaijan in the energy sector have changed over time. In the 1990s, Turkey’s main priorities were to ensure the market for alternative energy sources at the expense of supplies from Azerbaijan and the Central Asian countries, and turning the country into a transit country.

Currently, more than half of the gas consumed in the country is imported from only one source: Russia

Already by 2000, Turkey’s priorities regarding the energy factor in foreign policy had begun to change. Turkey’s new priorities were to establish the country as a regional leader and a regional energy hub. In principle, the desire to become an energy transit hub is a part of Turkey’s strategy of becoming a regional leader. At the same time as it works to achieve these goals, Turkey, as a country which imports energy resources, will ensure secure and sustainable access to alternative sources to meet its own domestic needs.

In general, the task of providing energy from alternative sources is a priority, and it is no accident. To date, Turkey’s economy is one of the fastest growing in the world. Along with the growth of the economy, Turkey’s energy consumption is also growing. It is expected that Turkey’s total energy demand will more than double, reaching 222.4 Mtoe by 2020. Electricity, natural gas and oil demand will reach 398-434 billion kWh, 59 BCM, and 59 million tons respectively. In short, in terms of the growth of electricity consumption, Turkey is second, after China, in the world. In the face of this growing need, Turkey’s own energy resources are scarce: from domestic production Turkey covers only 26 percent of the country’s needs, while the rest of the volume must be imported.25 Turkey currently imports about 93 percent of its oil and 97 percent of its natural gas. At the same time, Turkey is geographically located between countries where more than 72 percent of the world’s oil and gas reserves are located (in the Caspian Sea region and the Middle East), and those that use these resources (the European Union and the Western Balkans).26 Given Turkey’s domestic needs and the geopolitical significance its location, the main priorities of the energy strategy component of Turkey’s foreign policy are defined as follows:

• Diversify energy supply sources for domestic consumption;

• Increase the share of renewable and alternative sources of energy consumption;

• Begin the construction of nuclear power plants and the production of energy in them;

• Strengthen efficiency in the consumption of energy resources;

• Participate in the construction of energy transport corridors in order

to promote Europe’s energy security.27

The transformation of Turkey, first into a transit country and then into an energy hub, contributes to the construction of the necessary transport infrastructure for energy exports from Azerbaijan to Turkey, and through Turkish territory to the world markets. Thanks to the Baku-Tbilisi-Ceyhan pipeline, Turkey has become a major player in the export of oil from the Caspian Sea region to world markets. At the moment, oil from Azerbaijan is mainly supplied through this pipeline. Additionally, thanks to this pipeline, Turkey has the ability to form relationships with countries and companies in the energy sector, and with the Central Asian countries. Some amounts of oil from Kazakhstan and Turkmenistan have also begun to be transported. 3.823 million tons of Kazakh and Turkmen oil were pumped in 2014, and the transit from these countries is increasing every year. For comparison, 3.3 million tons of oil was carried in 2013, 3.048 million in 2012 and 2.237 million tons in 2011.28Over time, oil exports from these countries will continue to increase.

As for the Baku-Tbilisi-Erzurum gas pipeline, its role is more important to achieving Turkey’s economic security and the diversification of gas supplies to Turkey. It is worth noting that the problem of diversifying sources of natural gas supplies is very acute for Turkey. Currently, more than half of the gas consumed in the country is imported from only one source: Russia. Despite the need to diversify, this trend will not change in the near future. According to the forecasts of the Ministry of Energy of Turkey, the growth of gas consumption in Turkey will be 9.6 percent and will soon reach 52.2 billion cubic meters. Of this, 30 billion cubic meters of gas will be imported from Russia –in other words, almost 60 percent of consumption. As for other sources, 10 billion cubic meters will come from Iran, 6.6 billion cubic meters from Azerbaijan, and 5.6 billion cubic meters from Algeria and Nigeria as liquefied natural gas. This fact is a serious threat to Turkey’s energy security. In the case of unforeseen circumstances, if the gas supply were to be suspended in the short term, Turkey would not be able to find an alternative. Currently, around 45 percent of Turkey’s electricity generation relies on natural gas.

