Introduction

“I don’t know what will happen in Iran after four years. So, I will make a plan for myself to go to America or somewhere else, like all Iranians want to. But I know I will not be able to do that, because you need to have money (….) So I said to myself: ‘Ok I will not be able to go to other countries, so I have two options: to stay in Turkey, or to go back to Iran.” (Farzad, 25, Iranian student at Boğaziçi University in Istanbul, Turkey)

The phenomenon of transit migration has become a central element in both scholarly and policy discussions since in the 1990s, when the European Union introduced stricter border controls and imposed serious obstacles for legal migration into its territory.1 As a consequence, more migrants from the East and the South seemed to use overland and maritime routes in order to reach Europe and had to use several “stop-overs” on the way, such as Turkey, Ukraine, Libya, Egypt and Morocco. At the same time, large inflows of migrants and asylum seekers from the South and East have transformed these so-called ‘transit countries’ into immigration countries in their own right.2 However, few studies have investigated the settlement of migrants in locales that they only intended to transit. This article will try to fill part of that gap by presenting the stories of several Iranian migrants for whom the perception of Turkey transformed from a transit location into a place of immigration. What factors were important in their decision to settle down in Turkey, and how can we relate that to Turkey’s changing modes of reception for foreigners from the Middle East?

Migrants often change their intentions and routes based on the conditions that they find in the transit country, which are influenced by various factors

Secondly, I will show how current flows of Iranian students to Turkey are connected to Turkey’s development into a regional educational hub for an increasing number of students from the Middle East and Central Asia.3 The limited research done on this topic shows that some of these students would actually prefer to study in Europe or America, but their inability to do so led them to opt for Turkey as a “second best choice”.4 This article will discuss to what extent we can compare Iranian students at Turkish universities with other Iranian migrants that originally arrived to Turkey with the intention of transiting.

In the next section, I will shortly discuss the theoretical framework on transit migration and student mobility, followed by a brief historical overview of Iranian transit migration to Turkey. Afterward, I will present the findings from my fieldwork with a focus on two groups: those Iranians who first had their mind set on a Western country but eventually settled down in Turkey, and those Iranians who came to Turkey in the context of education.

Theoretical Framework: Transit Migration and Student Mobility

The concept of transit migration emerged in the 1990s, when stricter migration policies in the EU and other Western states induced people to take more dangerous routes to reach their destination or travel through a range of third countries in the vicinity of the EU. This attracted a lot of attention from international policy makers, NGO’s and scholars.5 However, in recent years, the concept of transit migration has been thoroughly criticized as well. For example on the basis of the flawed assumption that migrants in transit zones always want to move on to Europe.6

On a theoretical level, the concept of transit migration is very difficult to grasp and it is even more challenging to define who a “transit migrant” is. According to Papadoupoulou (2008), transit migration is a phase in the migration process “that cuts across various migrant categories and all migrants may find themselves in the condition of transit at some point.” An additional difficulty lies in the fact that a migrant’s ultimate destination is not always known from the outset and usually develops while ‘in transit.’7 Migrants often change their intentions and routes based on the conditions that they find in the transit country, which are influenced by various factors, such as policy changes and migrants’ perception of risks related with onward movement. The variability of these conditions can also result in migrants’ decision to settle down in what was originally only seen as a transit country.8 Therefore, it is not always possible to perceive the journey of a migrant simply as a movement from A (the origin) to B (the destination), but the phase in between A and B is of crucial importance for the outcome of the journey.9

Furthermore, the concept of transit migration is often associated with irregular migration and human smuggling, while many migratory movements (such as migration from Iran to Turkey) actually consist of mixed flows and include asylum seekers, refugees and legal labor migrants as well.10 Nevertheless, it has been observed that for migrants with higher levels of education and financial resources, it is easier to cross borders and thus their time spent in transit is shorter.11 As such, it is very important to conduct research on higher educated migrants, such as students, who find themselves in a “transit phase” within their larger migration process. Such studies have been rather scarce until now.

One of the exceptions is formed by Berriane (2009), who did research on Sub-Saharan African students in Morocco and connected them to other (transit) migrants in the country. He found that the overwhelming majority (82 percent) of Sub-Saharan students intended to move on to Europe or North America after graduation, instead of returning back home.12 In the case of Australia, Ghim Thye Tan showed that 21 percent of Chinese and Indian students wanted to migrate onwards to another country, usually the UK or the United States.13 Lastly, studies suggest that also Russia is used as an important transit route for students. Since the 1990’s, many individuals from countries in Asia, Africa and the Middle East arrived to Russia with student visas and hoped to move on to Western European countries.14

