Introduction

Health has been at the forefront of the radical transformations undertaken by the AK Party during their 15 years in power to date. The AK Party was established in 2001, it has won all of the elections since the November 2002 general election, and has now been in power for 15 years. In 2002, the AK Party introduced its general reform framework, the Emergency Action Program (EAP),1 and its health reform plan, the Health Transformation Program (HTP),2 which is a health sector policy based on the EAP. Since its implementation in 2003, access to health services has improved, community health status indicators have improved, the level of satisfaction with health services has increased, and citizens have been protected from financial risks.

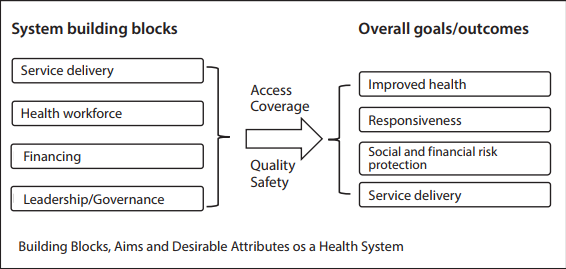

This article evaluates the 15 years of leadership of the AK Party in terms of health and health policies using the Health System Framework of the WHO. Many frameworks can be used to assess health systems, reforms or policies; these frameworks are similar and include the functions of a health system, that is, its building blocks. In addition to building blocks, the Health System Framework of the WHO includes the objectives and results of a health system (Figure 1). In conducting the present analysis, the WHO framework has been preferred for this reason.

Figure 1: The WHO Health System Framework

Source: Adopted from WHO3

First, the historical process and background of Turkey’s health policies will be presented. Second, the 15 years of leadership of the AK Party will be assessed in terms of health and health policies using the framework shown in Figure 1. Within this framework, the transformation of the building blocks (service delivery, financing, labor, management, and leadership) of the health system over the period of these 15 years will be explained and evaluated. Subsequently, the impact of these changes on the goals and outcomes (health improvements, fulfilment of expectations, protection from financial risks, and system sustainability) of the health system will be described and evaluated. Finally, the results and recommendations of the study will be presented.

Historical Process and Background of Turkish Health Policies

Notably, the roots of the contemporary Turkish health care system can be traced back to the Tanzimat Reforms (1839). However, the institutionalization and organization of the health system, with regard to the legal, physical and human resources of today, were established by the Ministry of Health (MoH) using limited resources in May 1920.4 The MoH initially focused on the legislation for and restructuring of the health system after the Independence War. The foundations of the present public health system were established between 1923 and 1946. Over this period, laws were enacted to govern the tasks and functions of the MoH, which is responsible for the planning, organization and implementation of health programs, including preventive public health programs and programs to control communicable diseases such as tuberculosis, malaria and leprosy. Over this period, the health system was organized “vertically.” Diagnosis and treatment centers were established in the districts, and fully functioning hospitals were opened in provinces such as Ankara, Diyarbakır, Erzurum, and Sivas.5

Between 1980 and 2002, Turkey granted citizens the constitutional right to access social insurance and health services

Over the period from 1946 to 1960, health centers were established to provide integrated health services to the Turkish community. Additionally, all hospitals were transferred from local administration to the MoH. The Social Insurance Institution (SII) was created in 1946 to provide health insurance for blue-collar workers in the private and public health sector.6

In 1961, Law No. 224 on the Socialization of Health Services was enacted6 and it was the basis for the establishment of national health services. Notably, this law mandates that health services must be provided continuously and meet the needs of the people. This law provided health services to all citizens for free, or partially free, at the point of use. The aim was to develop infrastructure to expand health services, including preventive and environmental health services and health education, throughout the country, and to make access to the infrastructure easy. The concept of health centers was expanded to include health centers in rural areas as well as district hospitals. However, the large capital investments required for the expansion were absent. Most fiduciary resources were allocated to personnel costs instead of infrastructure, medical equipment and other assets required for the provision of health services.7

