Introduction

Elections are routinely seen as turning points in Turkey. The March 30, 2014 municipal elections were no different. All parties and civil society groups viewed these elections as turning points prior to and in the aftermath of the elections. However, few real turning points exist in Turkish electoral history. Nevertheless, a number of remarkable developments and new trends could be deduced from the results of the recent local elections.

The mining accident that took place a few weeks after the local elections, which killed 301 people and outraged the masses, may have shown the opposition that they missed an important opportunity in these elections. The influence of the living conditions of the working class and the condition of the Turkish economy on mass preferences provided some opportunity for the opposition to score highly in the elections. However, the opposition failed to capitalize on this issue and instead relied on highly polarizing issues that helped the incumbent government stay largely unaffected on an electoral basis.

Two events shaped the nature of electoral debate in the March 2014 local elections, the first of which was the Gezi Park protests that occurred about ten months prior to the local elections in May-June 2013. An isolated neighborhood protest in central Istanbul quickly turned into a massive protest movement involving millions of people all over the country.1 The Justice and Development Party (Adalet ve Kalkınma Partisi-AK Party) leadership was quick to realize the impending threat of these protests for the approaching local elections. The non-accommodating reaction of the AK Party inevitably divided and polarized the electorate. As such, the AK Party’s and the opposition’s mass support bases were consolidated and frozen, leading to very minimal electoral shifts on the basis of this issue.

Elections are routinely seen as turning points in Turkey. The March 30, 2014 municipal elections were no different

The second event came in December 2013 with graft allegations against important cabinet members of the AK Party government. This graft scandal resulted in a cabinet reshuffle within a couple of days, effectively ousting the ministers accused of corruption. In the weeks that followed, eight AK Party MPs left the party over the row. Istanbul Deputy Muhammed Çetin summed up the developments by saying that “with these corruption scandals the AK Party has turned black,” warning that there was unrest within the ranks of the party, which, at the time, was expected to lead to further resignations. The inner-party unrest and resignations remained under control during the election campaign period and did not occur to any significant degree due to the election results.2 In other words, the potential impact of the graft allegations did not materialize on the electoral front and hence the AK Party leadership was again able to consolidate its grasp over the rank and file of the party. As such, Prime Minister (PM) Recep Tayyip Erdoğan’s impending bid for the presidency was left without a popular or elite opposition within the party.

Without going into the details of the factors that set the context of these elections, I would like to underline a few of the results that came out of these elections and focus on their implications for the future presidential and general elections.

Results of the March 30, 2014 Elections

In evaluating the March 2014 local election results, it is important to keep the inherent data issues in mind when comparing these results with earlier election outcomes. The primary data problem arises because both the number and the constituency borders of Greater City Municipalities (GCMs) were changed in 2012.3 The election constituency borders of the GCMs were enlarged from urban municipal borders to include the totality of provincial borders and those in rural areas. Hence, rural inhabitants within the already existing 16 and 14 newly established GCMs were able to vote for the mayoral elections. As such, any comparison of the March 30th vote with earlier election results in these 30 provinces becomes problematic. Although the metropolitan and district mayors are elected directly via a plurality system, the metropolitan assembly is not elected, but composed of representatives of district assemblies. Those who live in a GCM vote for GCM mayoral candidates, their district mayors and district assembly representatives from political parties and cast their vote for their village or neighborhood headman (muhtar). If one wants to calculate the level of support for a political party (not mayoral candidates) then the only option is to aggregate the district assembly votes for all parties and then calculate their share within their respective GCMs. However, only using the 30 GCM mayoral votes together with general provincial assembly votes in the remaining 51 provinces would not be appropriate, as the GCM mayoral elections results are likely to be driven mostly by candidate characteristics, while the provincial general assembly vote is driven by partisan considerations.