In recent decades, the rising importance of the global knowledge economy has actually led to an enormous expansion in international student mobility towards OECD countries. In addition to the increase in the number of international students worldwide (from 800.000 students in 1975 to 4.3 million in 2011,15 there is also a significant proportion of students do not return home and transform from ‘students’ into ‘migrants.’16 This development is facilitated and sometimes even encouraged by Western governments, which need highly skilled migrants in order to fill up certain labor shortages in the economy.17 At the same time, the tuition fees of international student present much-needed additional income for universities that are faced with increasing privatization.18 Moreover, in light of the restrictions on the mobility of low-skilled and irregular migrants, using the “educational channel” often becomes the only legal possibility for young people from developing societies to move to other countries.19

The attraction of international students has also become an important issue for universities in Turkey, as they are trying to keep up with the internationalization of education in the context of decreasing state funding.20 As a result, the number of foreign students in Turkey has more than quadrupled from 10,000 students in 2000 to 45,000 students in 2014.21 Turkey has been particularly active in recruiting students from Central Asia, the Caucasus and the Middle East. For these students, Turkey’s geographical and cultural proximity, low subsistence costs and Westernized system of education are important pull-factors.22 However, up until now, there have been no studies that investigate what happens after international students in Turkey graduate. For example, do most of them return to their home country, find a job in Turkey or move onwards to another nation? One study by Tekelioğlu et al. on 80 foreign medicine students in Ankara suggests that there is definitely a possibility that a proportion of foreign students will settle down in Turkey: in their survey, 48 percent of the students considered staying in Turkey after graduation.23

Iranian Migration to the West via Turkey: A Background

In order to contextualize the movement of Iranian students to Turkey, it is important to look at the broader history of Iranian migration to Western countries. This movement really took off in the 1960s and 1970s, when many wealthy Iranians went abroad to study in the United States.24 However, the 1979 Islamic Revolution caused unprecedented numbers of Iranians to flee their home country in the face of increasing political oppression, censorship and human rights abuses.25 In general, it is accepted that the outflow of Iranian migrants in the 1980s was of a more political nature, while Iranian migrants after 1990 had more economic incentives to leave.26 Despite the mix of political, economic and social reasons to leave, many Iranians chose the “asylum route” and eventually obtained refugee status in the West.27

That many young, educated Iranians left Iran after the 1999 student protests and the 2009 ‘Green Movement,’ often using Turkey as a transit stop

Currently the majority of Iranians abroad reside in the United States, while the remainder can be found in other Western countries such as Canada, Germany and Sweden.28 It is important to note that a large proportion of the Iranians living abroad are generally well-educated, causing a significant and persisting brain drain in Iran. There are several factors that suggest that this “academic exodus” will continue in the next few years. For instance, Iran has a disproportionally young population, a severe lack of good-quality higher education and a general absence of academic freedom. Iran’s constrained economy and isolation from other markets has led to high youth unemployment rates of 25-30 percent, leaving many young university graduates without good job prospects.29

These social and economic factors are exacerbated by the restrictive political climate in Iran. It is presumed, for example, that many young, educated Iranians left Iran after the 1999 student protests and the 2009 ‘Green Movement,’ often using Turkey as a transit stop.30 In any case, it seems that Iranians’ reasons for leaving their home country result from a complex mix of economic and political motives – whether they move as students, asylum seekers, irregular migrants, tourists or legal labor migrants.

Turkey as a Transit Migration Hub for Iranians

It is estimated that since 1979 the majority of the Iranians who went westwards used Turkey as a transit route.31 Mirroring the general pattern of Iranians moving to Western countries, Iranians’ passage through Turkey is heavily characterized by “mixed flows” of asylum seekers, irregular migrants and legal migrants. For most of these groups, Turkey is the most logical exit out of Iran, thanks to Turkey’s visa exemption for Iranian citizens and the long and loosely secured Iranian-Turkish border that facilitates human smuggling and irregular crossings.32

Until the 1990s, many Iranians perceived Turkey merely as a transit route and not as a destination country, partly due to the fact that Turkey adopted a “laissez-passer” attitude and encouraged the overwhelming majority of Iranian migrants and asylum seekers to move on to third countries.33 In addition, the Turkish government does not recognize Iranians and other asylum seekers from outside Europe as refugees, due to its geographical limitation in the 1951 UN Geneva Convention. As the UNHCR in Turkey only started to offer a systematic resettlement program for asylum seekers from the Middle East after 1986, we can assume that in the 1980s, many Iranians traveled further to Western countries and applied for asylum there.34

According to scholars there is a small group of 10,000 Iranians that failed to transit to a Western country in the 1980s and 1990s and mostly live in Turkey undocumented

However, since the 1994 Turkish asylum regulation, a two-tiered system was introduced in cooperation with the UNHCR that gave the Turkish government more control over the influx of asylum seekers. As a result, a growing number of Iranians have applied for asylum with the UNHCR in Turkey and have been resettled to Western countries.35 Nevertheless, not all asylum claims are accepted, and resettlement procedures can take up to several years. As a result, some asylum seekers live in liminal and precarious conditions for long periods of time, while others gradually settle down in Turkey.36 Rejected asylum seekers and other Iranians who choose not to apply for asylum in Turkey sometimes try to find an irregular passage to other countries and lodge their asylum applications elsewhere, a process whereby asylum seekers are turned into “irregular transit migrants.”37

A Statistical Profile of Iranians in Turkey

Despite all the contextual evidence, there are very few accurate statistics available on the numbers of Iranian migrants that have passed through Turkey in recent decades, and estimates vary from half a million to 1.5 million.38 We can nevertheless combine some statistics in order to get an image of the size of Iranian migration to Turkey.