Health programs based on the Law on the Socialization of Health Services were included in the First Five-Year Development Plan, which was a result of the 1960 military coup. Discussions regarding General Health Insurance (GHI) began in the 1960s and lasted for years.8 In 1971, the GHI Act, which supported universal health insurance, was submitted to the Turkish General National Assembly (TGNA) but was subsequently rejected. In 1974, the law was again put before the Parliament but was never addressed. In 1978, a law governing the full-time study of public health practitioners was adopted, and doctors were banned from working in the private health sector. In 1980, a new law was introduced that abolished the previous law. This act allowed physicians and other health personnel to work in the health sector part-time, primarily in the private health sector.9

For 15 years following the passage of the 1961 law, although countrywide socialized health services had been planned, the plan was not implemented. However, in 1983, health coverage for the entire country was announced. Until the 1980s, Turkish health policy was based on the Law on the Socialization of Health Services. Notably, a basic health care system had been established throughout Turkey within the scope of the Law. Historically, the health system reforms of this period are considered “the first wave of health reforms.”10

In September of 1980, there was another military coup in Turkey. This led to a new era in the Turkish economic and political system and created a health service process characterized primarily by liberalization and deregulation. The primary role of the state shifted from health service provision to the regulation or facilitation of health services. The role of the private health sector increased, especially its provision of health services.11

Between 1980 and 2002, Turkey granted citizens the constitutional right to access social insurance and health services. Per the 1982 Constitution, all citizens have a right to social security, and the state must provide social insurance for all citizens. Additionally, the Constitution contains provisions that strengthen the role of the state in the regulation of health services, as well as those services related to the implementation of GHI.

Between 1986 and 1989, the government enacted the Basic Health Services Act and the Bağ-Kur Health Insurance Launching Act. The Basic Health Services Act governed access to and equity of health services and aimed to correct the deficiencies of the 1960 Integrated Health Care System. It aimed to increase the financing of the health sector, based on the Basic Health Services Act, because one reason for the failure of the Integrated Health Services System was financial resource constraints. However, the success of the Basic Law was limited. Neither laws that would support systemic health reforms nor a comprehensive health policy had been adopted. Efforts to stimulate the health sector had also been absent.6

Until the early years of the 2000s, almost no reforms were implemented. Initiatives were stymied by structural problems, such as political instability, economic instability, lack of a democratic culture, the opposition of interest groups, and inadequate social support

Between 1988 and 1993, the MoH and the State Planning Organization (SPO) conducted a major health reform study to assess the needs of the health system and identify methods for its reform. Because of the findings, the National Health Policy was adopted in 1990, which governed the implementation of GHI and family medicine. This policy described health system objectives and delineated health system priorities, such as maternal health.12 Based on this, a National Health Policy Document was introduced, which included recommendations for health system reforms and their definitions.13

During the First National Health Congress, held in 1992, the initiation of GHI implementation was revisited, but no progress was made. However, in the same year, the Green Card Program was launched, which was a step towards meeting the health system expenditures of the uninsured population. Between 1993 and 1997, there were six different Health Ministers, and the health system policy was unstable.14

In November 2000 and February 2001, Turkey encountered a major economic crisis. Its currency was devalued by more than 100 percent, inflation was 68 percent, and the economy shrank by 8 percent. As the unemployment rate increased, the economic crisis resulted in poverty that affected access to the health system and social services. Food and monetary inflation made even economically stable households vulnerable to poverty. The most significant impact on the health sector was a decline in the number of registered insured persons and an increase in the number of Green Card holders.6 The health reforms of this period are the “second wave of health reforms.”15

Until the early years of the 2000s, almost no reforms were implemented. Initiatives were stymied by structural problems, such as political instability (e.g., coalition governments), economic instability (e.g., economic crises), lack of a democratic culture, the opposition of interest groups, and inadequate social support. These elements led to a failure to enact and enforce health reforms over this period.16