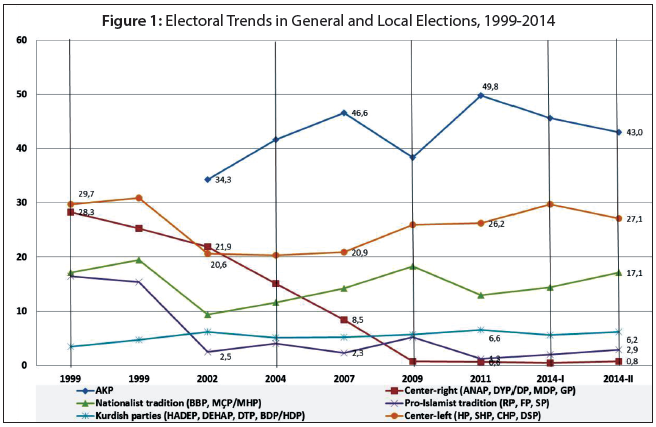

Figure 1 shows the party family’s vote shares in two different versions for the general and local elections (shown with vertical lines) since 1999. In version I (indicated as 2014-I in Figure 1), the GCM mayoral candidate’s vote shares are shown together with the provincial assembly’s vote shares in the 51 non-GCMs. In version II (shown as 2014-II in Figure 1), the GCM assembly’s vote shares are aggregated from district assembly’s votes and shown together with provincial assembly’s vote shares in 51 other provinces. The vote shares in version I is reflective of the mayoral candidate appeal and the version II vote shares are more reflective of partisan loyalties in the 30 GCMs.

This picture demonstrates that the AK Party did lose support in both versions I and II compared to 2011, but remained above its level of national support compared to 2009. With the incumbent’s drop in support, the opposition parties are on the rise. However, the opposition gains are not concentrated in a single party but rather shared between the two main opposition parties, the CHP and the MHP. For both the AK Party and the CHP, the nationwide vote share according to version I is higher than the share in version II, suggesting that the appeal of their candidates was slightly higher than their overall partisan appeal, which is more reflected in version II. We observe that the CHP’s candidate dominant vote share in version I is higher than its partisanship dominant vote share in the version II. CHP candidates in Ankara, İstanbul and İzmir appear to have performed much better than the rest of the country. When the three metropolitan results are taken out, we see that the CHP’s vote gains disappear and the MHP’s vote gains are much bolder. When we take the partisan vote calculations as reflected in the version II results, we still see that the AKP maintained nearly the same level of support, while the CHP’s level of support is indistinguishable from that of the MHP. These observations suggest that the geographic distribution of support for all parties, perhaps with the exception of the AKP, is likely to reveal significant variation.

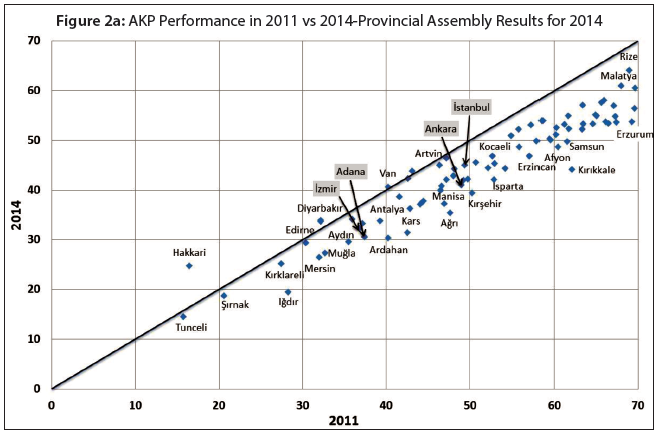

Figure 2 provides a simple depiction of the development in vote shares of three major parties from 2011 to 2014. If a party’s vote share remains below (above) the main diagonal line, which shows the equality of vote shares for that party in both 2011 and 2014, then the party in question has lost (gained) vote share from 2011 to 2014. For the AK Party (Figure 2a), we observe a loss in almost all provinces. The AK Party’s vote share increased slightly above its 2011 level in only four provinces. In most provinces, such as Rize, Aydın and Edirne, this drop is less than a few percentage points. Only in a few provinces, such as Afyon, Kırşehir and Ardahan, was there a ten point decline and only in places like Kırıkkale was there a large decline of about 20 point. In all large metropolitan provinces (Ankara, İstanbul, İzmir, Bursa and Adana) the AK Party’s vote share declined by about 4 to 7 points. Since the AK Party’s electoral support is more homogeneously distributed across regions, a regional pattern that demonstrates losses is not strikingly apparent in this picture.