Given these circumstances, increasing the supply of natural gas from Azerbaijan to Turkey would provide some diversification of sources, reduce dependence on a single source, and strengthen the country’s energy security. Moreover, Turkey can be the winner in terms of the price it pays for Azerbaijani gas. It should be noted that Azerbaijani gas always costs less than the gas which is exported by Turkey’s other major suppliers, Russia and Iran. At the initial stage, the price for Azerbaijani gas was only $120 per thousand cubic meters. More recently, on January 2013, the price of gas per thousand cubic meters of gas from Azerbaijan was $350 dollars, while the cost of Russian gas was $400 and Iranian $500.29 As of January 2015, the price of Azerbaijani gas fell further, reaching $335 per thousand cubic meters. For comparison, the price of Russian gas at that time was already $425 dollars per thousand cubic meters.30 Currently, the most expensive gas is the Iranian one: Turkey pays Iran $490 per thousand cubic meters. The presence of Azerbaijani natural gas at a cheaper price allows Turkey to demand discounts from other suppliers. The mutual benefits of a decrease in gas prices was one of the main topics discussed during Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan’s meeting with Iran’s president in Iran on April 7, 2015.31 Similar claims have been filed to Russia.

Increasing the supply of natural gas from Azerbaijan will contribute to the construction of the TANAP pipeline. This project replaced the other regional project Nabucco, which has not been implemented due to various geopolitical risks, and the inability to secure supplies of natural gas from Central Asia. The difference between the two projects for Turkey is that its participation in the Nabucco project would have been limited to a transit role, meaning that Turkey could not buy gas from this pipeline. Conversely, in TANAP, Turkey serves as both a transit and an importer of Azerbaijani gas. In addition, Turkey’s share in TANAP is almost twice more than in Nabucco. While BOTAŞ had a 16.7 percent share in Nabucco, its participation in TANAP consists of 30 percent of shares. Moreover, participation in this project is also involves BOTAŞ in the expansion of the company’s experience in the implementation of such mega-projects.

The energy factor is also important in the formation of bilateral and multilateral relations. Turkey’s energy strategy should be considered in the context of the country’s new foreign policy, which began to form after the coming to power of the Justice and Development Party (AKP) in 2002. The new strategy of Turkey’s foreign policy is based on the skillful use of Turkey’s geographical position and its historical heritage. Using these two concepts as a foundation, Turkey’s foreign policy is based on the principles of “zero problems with neighbors,” the “development of relations with neighboring regions and beyond,” and the “multi-dimensional foreign policy” developed by the current Prime Minister and former Foreign Minister of Turkey, Ahmet Davutoğlu.32 Given this calculus of priorities, active cooperation in the energy sphere allows Turkey to build and improve relations with its neighbors. In this regard, Turkey’s energy transport infrastructure has played a very important role.

Turkey is transforming itself into a bridge for the formation of cooperation between the countries of the Southern Caucasus region (Azerbaijan, Georgia) and South-Eastern Europe and the Western Balkans

The TANAP pipeline strengthens Turkey’s relations with Azerbaijan and Georgia. It contributes to the formation of closer and mutually beneficial relationships with these countries, and is also a link in the chain of the implementation of new, trilateral projects. Turkey and Azerbaijan are currently developing a trilateral format of relations with Iran and Turkmenistan. Energy and transport factors play an important role here as well. Turkey intends to bring natural gas from Turkmenistan for export to European markets through the TANAP gas pipeline. Although certain aspects of this project remain unclear, Turkey and Turkmenistan reached a preliminary agreement regarding exportation to Europe during the visit of Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan to Ashgabat on November 7, 2014.33

The TANAP project will promote the development of Turkey’s relations with the South-Eastern member countries of the EU. Turkey will thus contribute to Europe’s energy security by providing an alternative transportation route for natural gas for this region. This transport project will also contribute to the formation of a new inter-regional integration process, similar to that formed between Turkey, Georgia and Azerbaijan, as part of the implementation of energy and transport projects. In the first stage, TANAP will link Azerbaijan and Turkey with Greece, Albania, Italy and Bulgaria.

In the long term, as the transportation of natural gas from Azerbaijan increases, this resource can also be delivered to other countries in the region. Already, the four countries of the Balkan region, Montenegro, Albania, Bosnia and Herzegovina, and Croatia, have signed a memorandum on cooperation in the construction of a new Ionian-Adriatic gas pipeline with a length of 530 km, which would interconnect these countries. This pipeline, with a capacity of pumping up to 5 billion cubic meters of natural gas per year, will be a branch of the TAP (Trans Adriatic Pipeline) pipeline, in order to obtain Azerbaijani gas, and reduce dependence on Russia.34 There is also the possibility of future export of Azerbaijani gas to Romania, Hungary and Austria.