The AK Party captured the majority of parliamentary seats in the November 2002 general elections and formed a single-party government that supported European Union (EU) accession negotiations, the World Bank (WB) and the International Monetary Fund (IMF). The AK Party introduced its general reform framework, the EAP,17 and its health reform plan, the HTP,18 which is a health sector policy based on the EAP. The EAP and HTP addressed the primary issues of the health sector and all elements of the health system (such as funding, service delivery, management and organization).19

The HTP aimed to organize, finance and provide effective, efficient and well-organized health services. The basic principles of the HTP are being human-centric and sustainable, implementing continuous quality improvement, participation, reconciliation, volunteerism, the separation of powers, decentralization, and competitiveness of services. Taking these principles as a framework, the basic components of the HTP were developed. They include designating the MoH as the controller and planner of Turkey’s health programs. Additionally, General Health Insurance includes everyone in a single policy. Moreover, it strengthened primary health care and family medicine; effective and staged referral chains; health enterprises that have financial and administrative autonomy; health employees that are knowledgeable, competent and highly motivated; education and science institutions that support the system; the quality and accreditation of qualified and effective health services; the institutional structure for the management of rational medicine and equipment; and access to quality information during the decision-making process.20

Notably, the Turkish health system began a significant process of change under the HTP. Historically, the HTP can be described as the third wave of Turkish health reforms. It differs from the first and the second wave in that the health reform initiatives of the HTP reached the legislative stage, have gradually been implemented, and resulted in change. The implementation of the second phase of HTP began in the last quarter of 2016.

Evaluation of 15 Years of the AK Party in Terms of Health and Health Policies

In this section, the 15-year period of AK Party governance is analyzed and evaluated in terms of health and health policies. The analysis includes two complementary elements, the primary components of the health system and the objectives of the health system, which are depicted by the framework shown in Figure 1.

The budget allocated for preventive and primary health services in 2002 was 928 million TL, which will increase to 12 billion 706 million TL in 2017

Basic Components of the Health System

Health Services Provision

The Turkish provision of health services includes a public-private mixed structure, of which the public health sector is predominant. Many actors provide preventive, curative and rehabilitative health services as well as the promotion of health services. Among the primary service providers are the MoH, university hospitals and the private sector. The MoH is the primary provider of primary and secondary health care and, additionally, is the sole provider of preventive health care. The MoH runs large-scale healthcare facilities, such as hospitals, clinics, family health centers, community health centers, dispensaries, etc. Although university hospitals, by definition, are theoretically required to provide only third-level health services, in practice, they offer most health care services. The private health sector provides health services through hospitals, clinics and outpatient clinics, examination rooms, pharmacies, laboratories, medical devices, and pharmaceutical companies. Additionally, religious groups, minorities and foundations can provide health services.21

Notably, public health services have improved over the past fifteen years. Compared to that of 2002, the 2016 budget allocation for preventive and primary health care (using 2016 figures) increased nominally by 12 times and by 4.6 times in real terms. Additionally, the budget allocated for preventive and primary health services in 2002 was 928 million TL, which will increase to 12 billion 706 million TL in 2017.22

Moreover, vaccination services, provided for free, have significantly increased and both fifth and triple vaccination rates have increased from 80 percent in 2002 to 97 percent in 2016. For the first time in the world, to increase quality, the Electronic Vaccine Tracking and Cold Chain Monitoring System are being implemented, which use a data code to track and monitor vaccinations.23

Maternal and child health services have also improved. Prenatal care services increased from 70 percent in 2002 to 99 percent in 2016; the birth rate in health institutions increased from 75 percent in 2002 to 99 percent in 2016; the number of visits per infant increased from 3.4 in 2002 to 8.2 in 2016, and the number of baby-friendly hospitals rose from 141 in 2002 to 1,200 in 2016. However, caesarean section rates remain high, which can have negative consequences for both maternal and child health as well as health expenditures. Caesarean section rates have shown a decreasing trend in state hospitals in recent years but an increasing trend in university hospitals, especially in private hospitals.24