For the CHP, the progression of electoral support from 2011 to 2014 appears more favorable. In about a dozen provinces, the CHP’s vote share is on the rise. However, with the exception of İzmir, this increase did not lead to a victory in 2014. In fact, despite these modest increases, we see that the level of electoral support in 2014 remains below 40 percent in all except six provinces (Eskişehir, Edirne, Muğla, Tekirdağ, Kırklareli and İzmir). The vote share of the CHP remains very low in a large number of provinces in the East and Southeastern Anatolia region. In a total of 28 provinces, the CHP obtained less than 10 percent of the vote. Of these 28 provinces, 17 are in these two regions. In places like Ağrı, Şırnak, Van, Hakkari, Şanlıurfa, Bitlis, Diyarbakır, Mardin, Batman Siirt, Muş and Bingöl, the CHP’s vote remains below 3 percent. This clearly suggests a regional narrowing of the CHP’s support to the western coastal provinces and a virtual reduction of the party to non-existence in the East and Southeastern provinces.

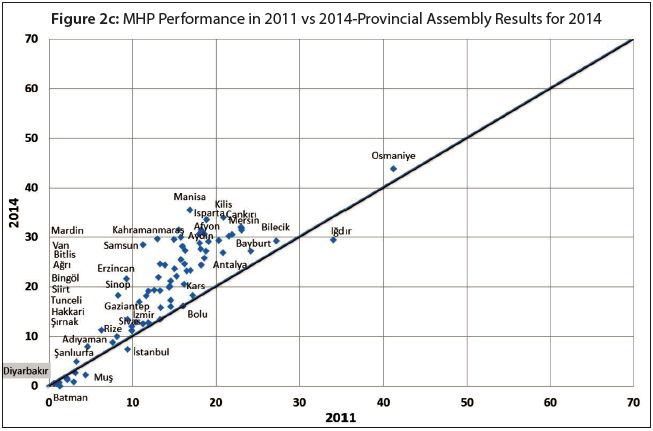

A similar observation can be made about the provincial pattern of the progression of the MHP’s support from 2011 to 2014. In Bingöl, Hakkari, Diyarbakır, Mardin, Batman, Siirt, Şırnak, Van, Ağrı, Tunceli, Muş and Bitlis, the MHP’s vote share is less than 3 percent. However, despite this low-level electoral presence in the East and Southeastern Anatolia provinces, the MHP’s vote share has significantly increased from the 2011 results in many central and western Anatolia provinces. Despite these increasing vote shares, the MHP’s level of support remains well below a winning margin for mayoral races.

The potential impact of the graft allegations did not materialize on the electoral front and hence the AK Party leadership was able to consolidate its grasp over the rank and file of the party

Was the economy behind the net losses and gains depicted above? A full treatment and testing of this expectation requires a multivariate analysis at the provincial macro-level or a micro-individual survey data. In this article, I will only present a historical depiction of economic evaluations from a series of survey data from 2002 to 2014. These evaluations are obtained in five different forms that emphasize the timeframe as well as personal vs. national conditions. From the perspective of timeframe for the evaluations, we have retrospective, prospective and present day evaluations that are then divided into personal (pocket-book) as opposed to national (sociotropic) evaluations.

In a survey conducted over the pre-election campaign period within the International Social Survey Program’s (ISSP) National Identity module, we observe a clear pattern of prioritizing economic evaluations over party choice. If an individual’s evaluation of the economy in either one of the five different versions depicted above is negative, then the likelihood of that individual casting a vote for the incumbent AK Party is significantly lower compared to those who have a positive evaluation of the economic conditions. In a similar vein, we observe that those who have a negative evaluation the likelihood of support for the opposition parties is higher.