Thus, on the one hand, Turkey is transforming itself into a bridge for the formation of cooperation between the countries of the Southern Caucasus region (Azerbaijan, Georgia) and South-Eastern Europe and the Western Balkans; on the other hand, it strengthens cooperation with the countries in these regions, which fully meets its foreign policy goals. At the same time, as the experience of relations between Azerbaijan, Georgia and Turkey continues in a positive light, cooperation in transport and energy projects can form the basis for the further strengthening of closer ties. In short, the TANAP project will contribute to Turkey becoming a regional energy hub.35

The energy factor has contributed to the transformation of Azerbaijan’s foreign policy from a geopolitical to a geo-economic focus

In general, it is worth emphasizing that the TANAP project allows states/consumers of natural gas to be able to purchase natural gas from alternative sources. This fact coincides with the interests of the EU, which has recently initiated the formation of an ‘Energy Union’ among its members. At the same time it should be stated that Azerbaijani gas does not compete with the supply of Russian gas to Europe. First of all, the volume of natural gas that will be delivered by Azerbaijan cannot be compared with the annual export of Russian gas to Europe, which exceeds it by more than 16 times. It is expected that in 2015, Russia will supply the EU with 166 billion cubic meters of gas.36

Thus, in its efforts to diversify, Turkey fully acts from the basis of its national interests and is not interested in unnecessary confrontation with any actor or actors in the region. In this context, Turkey is also developing a relationship with Russia in order to implement another regional project, the construction of a pipeline known as “Turkish Stream,” which will be laid under the Black Sea. Next, on the border between Turkey and Greece, a gas hub is being planned through which the gas will be sent to European countries. The total volume of “Turkish Stream” should reach 63 billion cubic meters of gas per year. This project was voiced for the first time at a press conference by Russian President Vladimir Putin on December 1, 2014, during his visit to Turkey, where he announced the termination of the project “Southern Corridor,” through which Russian gas had been planned to be supplied to European markets.37

Turkey has clearly stated that both projects are strategically important, and are not competing with each other.38 In addition, the implementation of the Turkish Stream gas pipeline remains theoretical, and will only proceed if all aspects of the project are fully negotiated, and if the project coincides with Turkey’s national interests.39 TANAP, on the other hand, is a purely geo-economic and commercial project, which is being implemented in a period of reduced oil production (and currently, falling oil prices) and is designed to improve the welfare of the citizens of Azerbaijan, and the countries in the region where the Azerbaijani gas will be supplied.

Energy Strategy as a Basis for Azerbaijan’s Foreign Policy

The main priorities for Azerbaijan’s foreign policy and national interests are to preserve and strengthen its independence, resolve the Armenian-Azerbaijani Nagorno-Karabakh conflict, liberate the occupied territories, and return the refugees and Internally Displaced Persons (IDPs) to their homes. An important factor in Azerbaijan’s foreign policy priorities is also the strengthening of the economy, and the welfare of its citizens. As in the case of Turkey, energy policy has become a key to achieving these goals. The energy factor has thus contributed to the transformation of Azerbaijan’s foreign policy from a geopolitical to a geo-economic focus.

When Azerbaijan first gained its independence in 1991, the country immediately faced a variety of political and economic problems inherited from the Soviet Union. The situation was further complicated because of the military conflict, which began because of claims to Azerbaijan by the neighboring Armenian territory of Nagorno-Karabakh. Armenia occupied Nagorno-Karabakh and seven adjacent regions. The main reason for Armenia’s military superiority over Azerbaijan in the war rested on the former’s loyalty to the regional leader, Russia. By that time, Russia had declared the “near abroad” foreign policy doctrine over the former Soviet Union countries and tried to maintain its influence in the South Caucasus region.40

A key challenge for Russia in the region was to preserve its geopolitical domination and prevent the possible presence of the West. At the same time, Russia was also trying to prevent attempts by the South Caucasus states to form closer ties with the Euro-Atlantic institutions. Russia did not have great difficulty in controlling the situation, because the West had no strategic interest in the South Caucasus region. Azerbaijan’s attempts to sign an agreement on the development of its oil fields together with Western energy companies, was regarded by Russia as a desire to integrate into the Euro-Atlantic institutions. Russia then started to consider the relationship between the two South Caucasian countries through the Armenian prism. This approach will continue, despite the fact that during President Heydar Aliyev’s reign, Azerbaijan took a more constructive position towards Russia. Aliyev made attempts towards rapprochement with Russia, but his overtures did not change Russia’s perception of the balance of power in the region. In a nutshell, Russia’s non-constructive policy towards Azerbaijan has forced the country to continue to seek contact with the West.