Approximately three million Syrian refugees, who have been housed temporarily for humanitarian reasons, have been provided with free health services, and Immigrant Health Centers have been established so that the Syrian people can access health services more easily

Furthermore, more than ten Healthy Life Culture Incentive Programs have been launched within the coverage of the HTP, including the Tobacco Control Program. In addition, approximately three million Syrian refugees, who have been housed temporarily for humanitarian reasons, have been provided with free health services, and Immigrant Health Centers have been established so that the Syrian people can access health services more easily.25

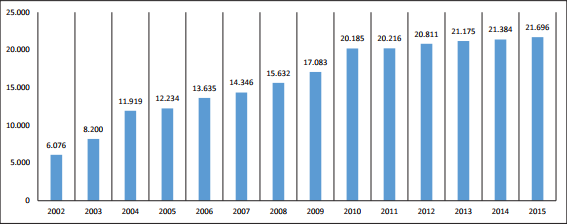

In 2005, Turkey initiated the practice of family medicine within the scope of the HTP. In 2010, the family medicine practice was expanded to the entire country. Turkey aims to strengthen primary health care services using the family medicine model and to establish a health services structure that has authority and control over other health service levels. The number of family health center examination rooms per year is shown in Graph 1. The number of examination rooms, which was 6,076 in 2002, increased by more than 300 percent to 21,696 in 2015 (Graph 1).

Graph 1: Number of Family Health Center Examination Rooms

Source: General Directorate of Health Research (SAGEM)26

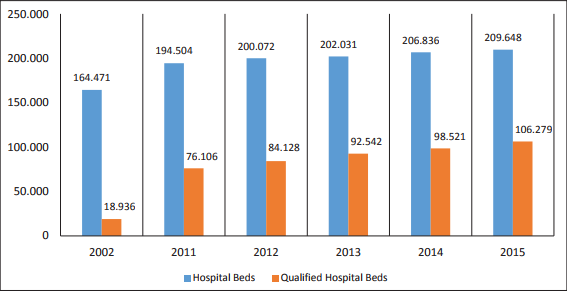

Measured per year and sector, the number of hospitals increased by approximately one third between 2002 and 2015. Additionally, as shown in Graph 2, the number of hospital beds increased. Among these increases, the ratio of qualified hospital beds was approximately 10 percent in 2002 and increased to 60 percent in 2015.

Graph 2: Hospital Beds and Number of Qualified Hospital Beds

Source: General Directorate of Health Research (SAGEM)27

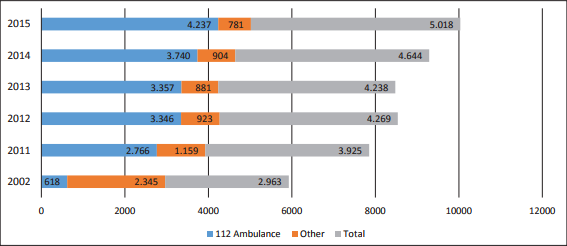

Turkish emergency health services have increased the number of fully equipped 112 emergency ambulances from 618 at the end of 2002 to 4,237 in 2015. The number of 112 emergency stations increased from 481 in 2002 to 2,600 over the following fifteen years. In addition, snow-track ambulances, motorcycle emergency response teams, and air and sea ambulance systems have also been put into service (Figure 3).