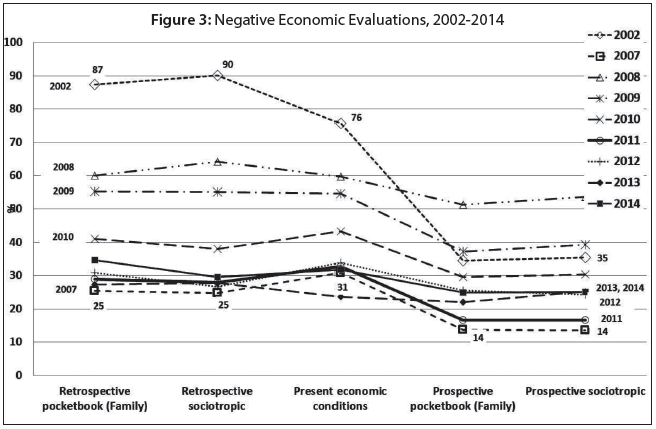

Figure 3 below shows the progression of negative economic evaluations for 2002-2014.4 This picture shows that when the AK Party came to power in 2002 retrospective economic evaluations were much more negative than the following years. A similar level of negativity was never obtained for retrospective evaluations after 2002. However, in the 2008 and 2009 global economic crisis, we observe rising negativity in these evaluations from both the retrospective as well as the prospective group. However, the AK Party government was able to control and push these negative evaluations down for the 2011 general election. Nevertheless, after the 2011 election, we observe an upward trend in negative evaluations. For two years prior to the March 2014 elections, although the level of negativity was not as high as 2008-2010, it was on the rise.

Given the state of the popular evaluations of the economy and the government’s economic policy as well as the rising allegations of corruption prior to the March 2014 local elections, a clear and simple expectation appears to have been formed on the part of the opposition. Due to the rise in people’s perceptions about the corrupt state of affairs in the incumbent government’s tenure, it is only logical that the government should lose support. However, the logic of this expectation may not work given a recent work by Klasnja and Tucker (2013), who claim that in “low-corruption” countries like Sweden where corruption is relatively rare, voters tend to punish politicians for corruption regardless of the state of the economy.5 However, in “high-corruption” countries like Moldova, where bribery and corrupt deals are relatively more prevalent, voters tend to punish politicians for corruption only when the economy is also perceived to be doing badly. Hence as the perceptions of the state of the economy improve, voters tend to be less concerned about corruption.

Although our diagnoses depicted above in Figure 3 shows that economic evaluations in 2014 were worse compared to 2011, the level of negativity may not have been high enough to warrant serious punishment, especially if the opposition did not focus on economic policy in their election campaigns. At this stage we have no systematic data concerning the opposition’s emphasis on the state of the economy. However, our subjective impression is that the opposition parties underemphasized the state of the economy and only concentrated on corruption allegations due to the assumption that it would negatively impact the government’s electoral support. Evaluations of the state of the economy were not deteriorating at a large enough pace prior to the local elections to create the expected fall in support for the AK Party.

The March 2014 local elections maintained the status quo without a serious deterioration of the AK Party’s electoral support

According to Klasnja and Tucker’s logic, corruption reduces the government’s support only when evaluations of the economy worsen. Hence, for this line of causation to work in favor the opposition, the perception of PM Erdoğan’s government as incompetent on the economic front has to settle in the minds of voters. Such a perception of incompetence did not occur on a large enough scale during the election and the AK Party held onto its electoral support without significant deterioration.

Conclusions

The March 2014 local elections maintained the status quo without a serious deterioration of the AK Party’s electoral support. One important dynamic that might be buried under the overemphasized performance of the AK Party and the CHP is the rise of the MHP. In fact, due to strategic candidate selection of other parties, which prevented the MHP from reaching its potential in large metropolitan cities, the overall vote for the MHP might not be very impressive at first glance. However, by looking at the details of the MHP’s vote share geographically, we observe a strong showing that brought the party close to the CHP in many instances.

Given the strong resistance to the AK Party government in the Gezi protests and then the break-up of the conservative coalition with the Gülen Movement over the graft allegations, the expectations that the AK Party would lose electoral support were not realized. This is partly due to continued relative strength of the economy in the eyes of the public. A complementing factor was the opposition’s weak emphasis on the AK Party’s economic performance. Despite the relative strength of mass evaluations of the economy compared to earlier years of the AK Party tenure, negative economic performance evaluations were on the rise. The opposition could have capitalized on this weakness if they continually emphasized economic policy. Both the CHP and the MHP chose not to follow that path. However, only a couple of weeks after the election, the mining disaster in Soma clearly showed that the uneasiness of the working masses presented a potent political basis of opposition. Yet, it was too late to garner any support on that basis.

However, there will be presidential election in August 2014. Perhaps, these elections will be even more consequential for the way Turkish politics will be shaped in the years to come. Not only might PM Erdoğan be a candidate for the presidency, but these elections could also be used to turn the whole political system into a presidential one. Given the relative success of the AK Party despite the difficulties it faced prior to the local elections, the AK Party candidate’s chances are obviously enhanced in the approaching presidential elections. This might be one major factor why PM Erdoğan might choose to run for president in the first place.