In terms of asylum seekers and refugees, Iranians filed a total of 30,689 asylum applications with the UNHCR in Turkey between 2001 and 2012.39 Between 1995 and 2010, Iranians constituted the largest group of asylum seekers in Turkey, responsible for 45.8 percent of all applicants, closely followed by Iraqis (39.2 percent). Iranians generally had a high recognition rate, with 61.4 percent of all applications accepted and the majority resettled in Western countries, such as the U.S. (46 percent), Canada (22 percent) and Scandinavia (17 percent).40

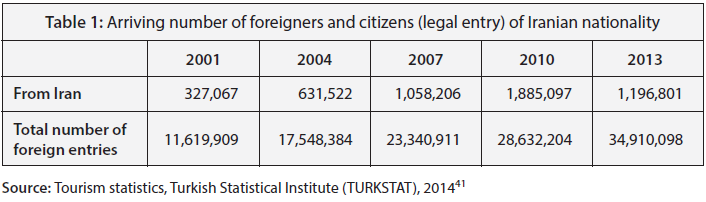

We can also see a significant increase in the number of Iranians entering Turkey legally over the last decade, with the 327,000 legal entries in 2001 increasing threefold to almost 1.2 million in 2013. From 2007 onwards, the number of Iranians entering Turkey started to surpass one million on an annual basis. However, these statistics comprise all legal entries by Iranian citizens, including tourists, merchants, students, asylum seekers and individuals that plan to use to Turkey as a transit route to another country.

At the same time, there seems to be a growing settled Iranian community in Turkey, although official statistics are incomplete and rather outdated. Nevertheless, census data indicate that Iranians were among the top 13 new immigrant groups in Turkey between 1995 and 2000 and belonged to the top 13 of foreigners in possession of a work permit in 2011.44 In addition, between 2000 and 2004 Iranians were the third largest group in Turkey that obtained citizenship through regular acquisition, directly following Bulgarians and Greek ‘heimatloss.’45 However, as the academic literature on Iranian migration to Turkey mainly focuses on transit migrants and asylum seekers, there are very few indicators of a “settled” Iranian community. According to scholars like Kirişci and İçduygu, there is a small group of 10,000 Iranians that failed to transit to a Western country in the 1980s and 1990s and mostly live in Turkey undocumented.46 Nonetheless, findings by Danış (2006), as well as my own fieldwork from 2009, illustrate that many of these ‘failed migrants’ did acquire legal status or even Turkish citizenship. Most of them were educated middle class Iranians and often of Azerbaijani-Turkish background, making it easier for this group to acquire Turkish citizenship thanks to the Settlement Law of 1934.47

From “Transit” to “Settlement”? Empirical Findings on Iranian Migrants and Their Choice of Turkey

The aim of this chapter is to focus on Iranian migrants that have stayed in Turkey for a long period of time and show signs of settlement in the country. This group of migrants is formed by the “small residue” of a larger flow of Iranian transit migrants in the 1980s and 1990s and more recent groups of Iranian migrants that often came to Turkey to study. In this chapter, I will first outline the methodology used and subsequently give a small overview of the Iranians that I interviewed in terms of their migration trajectories and their views toward staying in Turkey.

Methodology

The empirical findings presented in this article are the result of three months of fieldwork in Turkey and the Netherlands in 2009. The research was conducted as part of a Master’s thesis project that was qualitative and, due to the limited number of studies on the topic, exploratory in nature. In addition to a literature review and interviews with a number of organizations and institutions in the field, I conducted 19 semi-structured interviews with Iranians who were living or had lived in Turkey in either a regular or irregular manner between 1987 and 2009. I have stayed in touch with most of these respondents and paid them follow-up visits in 2013-2014.

Most interviews took place in Istanbul and Ankara and were conducted in either English, Dutch, Persian or Turkish. Respondents were found through a combination of organizations in the field, my own personal network of Iranians and Turks in Turkey and the Netherlands, and snowballing methods. The sample included 15 Iranians of (partly) Azerbaijani origin (78 percent), as they seemed to be overrepresented in Turkey thanks to linguistic and cultural similarities and their easier reception by the Turkish host population.

Moreover, as I was a university student myself, the snowballing method probably led to the inclusion of a higher number of (PhD) students and graduates, who were living in major urban centers in Turkey. Although there were also a high number of Iranian asylum seekers awaiting the outcome of their procedure in one of Turkey’s “satellite cities,” I did not include these asylum seekers in my sample. Finally, the sample is male-dominated as it was more difficult to find an equal number of Iranian men and women living in Turkey at that time.