Azerbaijani President Aliyev clearly understood that the resolution of his country’s political and economic problems, as well as the resolution of the Nagorno Karabakh conflict, would require the consideration of many internal and external factors. As for external factors, it was necessary to involve different actors and decrease the absolute influence of Russia in the region. Only in this way would it be possible to achieve optimal conditions for Azerbaijan to resolve the Nagorno Karabakh conflict and strengthen its independence. In this case, there was only one opportunity, which was to play Azerbaijan’s trump card: energy resources. By attracting Western energy companies to operate its oil fields, much could be achieved, including the gaining of the necessary leverage to change the priorities in the foreign policies of the western states’ governments.41 This perception was not groundless. There are many examples of how energy companies eventually became detonators of foreign policy changes in their countries.

The signing of the “Contract of the Century,” was a serious success for Azerbaijani diplomacy

As a result of massive diplomatic efforts, on September 20, 1994, the “Contract of the Century” for the development of the Azeri, Chirag and Deep Water Guneshli offshore oil fields was signed in Baku. An example of Azerbaijan’s balanced policy can be shown in the fact that then president Heydar Aliyev invited the Russian energy company Lukoil to participate in the consortium along with other foreign companies, handing the company a 10 percent share of SOCAR. This move was important, because in such ways, decision makers in Russia can be divided. Having worked for many years in Moscow, Aliyev was well versed in the management system of this country. Although some groups in the Russian government were against the signing of the oil contract, Aliyev enlisted the support of Russian Prime Minister Viktor Chernomyrdin and Minister of Energy Yuri Shafrannik.

The signing of the “Contract of the Century,” in addition to its economic impact, has enormous geopolitical significance. That was a serious success for Azerbaijani diplomacy. To achieve the signing of the agreement under such difficult conditions demanded rigorous work and careful analysis. This agreement was the beginning of the formation of an independent foreign policy by Azerbaijan. At that point, western nations and institutions began to form their own interests in Azerbaijan. However, the participation of the Western energy companies in the exploitation was only the first step of the geopolitical game, according to which Azerbaijan would minimize external impacts. It was also necessary to create a transport corridor for the export of Azerbaijani oil.

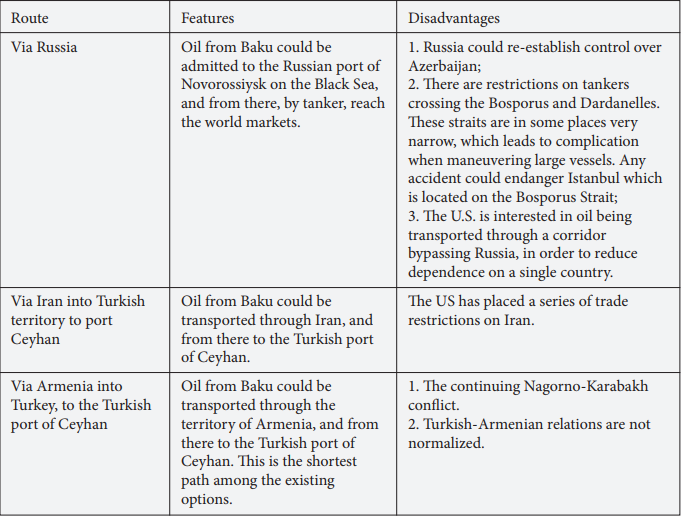

Azerbaijan is a country that has no access to the open seas and in this sense depends on its neighbors. The pipeline in the western direction could pass through several countries such as Russia, Iran, Georgia, Armenia and Turkey. Below is a table of the possible routes and their shortcomings.