Turkey’s very first presidential election is likely to be shaped by partisan alignment that favors the ruling AK Party and the charisma of its leader, PM Erdoğan. Despite all the damage to Erdoğan’s image during the Gezi protests and graft allegations, he appears to continue to command firm control over his party and its popular appeal. This personal charismatic foundation of Erdoğan’s campaign for the presidential elections may invite candidates who might be tempted to follow a negative campaign against him if he chooses to run. Given the AK Party’s support and Erdoğan’s appeal among Kurdish voters, the only way a candidate could force a second round election in a presidential race would be to court voters with weak partisanship through a negative campaign. A negative campaign similar to those in the West might not be possible given the strong control and pressures over the Turkish media. The extent to which the opposition will be tempted and able to follow a negative campaign will determine the outcome of presidential elections. We will just have to wait and see how incentives and strategies are shaped during the course of the presidential election campaign.

Turkey’s very first presidential election is likely to be shaped by partisan alignment that favors the ruling AK Party and the charisma of its leader, PM Erdoğan

The state of the economy is unlikely to change drastically before August. The perceptions of the state of the economy could be targeted and pushed to the negative side if the opposition were to follow a concerted effort in this direction. Especially given the reactions to the mining disaster, such a strategy might appear more realistic. However, such a concerted effort would have to rely on a long-term strategy built on an alternative economic program with specific policy initiatives, which do not appear to be in the opposition’s electoral arsenal.

In short, given the local election results and the state of the opposition, the approaching presidential election appears to move in favor of the AK Party. Candidacy is obviously a personal as well as a party decision. PM Erdoğan’s personal charisma and the way he chooses to use this charisma during the election campaign are potent factors that will shape the outcome of elections. We will have to wait and see how political considerations and campaign strategies will shape the first presidential election in August 2014.

Endnotes

- On Gezi Park events see Y. Arat, “Violence, Resistance and Gezi Park”, International Journal of Middle East Studies, Vol. 45, No.4, (2013), pp.807-809.

- (http://www.hurriyet.com.tr/

gundem/25707298.asp) Daniel M. Kselman’s PhD dissertation at Duke University Electoral Institutions, Party Organizations, and Political Instability (2009) reports that party switching was quite common in the Turkish Grand National Assembly between 1987 and 2007. The highest rate of party switching was observed for the 19th parliamentary session between 1995 and 1999 due primarily to involuntary switches caused by party closures. However, even even without involuntary’ party switchers, the percentage of MP’s who switched parties remains far higher in sessions between 1991 to 2002 (33% in 1991-1995 session, 19% in 1995-1999, and 21% in 1999-2002) than in 2002-2007 sessions (9%) (Kselman, 2009, 177). Hence the rising resignations is a clear new sign of parliamentary instability in the making for the AK Party term. See also İ. Turan, “Changing Horses Midstream: Party Changers in the Turkish National Assembly.” Legislative Studies Quarterly, 10, (1985), 21-34. and S. Sayarı, “Non-Electoral Sources of Party System Change in Turkey”, in Essays in Honor of Ergun Özbudun, Volume 1 Political Science, (2008), pp. 399-417. - The first round of changes came in November 2012 (Law number 6360) establishing 13 new greater city municipalities (GCMs) (Aydın, Denizli, Manisa, Muğla, Hatay, Mardin, Şanlıurfa, Malatya, Van, Trabzon, Balıkesir and Tekirdağ) with a total population above 750,000 inhabitants. Then in March 2013 Ordu was added (Law number 6447) to the list of GCMs based on the argument that its population according to the population based registry syste exceeds the population limit. Yet, as of 2012 Ordu has only a population of 741,371 which further declined in 2013 (http://tuikapp.tuik.gov.tr/

adnksdagitapp/adnks.zul ). - The data for Figure 3 is from 2002, 2007 and 2011 Turkish Election Studies and the rest are from yearly ISSP surveys all co-directed by Ali Çarkoğlu and Ersin Kalaycıoğlu.

- See Marko Klasnja and Joshua A. Tucker “The economy, corruption, and the vote: Evidence from experiments in Sweden and Moldova”, Electoral Studies, 32, 3, (2013), pp. 536-543.