Although the empirical research dates from 2009, since then there have been almost no studies on Iranian migrants in Turkey, while most research focuses on asylum seekers.48 This research therefore reveals important patterns on Iranian (transit) migration to Turkey that are still valid today.

Migration Trajectories

In total, I conducted interviews with 19 Iranians that had either lived or were living in Turkey. Half of these respondents came to Turkey for the purpose of transit. Four of them had passed irregularly through Turkey in the 1980s and 1990s and were eventually accepted as refugees in the Netherlands, where I met and interviewed them. Three people came to Turkey during the same period with the intention of transiting to a Western country, but they eventually settled down in Turkey. Two people had been in Turkey for only 10 months and considered themselves to be “in transit.” The second half of the respondents came to Turkey with a stronger intention to stay, at least for a while: one woman migrated to Turkey to join her partner already living there, and two men came to work. The remainder consisted of seven people who came to Turkey with the intention to study or to do a PhD.

Almost all the respondents stated that they originally did not have the intention to move to Turkey for a long time, either because they perceived Western countries as their ultimate destination

The Iranians in my sample had diverse and mixed motivations to leave Iran: seven migrants mentioned that they had been forced to leave Iran because they had an altercation with the police, four of them eventually obtained refugee status in Europe, and the other three chose to study or do a PhD in Turkey. The other 14 Iranians mentioned that they had left Iran in search of better opportunities and to enjoy more academic, political, social or cultural freedom.

The respondents also held various ideas about their intended length of stay in Turkey and possible onward movement, which seemed to change over time and could by no means be called “definite.” Therefore, it is challenging to categorize the individuals in my sample as “transit migrant,” “refugee” or “irregular migrant,” as many of them fell into various categories throughout their entire migration process. In terms of their intended destinations, most respondents in the sample mentioned Canada, the U.S. or various European countries as their original goal. Most believed that they could find better educational and work opportunities and more cultural and political freedom there. They saw the West as a place “where human rights are respected and everyone is taken care of.”49

Iranians Arriving in Turkey in the 1980s and 1990s

Almost all the respondents stated that they originally did not have the intention to move to Turkey for a long time, either because they perceived Western countries as their ultimate destination or because they hoped to return to Iran when the political situation improved. Nevertheless, all the respondents mentioned the geographical proximity of Turkey to Iran as an almost “logical” factor in their decision to migrate to or via Turkey. Especially the Azerbaijani-Iranian students that I interviewed noted the cultural and linguistic closeness between the two countries as an important factor in their choice of Turkey.50 However, there are some interesting differences in the perception of Turkey for various groups of migrants and this influenced their decision to stay or to move on. It is possible to identify two groups who both arrived to Turkey in the late 1980s and 1990s: the transit migrants that passed through Turkey irregularly and obtained refugee status in the Netherlands; and the migrants that came to Turkey with the purpose of transit but eventually settled down.

For many migrants in transit, it is often a combination of their financial resources, the possibility to work en route, possession of travel documents and the reliability of their social contacts that facilitates their onward journey

The first group – the four transit migrants that settled down in the Netherlands – all mentioned that they had never considered staying in Turkey and always had their minds set on moving onward to a Western country. Most of them perceived Turkish society as conservative and thought that Turkish people experienced the same lack of cultural freedoms and human rights as the people in Iran. For them, Turkey was merely a transit route because they lived in constant fear of the police and did not see applying for asylum in Turkey as a viable option – as expressed by Sattar, who transited illegally through Turkey in 1999:

“If someone would have done that (apply for asylum in Turkey) they would have sent them back (to Iran). There was an agreement between the Iranian government and Turkey to send back, deport Iranians immediately. That’s why I never tried that.” (Sattar)

This pattern seems to be in line with Jefroudi, who notes that in the 1980s and 1990s, the UNHCR did not systematically accept and resettle refugees in Turkey and a portion of them were deported back to Iran.51 Therefore, we can infer that those migrants that were forced to leave Iran did not feel comfortable applying for asylum in Turkey, as it was so “close” to Iran. Besides, their negative perception of Turkey was an important factor that augmented their motivation to move on to the West.

Secondly, my sample included three respondents who solely came to Turkey with the purpose of transit, but decided to stay in Turkey shortly after their arrival. These Iranians had been living in Turkey for a long while at the time of the interview (i.e., 13, 22 and 23 years). Below, I will focus on three respondents from my sample, who all stated that there original destination was a Western country but that their plans changed when they arrived in Turkey. Meryem (49) followed her husband to Turkey, and envisioned the country merely as a step-on-the-way towards Canada. However, when she arrived there with her children, her husband stated that he liked Turkey and he wanted to stay here, and Meryem complied. Setareh (27) came with her mother to Turkey with the plan to move to Sweden from there, as Setareh’s uncle was living there as a refugee. Unfortunately, after a few months it became clear that the uncle was not in a position to help bring them over to Sweden, so they stayed in Turkey and Setareh’s mother went back to school. Finally, Faramarz (43) came to Turkey to transit to Canada and spoke to several smugglers that could help him get there. However, he did not consider any smuggler to be reliable. From his nephew who was living in Turkey, he heard about the possibilities to study in Turkey and decided to stay and go back to school. After four years, Faramarz brought over his wife Mina from Iran, and he has been working and living in Ankara for the last 13 years.