Given the clear disadvantages of these routes, the only possible option was to export Azerbaijani oil to the world markets through the territory of Georgia, and from there to the Turkish port of Ceyhan. The U.S. played a very significant role in defining the routes. A start was made with the determining of the route for the export of the “early oil”42 from the Chirag oil field.43 There were two options for exportation of the early oil: the Baku-Novorossiysk pipeline and the Baku-Supsa pipeline. Both pipelines connect the Caspian Sea with the Russian (Novorossiysk) and Georgian (Supsa) ports in the Black Sea. Thus, President Clinton sent a private letter to President Aliyev, delivered by former adviser on national security, Zbigniew Brzezinski, expressing U.S. support for the construction of the Baku-Supsa pipeline.44 With the construction of the Baku-Supsa pipeline, for the first time in the post-Soviet era, one of the republics would gain access to the European markets without crossing Russian territory.45 However, Russia actively lobbied for the Baku-Novorossiysk pipeline. As a result, once again, Azerbaijan found a political solution that would neutralize possible discontent in Russia and contribute to the implementation of the wishes of the United States: it was decided to elect both corridors for the export of the early oil. It is worth noting that the U.S. has recently provided political support for the Baku-Tbilisi-Ceyhan oil pipeline as the main transport corridor for exporting Azerbaijan’s offshore oil. With its support, the U.S. provided a guaranty, in order to ensure the implementation of the project and reduce the likelihood of possible geopolitical challenges and risks.46

Azerbaijan’s savvy energy strategy has had a huge geopolitical and geo-economic impact, which remains in effect to the present day. Azerbaijan foreign policy started to be formed on the strategy that will reduce the unwanted influence of medium and big powers which have interests in the South Caucasus. Azerbaijan became a dominant power in the region; nowadays, without Azerbaijan’s participation, it is impossible to implement any regional projects. This circumstance is also the basis of the fact that Armenia has become alienated from all regional projects, becoming an outcast.

Regarding the implementation of transport corridors, it has become clear only those in which Azerbaijan is involved will succeed. Without the support of Azerbaijan in the region, no energy transport corridor can be implemented. In short, Azerbaijan’s refusal to participate in such projects as the Nabucco gas pipeline and the Trans-Caspian gas pipeline, because of their incomplete refinement and the reality of geopolitical risks, has meant that these projects have not been implemented. At the same time, Azerbaijan has independently initiated a number of transport projects, for example, the TANAP and TAP pipelines. Azerbaijan proposed that its time-tested, reliable partner Turkey should build a TANAP pipeline along Azerbaijan territory. While strengthening Azerbaijan’s already significant ties with Turkey, the TANAP project will also promote closer cooperation between Azerbaijan and the South-Eastern European states, and the Western Balkans region.

Unlike earlier energy and transport projects, which were more geopolitical in orientation, the implementation of the TANAP and TAP projects have a geo-economic and commercial context. Even in the choice between the Nabucco West or the TAP pipeline to pump Azerbaijani gas from the Turkish-Greek border, the latter received preference on the basis of economic considerations.

Following this tradition, SOCAR intends to intensify its activities in South East Europe. Thus, the company is involved in the privatization of the Greek gas transportation company, DESPA. SOCAR won a tender for the acquisition of a 66 percent stake in the company. However, SOCAR does not intend to be limited to the management of this company; based on the experience it gained in Azerbaijan and Georgia, the company wants to expand its pipeline grid to cover those regions where gasification has not yet been carried out, or is below the desired level.47

SOCAR also intends to focus on creating a gas distribution grid in Albania and Bulgaria. In Albania, this process will take place from scratch, as the country still does not use natural gas.48 As for Bulgaria, SOCAR signed a memorandum with the Bulgartransgaz Company for the expansion of an underground gas storage facility in Chiren.49 In the long term, then, as the transportation of natural gas from Azerbaijan increases, such kind of projects by SOCAR can also be implemented in other countries in the region.

The process of cooperation between Turkey and Azerbaijan is dynamic and involves a vision for future development

A successful energy policy will allow Azerbaijan to strengthen its statehood, improve the economic conditions of its citizens and become a regional leader. At the moment, the country’s energy policy also drives its foreign policy, which focuses on strengthening relationships with existing partners and contributing to the formation of new ones. This trend will contribute to the new projects that are being implemented jointly with Turkey.