Graph 3: Number of Ambulances, Ministry of Health

Source: General Directorate of Health Research (SAGEM)28

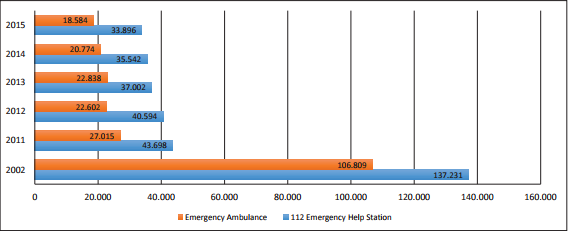

From 2002 to 2015, there has been a decreasing trend in the number of people per emergency aid ambulance and 112 Emergency aid stations (Graph 4).

Graph 4: Population Number per Emergency Ambulance and 112 Emergency Aid Stations, Ministry of Health

Source: General Directorate of Health Research (SAGEM)29

In addition to providing health services during disasters and emergencies, 8,068 health personnel, including 81 specialists, were trained within the scope of the National Medical Rescue Squads (UMKE). A total of ten mobile hospital units were built, each of which include 30 beds, an operating theatre and an imaging unit. In addition, emergency medical services have been provided abroad. The Center for Emergency Health Education Project (ASEP) provided 24 group-training sessions (serving 361 health personnel) in Niger, Albania, the Republic of Kosovo, Hungary, the Republic of Macedonia, Lebanon, Kyrgyzstan, Mongolia, Benin-Ivory Coast, Azerbaijan, Tajikistan, Gambia, and Ethiopia.30

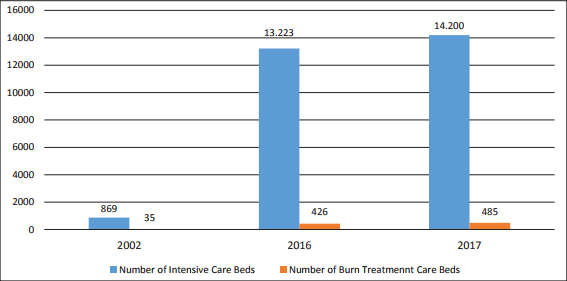

Additionally, there have been significant increases in the number of intensive care beds and burn-treatment beds (Graph 5).

Graph 5: Number of Intensive Care and Burn-Treatment Beds

Source: Akdağ31

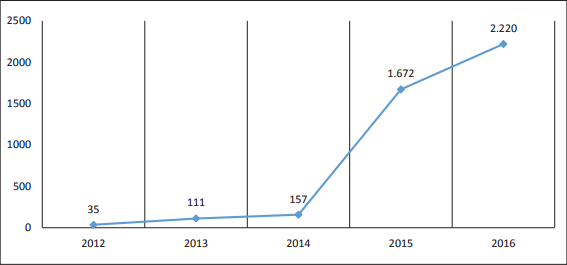

Because of the ageing population and an increase in chronic diseases, the need for long-term care has increased steadily, as have the number of long-term care beds (Graph 6).

Graph 6: Number of Long-Term Care Beds

Source: Akdağ32

Additionally, significant improvements were made to oral and dental health services, medical technology capacities and organ transplant services. Moreover, the Turkish Stem Cell Coordination Center (TÜRKÖK) project was developed. Furthermore, a patient rights unit was established in all hospitals affiliated with the Ministry of Health, and patients were granted the right to choose a doctor. The Ministry of Health Communication Centre (SABİM) replies to an average of 7,000 communications daily. Turkey also provides health services in many countries, including Sudan, Somalia and Palestine.33

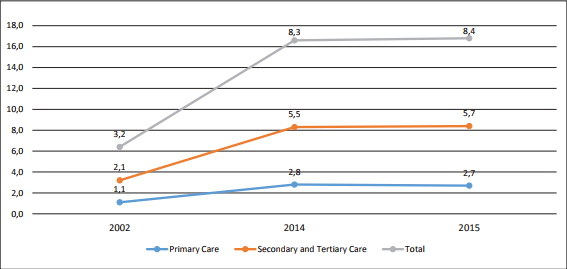

Graph 7: Number of Doctor Consultations per Capita

Source: Akdağ34

In Turkey, during the 15-year period under review here, there has been a significant increase in the number of visits to a physician per person. The average number of times per year that an individual visited a physician increased from 3.2 times in 2002 to 8.4 in 2015. It is assumed that some of this increase is due to the increased scope of and access to health services that resulted from the HTP. However, although not empirically studied, observations have suggested that the high increase in per capita medical claims is unnecessary. It would be useful to investigate this in the future (Graph 7).