Thus, it seems that the Iranians in my sample who have been residing in Turkey for the longest period of time can be considered a “small residue” from the large flow of Iranians that passed through Turkey in the 1980s and 1990s. Should these cases be viewed as “failed transit migrants” because they lacked the necessary financial resources or social contacts to overcome the legal obstacles in their passage to the West?

For many migrants in transit, it is often a combination of their financial resources, the possibility to work en route, possession of travel documents and the reliability of their social contacts that facilitates their onward journey.52 In addition, someone’s socioeconomic position also influences the amount of risk a migrant would have to take in order to cross borders irregularly.53 This was very clear in the case of Faramarz, who renounced moving onwards in an irregular way and simultaneously perceived Turkey as a country where he could lead a comfortable life. We can therefore argue that these migrants stayed and settled down in Turkey because they viewed Turkey as a “second best option” and preferred it over returning to Iran.

However, it should be noted that these three settled migrants – Meryem, Faramarz and Setareh – did not leave Iran because of political persecution and therefore did not consider it a problem to remain in a country so close to home. This is in contrast to the transit migrants who traveled on to the Netherlands: they mentioned a constant fear of deportation in Turkey and were thus willing to take more risks to reach Europe in an irregular way. Considering the estimated one million Iranians that moved on to the West in the 1980s and 1990s, this group of approximately 10,000 Iranian migrants who settled down in Turkey are likely to be the exception to the rule. Nevertheless, as the border restrictions and entry regulations of the European Union and other Western countries continue to become stricter, it is likely that an increasing number of Iranian migrants will refrain from taking further risks to move onwards and choose to prolong their stay in Turkey.

“Academic Migration” to Turkey After 2000

Based on my research findings, it is also possible to identify a new pattern of more academically-inclined migration from Iran to Turkey, especially since the 2000s. My sample consisted of seven Iranian males who came to Turkey to study or do a PhD: three people were more or less forced to leave Iran because of their political activities and/or because they were unable to study or teach at university. More than half of the sample deliberately chose to study in Turkey and not a Western country and had been living in Turkey for eight to 10 years. They did not have any concrete plans to move to another country, although they did hope to return to Iran one day if the situation improved. Here I will shortly discuss the trajectories of four (PhD) students: Farzad, Arash, Hossein and Ashkan.

“Before, when I was 16, my father just organized to send me to Germany. Most of our family members are in Germany, America, etc. And we had good connections there, everything was fine, but in the goodbye part I just cried, I said: ‘No I am so young, I have to stay here.’ And my father said: Yeah, you are too young, so you have to stay more and move to a country nearby Iran so we can just come and see you.’ So we chose Turkey.” (Farzad, 25, graduate student in Istanbul)

Farzad is an interesting example of an Iranian student who had the opportunity to move to a Western country, but decided to study in Turkey. In Farzad’s case, his parents orchestrated for him to leave Iran for various reasons, such as evading military service and having an “easy exit” in case his family wanted to get out of Iran. Due to Farzad’s young age, he chose to stay close to Iran so his family could visit him now and then. Farzad studied International Trade at Boğaziçi University in Istanbul, where he still lives today.

The three other Iranian students in my sample mentioned explicitly that they had the chance to go to Western countries too, but they intentionally decided to move to Turkey. Thirty-year-old PhD-student Hossein had been increasingly confronted with the lack of academic and political freedom in Iran, and was eventually banned from his university. He therefore decided to leave Iran and pursue his academic career elsewhere. Hossein had been accepted at universities in the UK and the U.S., but wanted to stay close to his family and preferred to live in Turkey, a country that was culturally more like Iran. Ashkan, a 27-year-old PhD-student, had applied to universities in Europe and Canada as well, but had to leave Iran suddenly to avoid military service and chose Turkey as a quick and easy to reach destination. PhD-student Arash (38) left Iran after being arrested for his political activities and came to Turkey as a student. However, after two years he discovered he was unable to return to Iran and decided to apply for asylum with the UNHCR in Turkey. He was resettled to Canada several years later, but returned to Turkey because he wanted to be more closely involved in his political and cultural activities for Iran. Especially in the case of Arash, we can see how the distinction between ‘refugee’ and ‘academic migrant’ is often blurred and changes over time.

Furthermore, it is important to note that the three PhD students mentioned above already had (academic) contacts in Turkey. Moreover, as they belonged to the Azerbaijani minority in Iran, they were already familiar with Turkey’s language and culture. Thus, their stories challenge the assumption that migrants from outside the EU always want to move to Europe. Instead, they often prefer to go to a country culturally and geographically close to their own.