Conclusion

Ensuring energy security is a key task for any country in the world today. This goal is relevant both for countries that do not have their own considerable energy sources, and for energy producers and exporters. With regard to energy cooperation between Turkey and Azerbaijan, we are faced with a successful synergy between producer and consumer. Turkey has an opportunity to purchase natural gas from Azerbaijan as an alternative source at an affordable price, while Azerbaijan has the ability to export oil and gas, both to the Turkish market, and through Turkish territory to the world markets. This mutually beneficial cooperation is very important for both countries. Moreover, the countries’ energy relations are not limited to supplies from Azerbaijan and transportation through Turkey. The two states have formed a synergy in energy relations, which has an influence on development in other areas. In this sense, the “energy factor” plays a very important role in the implementation of the foreign policies of both countries. Experience shows that cooperation between Turkey and Azerbaijan contributes to the success of their achievements. While their foreign policy priorities are different, they are not contradictory and do not compete with each other.

It is worth noting that the process of cooperation between Turkey and Azerbaijan is dynamic and involves a vision for future development. Further cooperation between Azerbaijan and Turkey in the energy sector creates the conditions for obtaining ongoing benefits for both countries. The development of major international pipeline projects will allow Turkey to become an energy hub, and receive political and economic dividends at the regional level. At the same time, Azerbaijan, in diversifying its gas supplies, has access to the European gas market. The Azerbaijani national company SOCAR will have the opportunity to invest in the region’s economy. This will allow it to strengthen its position as major international oil and gas company, and for consumers to consistently import gas from an alternative source, generate additional revenue and create new jobs.

Endnotes

- “Azerbaijan-Turkey Relations,” Official Site of Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Azerbaijan Republic, retrieved April 4, 2015, from http://www.mfa.gov.az/files/file/Azerbaijan%20-%20Turkey%20relations.pdf.

- “TANAP will Provide Significant Contributions to the Region’s Energy Supply Security and Sustainability,” Azerbaijan Today, retrieved April 4, 2015, from http://www.azerbaijantoday.az/economics3.html.

- Rovshan Ibrahimov, “Azerbaijan Energy History and Policy: From Past Till Our Days,” Rovshan Ibrahimov (ed.), Energy and Azerbaijan: History, Strategy and Cooperation, (Baku: SAM, 2013), p. 25.

- Ibid, p. 24.

- Ibid, p. 26.

- Aynur Jafarova, “TPAO ups Stake in Shah Deniz Project,” Azernews, (May 30, 2014), retrieved April 6, 2015, from http://www.azernews.az/oil_and_gas/67564.html.

- The field has not been developed to date because of a disagreement which took place between Azerbaijan and Iran on August 22, 2001. Iranian patrol boats demanded that Azerbaijan stop exploration work carried out by the BP energy company research vessel “Geophysicist 3” from the Alov, Araz and Sharq fields. Iran, which has raised its demand to own 20 percent of the Caspian Sea, believes that these deposits are located in its territorial waters. As a result, BP was forced to suspend research in these fields.

- “Yurtdışı Arama ve Üretim Faaliyetleri,” Official site of TPAO, retrieved from http://www.tpao.gov.tr/tp5/?tp=m&id=29.

- According to SOCAR’s official site, TPAO’s in this is field is 15 percent. Official Site of SOCAR, retrieved June 23, 2015, from http://socar.az/socar/az/company/production-sharing-agreements-offshore/araz-alov-sharg.

- For more information, see Rovshan Ibrahimov, “Azerbaijan’s Strategy for the Diversification of Energy Transport Routes,” İhsan Bal and Selçuk Çolakoğlu (ed.), USAK Yearbook of Politics and International Relations, Vol. 6, (Ankara: US AK, 2013), pp. 175-192.

- “Turkish Petroleum BTC Ltd. (TPBTC),” Official Site of TPAO, retrieved April 7, 2015, from http://www.tpao.gov.tr/tp2/sub_en/sub_content.aspx?id=68.

- “Baku-Tbilisi-Erzurum Gas Pipeline,” Official Site of SOCAR, retrieved June 23, 2015, from http://socar.az/socar/az/company/production-sharing-agreements-offshore/araz-alov-sharg.

- Ровшан Ибрагимов, “Энергетический Потенциал Азербайджана: Может ли Он Быть Использован Как Альтернатива России?,” Eurasian Home, (December 19, 2006), retrieved April 8, 2015, from http://www.eurasianhome.org/xml/t/expert.xml?lang=ru&nic=expert&pid=905.