Human Resources for Health Care

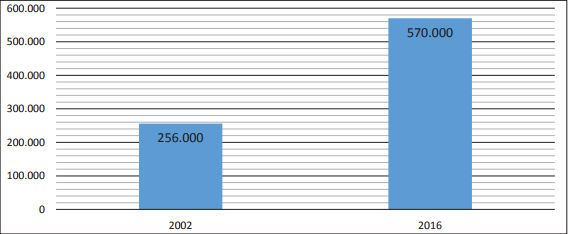

The health care workforce forms the center of any health system. Developing quality human resources with sufficient capacity is the primary means for achieving the goals of health systems.35 Turkey has made significant improvements to its health workforce over the last 15 years. The total number health care employees was 256,000 in 2002 and increased to 570,000 in 2016 (Graph 8).

Graph 8: Change in Human Resources for Health Care

Source: Akdağ36

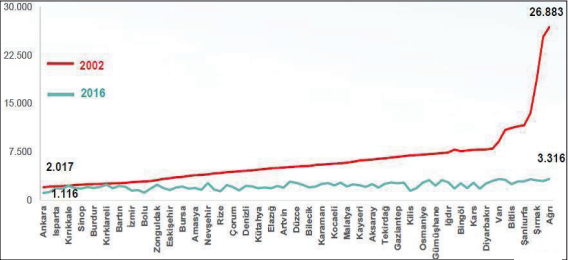

Graph 9: Population per Medical Specialist Employed by the MoH (December 2002-October 2016)

Source: Akdağ38

There have been positive developments in the distribution of human resources in a fair and balanced manner throughout the country. The ratio between the province with the highest population per medical specialist and the province with the lowest population per medical specialist was 1/13 in December 2002 and 1/3 in October 2016 (Graph 9).37

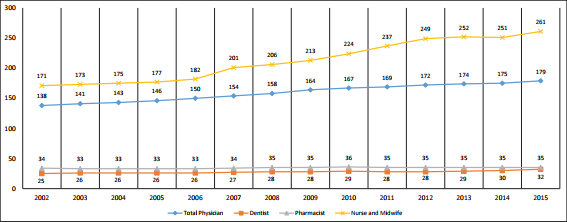

The number of physicians, dentists, pharmacists, nurses and midwives per 100,000 people per year are shown in Graph 10. Although there was no significant increase in the number of dentists and pharmacists, there was a significant increase in the number of physicians and nurses.

Graph 10: Physicians, Dentists, Pharmacists, Nurses and Midwifes per 100,000 People in All Sectors

Source: General Directorate of Health Research (SAGEM)39

Health Financing

Until 2006, the financial system of the Turkish health system did not balance costs among patients and was fragmented and managed by multiple systems (such as SII, Bağ-Kur, the Retirement Fund, Active Officers and the Green Card programs). However, in 2006, health care financing institutions were consolidated through the Health Transformation and Social Security Reform (SDSGR), the Social Security Institution (SSI) and the GHI Act. Currently, the GHI program within the SSI provides health insurance for the population, primarily through social premium fees. The GHI program aimed to solve the problems that were due to a fragmented financial system, to provide a guarantee of universal health coverage and to consolidate health insurance programs.40