The geographical proximity and cultural similarities between Turkey and Iran make Turkey a convenient hide-out to escape the daily limitations of Iranian society, while staying close to home at the same time

Finally, most of the Iranian students in my sample did not know if they wanted to stay in Turkey, move back to Iran or migrate to another country in the future. Despite this, there also seemed to be clear signs of “settlement” among them: some respondents had brought over their wives from Iran and applied for Turkish citizenship. During the time of the research, Farzad still had a plan in the back of his mind to go to Canada or Europe, but he also accommodated himself to life in Turkey and adapted his career on the basis of that. Farzad still lives and works in Turkey today. The same goes for Hossein, who deliberately chose to go to Turkey and not to a Western country. In the cases of these students, we can see how academic mobility can transform into more permanent forms of migration and settlement.

Nevertheless, it should be mentioned that I only conducted interviews with students that were still in Turkey at the time of the research. To get a more accurate picture of how Iranian students might use Turkey as a springboard to Western countries, just like other Iranian transit migrants and asylum seekers in earlier decades, research should also be done among students who studied in Turkey and moved on to another (Western) country afterward. This phenomenon is the subject of my ongoing research.

Discussion and Conclusion

In this article, I demonstrated that Turkey played a crucial role as a transit country for Iranian migrants and asylum seekers in the 1980s and 1990s. However, over the course of time, several factors have caused a drastic change in Turkey’s position towards migrants. First of all, the EU’s increasingly restrictive policies have made direct legal entry into Europe more difficult, leading migrants to take higher risks, changing their trajectory, or prolonging their stay in a non-EU country. Because of its’ candidacy for EU membership, Turkey is also being pressured to increase its own border controls and fight against irregular migration, thereby making previous seemingly “laissez faire” practices towards migrants more difficult.54 This development might increase the likelihood that migrants who are attempting to move on to Europe may find themselves unable to do so. What is more, instead of returning back home, they might opt to stay in Turkey.

Migrants’ increased propensity to stay in Turkey should be seen in the light of Turkey’s changed attitude towards foreigners in recent decades. During the earlier period of Iranian migration to Turkey in the 1980s and 1990s, for example, stories of police harassment and fear of deportation abounded. This allegedly caused many Iranians who fled their home country for more political reasons to move onwards to other countries. Nevertheless, there was also a small group of Iranians who were generally looking for a better life and found a legal pathway to stay in Turkey, although they were the minority.

For the Turkish government, the mobility of highly educated Iranian students is a more desired form of migration for several reasons. Accepting foreign students from Iran does not only mean a much-needed additional source of income for Turkish universities, but student mobility is also much less politically sensitive than the reception of Iranian asylum seekers. However, although Turkey expects the influx of Iranian students to be temporary, this study has shown that there is a likelihood that Iranian students might not return after graduation, but gradually end up staying in Turkey. The geographical proximity and cultural similarities between Turkey and Iran make Turkey a convenient hide-out to escape the daily limitations of Iranian society, while staying close to home at the same time.

Although this is a subject that needs more research than I have been able to do in this article, student mobility from Iran does points to a potentially significant factor in Turkey’s gradual transition from a sending and transit-country into a country of immigration. Turkey’s system of higher education might be thereby be an increasingly important channel which Iranians use to leave their home country behind and move on to a new life with better opportunities.

Endnotes

- Michael Collyer, Franck Düvell and Hein de Haas, “Critical Approaches to Transit Migration”, Population, Space and Place. Vol. 18, No. 4. (2012), p. 407.

- Franck Düvell, “Crossing the Fringes of Europe: Transit Migration in the EU’s Neighbourhood. COMPAS Working Paper No. 33, 2006, University of Oxford, p. 9, 11-12; Ahmet İçduygu & Deniz Yükseker, “Rethinking Transit Migration in Turkey: Reality and Re-presentation in the Creation of a Migratory Phenomenon,” Population, Space and Place, Vol. 18, No. 4 (2012). p. 442.

- Hanife Akar, “Globalization and its Challenges for Developing Countries: the Case of Turkish Higher Education,” Asia Pacific Education Review, Vol. 11 No. 3, (2009), p. 452; Ayhan Kaya, “Turkey as an Emerging Destination Country for Immigration: Challenges and Prospects for the Future,” Joachim Fritz-Vannahme and Armando Garcia Schmidt (eds) Europe, Turkey and the Mediterranean: Fostering Cooperation and Strengthening Relations, (Gütersloh: Bertelsmann Foundation, 2012), p. 88.

- Farkhad Alimukhamedov, “Understanding Socio-economic Situation of International Students at Turkish Universities,” 10th TurkMiS Workshop, Ankara, Hacettepe University, 2014.

- Franck Düvell, “Transit Migration: A Blurred and Politicised Concept,” Population, Space and Place, Vol. 18, No. 4, 2012, p. 416; Aspasia Papadoupoulou, “Exploring the Asylum-migration Nexus: a Case Study of Transit Migrants in Europe”. Global Migration Perspectives no. 23. Geneva: Global Commission on International Migration, 2005, p. 3-4.