- “Turkey`s TPAO Invested $3.4bn in Azeri Projects,” Azernews, (March 14, 2012), retrieved April 7, 2015, from http://www.azernews.az/oil_and_gas/42141.html.

- “ГНКАР Намерена Приобрести Нефтеперерабатывающий Завод в Европе,” news.az, September 25, 2008, retrieved April 8, 2015, from http://www.1news.az/economy/20080925104535367.html.

- Ф. Асим, “ГНКАР Собирается Приобретать НПЗ в Европе,” Zerkalo, (September 27, 2008), retrieved April 8, 2015, from http://www.zerkalo.az/rubric.php?id=36347.

- “Another Refinery to Be Built in Turkey,”Oil and Gas in Eurasia, (March 20, 2015), retrieved April 8, 2015, from https://www.oilandgaseurasia.com/en/news/another-refinery-be-built-turkey.

- Nadezhda Poltor, “SOCAR increased the share in STAR oil refinery in Turkey to 60%,” Oil and Gas,

(May 19, 2014), retrieved June 24, 2015, from http://www.rusmininfo.com/news/19-05-2014/socar-

increased-share-star-oil-refinery-turkey-60. - The remaining 40% is held by the State Oil Fund of Azerbaijan (SOFAZ).

- Эмиль Исмайлов, “Энергетический Вектор Азербайджан-Турция: от Каспия до Европы,” News.az, (March 25, 2015), retrieved April 8, 2015, from http://news.day.az/economy/565909.html.

- “Стало Известно, Когда Закончится Мегастройка SOCAR в Турции,” Day.az, (May 23, 2015), retrieved April 9, 2015, from http://news.day.az/economy/565543.html.

- Ильхам Алиев: “«Шахдениз» Является Единственным Ресурсным Источником для «Южного газового коридора»,”1news.az, (March 18, 2015), retrieved Arpil 9, 2015, from http://www.1news.az/chronicle/20150317072707068.html.

- “BP acquires 12 percent stake in TANAP pipeline project,”Anadolu Agency, (March 13, 2015), retrieved June 24, 2015, from http://www.hurriyetdailynews.com/bp-acquires-12-percent-stake-in-tanap-pipeline-project------.aspx?pageID=238&nID=79662&NewsCatID=348.

- “Энергетический вектор Азербайджан-Турция: от Каспия до Европы,” Day.az, (March 25, 2015), retrieved Arpil 9, 2015, from http://news.day.az/economy/565909.html.

- “Turkey’s Energy Strategy,” Official Site Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Turkish Republic, retrieved Arpil 10, 2015, from http://www.mfa.gov.tr/turkeys-energy-strategy.en.mfa.

- Mert Bilgin, “Energy and Turkey’s Foreign Policy: State Strategy, Regional Cooperation and Private Sector Involvement,” Turkish Policy Quartely, Vol. 9, No 2, (Summer, 2010), pp. 83-84.

- “Turkey’s Energy Strategy,” Official site Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Turkish Republic, retrieved Arpil 10, 2015, from http://www.mfa.gov.tr/turkeys-energy-strategy.en.mfa.

- “Transportation of Third Parties’ Oil via Baku-Tbilisi-Ceyhan Rises in August by 16.1%,” Abc.az, (September 6, 2014), retrieved Arpil 10, 2015, from http://abc.az/eng/news/83488.html.

- “Кубометр Азербайджанского Газа Обходится Турции на $50 Дешевле Российского,” Rosbalt, (January 11, 2013), retrieved April 8, 2015, from http://www.rosbalt.ru/exussr/2013/01/11/1080407.html.

- Александр Лабыкин, “Турция Торгуется за Российский газ,” Expert Online, (January 26, 2015), retrieved April 7, 2015, from http://expert.ru/2015/01/26/turtsiya-torguetsya-za-rossijskij-gaz/.

- “Turkey Eager to Buy More Iran Gas,” Presstv, retrieved April 7, 2015, from http://www.presstv.ir/Detail/2015/04/07/405133/Turkey-eager-to-buy-more-Iran-gas.

- Ahmet Davutoğlu, “Turkey’s Foreign Policy Vision: An Assessment of 2007,” Insight Turkey, Volume 10, No 1, (January, 2008), pp. 79-82.