- Sylvie Bredeloup, “Sahara Transit: Times, Spaces, People,” Population, Space and Place, Vol. 18, No. 4; Collyer et al., “Critical Approaches to Transit Migration”; İçduygu & Yükseker, “Rethinking Transit Migration in Turkey”.

- Aspasia Papadoupoulou, “Transit migration through Greece,” (Irregular) Transit Migration in the European space: Theory, Politics and Research Methodology, Koç University, Istanbul, Turkey, April 2008, p. 1-2, 7.

- Marieke Wissink, Franck Düvell & Anouke van Eerdewijk, “Dynamic Migration Intentions and the Impact of Socio-Institutional Environments: A Transit Migration Hub in Turkey.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration studies, Vol. 39, No. 7, 2013, p. 1088, 1102.

- Joris Schapendonk, “Turbulent trajectories: African Migrants on Their Way to the European Union.” Societies, Vol. 2, 2012, p. 38-39.

- İçduygu & Yükseker, “Rethinking Transit Migration in Turkey”, p. 443; Papadoupoulou, “Transit migration through Greece,” p. 7.

- Düvell, “Transit Migration: A Blurred and Politicised Concept,” p. 417, 422-423.

- Johara Berriane, “Les Etudiants Subsahariens au Maroc: des Migrants parmi d’Autres?” Méditerranée, No. 113, 2009, p. 149.

- Ghim Thye Tan, “The transnational migration strategies of Chinese and Indian students in Australia,” unpublished PhD thesis, University of Adelaide, 2012, p. 200-202.

- IOM, “Transit Migration in the Russian Federation,” IOM Migration Information Programme, Budapest: International Organization for Migration, 1994 ; Irina Ivakhnyuk, “Transit migration through Russia,” (Irregular) Transit Migration in the European Space: Theory, Politics, and Research Methodology. Koç University, Istanbul, Turkey, April 2008, p. 15.

- OECD, “Education at a Glance 2013,” OECD Indicators, OECD Publishing, 2013, p. 306.

- For studies on Australia, see G.T. Tan “The transnational migration strategies of Chinese and Indian students in Australia.”; Michiel Baas, “Imagined Mobility: migration and transnationalism among Indian students in Australia,” unpublished PhD thesis, University of Amsterdam, 2009. For studies on Japan; Grazia Liu-Farrer, “Educationally Channeled International Labor Mobility: Contemporary Student Migration from China to Japan.” International migration review, Vol. 43, No. 1, 2009; and for the United States: Heike C. Alberts and Helen D Hazen, “There are always two voices…”: International Students’ Intentions to Stay in the United States or Return to their Home Countries,” International Migration, Vol. 43, No. 3, 2005.

- Ana Mosneaga, “Student Migration at the Global Trijuncture of Higher Education, Competition for Talent and Migration Management,” G. Tejada et al. (eds.) Indian Skilled Migration and Development, Dynamics of Asian Development, (India: Springer, 2014), p. 97.

- Shanthi Robertson, “Transnational Student-Migrants and the State: The Education-Migration Nexus,” (Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2013), p.18-19.

- Karine Tremblay, “Academic mobility and immigration,” Journal of Studies in International Education, Vol. 9, No. 3, 2005, p. 197.

- Akar, “Globalization and its Challenges for Developing Countries,” p. 447-448

- Alimukhamedov, “Understanding Socio-economic Situation of International Students at Turkish Universities”

- Akar, “Globalization and its Challenges for Developing Countries,” p. 449, 452; Mahmut Özer, “Türkiye’de Uluslararası Öğrenciler”, Yüksek Öğretim ve Bilim Dergisi, Vol. 2, No. 1, 2012, p. 11-12; S.Tekelioğlu, H. Başer, M.Örtlek, and C. Aydinli, “Uluslararası Öğrencilerin Ülke ve Üniversite Seçiminde Etkili Faktörler: Vakıf Üniversitesi Örneği.” Organizasyon ve Yonetim Bilimler Dergisi, Vol. 4, No. 2, 2012, p. 197.

- Tekelioğlu et al, ““Uluslararası Öğrencilerin Ülke ve Üniversite Seçiminde Etkili Faktörler,” p. 195.

- Halleh Ghorashi, “Ways to Survive, Battles to Win: Iranian Women Exiles in the Netherlands and United States, “ (New York: Nova Science Publishers, 2002), p. 53-54; Akbar E. Torbat, “The Brain Drain from Iran to the United States,” The Middle East Journal, Vol.56, No. 2, (Spring 2002), p. 277.

- Şebnem Köşer-Akçapar, “Conversion as a Migration Strategy in a Transit Country: Iranian Shiites Becoming Christiansin Turkey,” International Migration Review, Vol. 40, No. 4 (Winter 2006), p. 822.