- “Turkmenistan Inks Deal with Turkey to Supply gas to TANAP Pipeline,” Hurriyet Daily News, (November 7, 2014), retrieved Arpil 10, 2015, from http://www.hurriyetdailynews.com/turkmenistan-inks-deal-with-turkey-to-supply-gas-to-tanap-pipeline.aspx?pageID=238&nID=74031&NewsCatID=348.

- “Балканские Страны Построят Два Новых Газопровода,” Деловая Газета Взгляд, (May 24, 2015), retrieved Arpil 10, 2015, from http://www.russia.ru/news/economy/2013/5/24/11973.html.

- “Yıldız - Türkiye’nin Enerji Merkezi Olma Hedefi,” Haberler.com, (April 3, 2015), retrieved Arpil 10, 2015, from http://www.haberler.com/yildiz-turkiye-nin-enerji-merkezi-olma-hedefi-7154501-haberi/.

- “Экспорт «Газпрома» в Европу в 2015 году может вырасти на 10%,” Vedomosti.ru, (March 3, 2015), retrieved Arpil 10, 2015, from http://www.vedomosti.ru/business/articles/2015/04/01/eksport-gazproma-v-evropu-v-2015-g-mozhet-virasti-na-10.

- Darya Korsunskaya, “Putin Drops South Stream Gas Pipeline to EU, Courts Turkey,” Reuters, (December 1, 2014), retrieved Arpil 11, 2015, from http://www.reuters.com/article/2014/12/01/us-russia-gas-gazprom-pipeline-idUSKCN0JF30A20141201.

- “Taner Yildiz: We Need both TANAP and Turkish Stream,” News.az, (March 13, 2015), retrieved Arpil 11, 2015, from http://www.news.az/articles/economy/96373; “Yıldız: Türk Akımı ve TANAP Rakip Değil,” Bloomberg, (March 13, 2015), retrieved Arpil 11, 2015, from http://www.bloomberght.com/haberler/haber/1741411-yildiz-turk-akimi-ve-tanap-rakip-degil.

- “Yıldız - Türkiye’nin Enerji Merkezi Olma Hedefi”, Haberler.com, (April 3, 2015), retrieved Arpil 10, 2015, from http://www.haberler.com/yildiz-turkiye-nin-enerji-merkezi-olma-hedefi-7154501-haberi/.

- Michael Slobodchikoff, “Russia’s Monroe Doctrine just Worked in Ukraine,” Russia Direct, (November 21, 2013), retrieved Arpil 12, 2015, from http://www.russia-direct.org/opinion/russia%E2%80%99s-monroe-doctrine-just-worked-ukraine.

- Rovshan Ibrahimov, “Azerbaijan`s Energy History and Policy: From Past Till Our Days,” Energy and Azerbaijan: History, Strategy and Cooperation, (Baku: SAM, 2013), p. 18.

- “Early oil” refers to the crude oil produced at the Chirag oil field that did not require extra costs to build infrastructure for exploitation. It should be exported at the end of the 1990s, before the main exploitation will be started.

- Rovshan Ibrahimov, “Azerbaijan’s Energy History and Policy: From Past Till Our Days”, p. 32.

- Rovshan Ibrahimov, “U.S.-Azerbaijan Relations: A View from Baku,” Rethink Paper, No 17, (Washington DC: Rethink Institute, 2014), p. 8.

- Rovshan Ibrahimov, “Azerbaijan Energy Strategy and the Importance of the Diversification of Exported Transport Routes,” Journal of Qafqaz University, No 29, (November 29, 2010), p. 26.

- Rovshan Ibrahimov, “U.S.-Azerbaijan Relations: A View from Baku,” Rethink Paper, No 17, (Washington DC: Rethink Institute, 2014), p. 9.

- “SOCAR Obtains 66 percent Share of Greek Gas Company DESFA,” Azernews, (December 23, 2013), retrieved Arpil 13, 2015, from http://www.azernews.az/oil_and_gas/62821.html.

- “SOCAR Intends to Create First Gas Network in Albania with its Partners,” News.az, (March 9, 2015), retrieved Arpil 13, 2015, from http://www.news.az/articles/economy/96244.

- “Bulgartransgaz & SOCAR Will Conduct Joint Exploration Activities for the Expansion of the Bulgarian Underground Gas Storage,” Contact.az, (September 22, 2014), retrieved Arpil 13, 2015, from http://www.contact.az/docs/2014/Economics&Finance/092200091204en.htm#.VSeGP_msWJA.