- Maral Jefroudi “Migration Across the Turkish-Iranian Border,” N.Ö. Baklacioğlu and Y. Özer (eds.) Migration, Asylum, and Refugees in Turkey: Studies in the Control of Population at the Southeastern Borders of the EU, (Lewiston: Edwin Mellen Press, 2014), p. 325-326.

- Şebnem Köşer-Akçapar, “Re-Thinking Migrants’ Networks and Social Capital: A Case Study of Iranians in Turkey,” International Migration, Vol. 48, No. 2, 2010, p. 164.

- Mehdi Bozorgmehr and Daniel Douglas, “Success(ion): Second-Generation Iranian Americans,” Iranian Studies, Vol. 44, No. 1, 2011: 13; Ghorashi, “Ways to Survive”, p. 111.

- Mohammad Chaichian, “The new phase of globalization and brain drain: Migration of educated and skilled Iranians to the United States”, International Journal of Social Economics, Vol. 39 No. 1, 2011, p. 22-25.

- Ibid, 19; Jefroudi, Migration Across the Turkish-Iranian Border,” p. 318.

- Ahmet İçduygu, “Irregular Migration in Turkey,” IOM Migration Research Series (Geneva, 2003), p.17.

- Joanna Apap, Sergio Carrera & Kemal Kirişci, K. “Turkey in the EU Area of Freedom, Security and Justice,” EU-Turkey Working Papers 3, Centre for European Policy Studies (CEPS), 2004, p. 27.

- İçduygu, “Irregular Migration in Turkey,” p. 21.

- Ghorashi, “Ways to Survive”, p. 111.

- İçduygu, “Irregular Migration in Turkey,” p. 58-59.

- For accounts on Iranians in these conditions, see Didem Danis, “Integration in Limbo. Iraqi, Afghan, Maghrebi and Iranian Migrantsin Istanbul. MiReKoc research report (Istanbul: 2006); Köşer-Akçapar, “Conversion as a Migration Strategy in a Transit Country”; and Zahide Özge Biner, “Transit refugees: Legalization struggles of Iranian asylum seekers in Van, Eastern Turkey,” unpublished doctoral thesis, University of Strasbourg, 2012.

- İçduygu and Yükseker, “ Rethinking transit migration in Turkey”, p. 448-449.

- İçduygu, “Irregular Migration in Turkey,” p. 21; Danış, “Integration in Limbo,” p.16.

- “Displacement: The New 21st Century Challenge,” UNHCR Global Trends report 2012, retrieved on May 12th, 2014 from http://unhcr.org/

globaltrendsjune2013/ - Kemal Kirişci, “ Turkey’s New Draft Law on Asylum: What to Make of It?” S. P. Elitok and T. Straubhaar (eds) Turkey, Migration and the EU: Potentials, Challenges and Opportunities. (Hamburg: Hamburg University Press, 2012), p. 70-72.

- Turkish Statistical Institute, Tourism Statistics, 2014, retrieved on May 15th 2014 from http://www.turkstat.gov.tr/

PreTablo.do?alt_id=1072 - Apap et al, “”Turkey in the EU Area of Freedom, Security and Justice,” p. 27.

- Kaya, “Turkey as an Emerging Destination Country for Immigration,” p. 88-89; Danış, “Integration in Limbo,” p. 119-121.

- Turkish Statistical Institute, “Immigration statistics 2000”, retrieved on May 15th 2014 from http://www.turkstat.gov.tr/

VeriBilgi.do?alt_id=1067 ; Turkish Ministry of Labour and Social Security, “Labour statistics: work permits of foreigners, 2011.” Retrieved on May 13th 2014 from http://www.csgb.gov.tr/ csgbPortal/csgb.portal?page= istatistik - General Directorate of population and citizenship, Ankara.

- Kemal Kirişci, “Disaggregating Turkish citizenship and immigration practices,” Middle Eastern Studies, Vol. 36, No. 3, 2000, p. 11-12; İçduygu, “Irregular Migration in Turkey,” p. 21.

- Danış, “Integration in Limbo,” p. 116.

- See Köşer-Akçapar, “Conversion as a Migration Strategy in a Transit Country”, and Zahide Özge Biner, “Transit refugees”

- Wissink et al, “Dynamic Migration Intentions,” p. 1094.

- Richard Perkins and Eric Neumayer, “Geographies of educational mobilities: exploring the uneven flows of international students,” The Geographical Journal, Vol. 180, No. 3, 2014, p. 251-252.

- Jefroudi, “Migration Across the Turkish-Iranian Border,” p. 330

- Düvell, “Crossing the Fringes of Europe”, p. 13; Joris Schapendonk, “Turbulent Trajectories: Sub-Saharan African Migrants Heading North.” Unpublished PhD thesis, Radboud University Nijmegen, 2011, p. 123-124.

- Wissink et al., “Dynamic Migration Intentions,” p. 1094.

- İçduygu and Yükseker, “ Rethinking transit migration in Turkey”, p. 452.