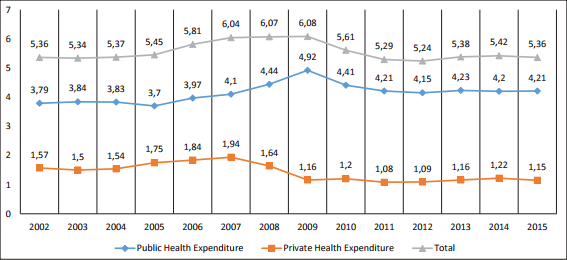

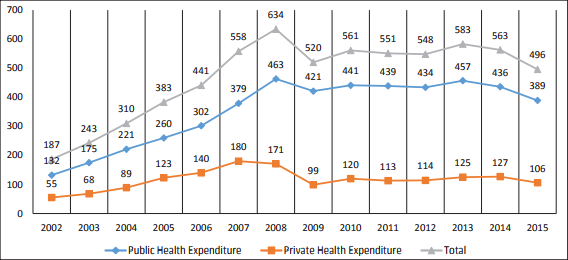

The 2015 ratio of total health expenditures to the GDP was equal to that of 2002. However, public spending in terms of GDP increased slightly, while private health expenditures decreased slightly (Graph 11).

Public and private health spending per capita has shown an increasing trend. In 2002, public health expenditures per capita were $132; they increased to $389 in 2015 (Graph 12).

Graph 11: Public and Private Expenditures on Health (% GDP)

Source: General Directorate of Health Research41

Graph 12: Public and Private Health Expenditures, $ per Capita

Source: General Directorate of Health Research42

Graph 13: Proportion of Out-of-Pocket Health Expenditures to Total Health Expenditures (%)

Source: General Directorate of Health Research43

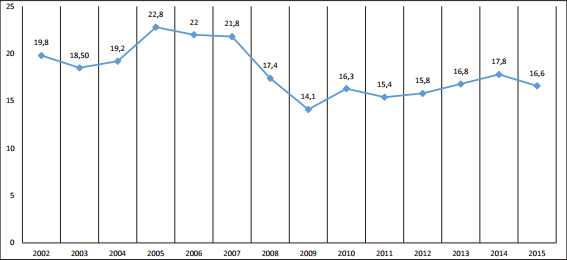

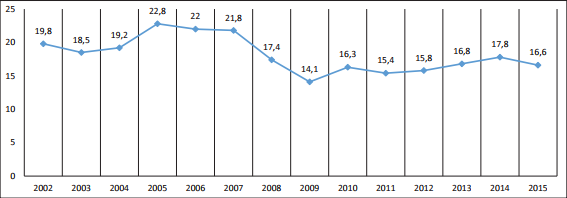

The ratio of out-of-pocket health expenditures to total health expenditures decreased from 19.8 percent in 2002 to 16.6 percent in 2015 (Graph 13).

The performance of any health system, health policies or health reform programs are evaluated using four basic parameters, including improvements in health indicators, protection of citizens from financial risks, patient satisfaction with health services, and the sustainability of the health system

Leadership and Governance

There are many actors in the Turkish health management and health policymaking processes. The state fulfils its basic responsibilities for planning, coordination, financial support, and the development of health institutions through organizations such as the Ministry of National Education, the Ministry of Family and Social Policy, the Ministry of Development, the Higher Education Council, the Ministry of Labor and Social Security, the Ministry of Finance, the Ministry of National Education and other institutions, in particular the Ministry of Health. Trade unions, professional organizations and other non-governmental organizations also contribute to the process of establishing a health policy. In addition, international institutions and organizations, such as the WHO, WB, OECD, IMF, and WTO, health technology companies (primarily pharmaceutical and medical device companies) and transnational organizations, such as the EU, are directly or indirectly involved in shaping Turkey’s health policies.44

The mission of the MoH, in accordance with the Decree on the Organization and Duties of the Ministry of Health and its Affiliates, is to ensure that everyone lives in a state of complete physical, mental and social well-being. Within this framework, the MoH manages the health care system and determines policies regarding 1) the protection and development of public health and the reduction and prevention of diseases, 2) the implementation of diagnostic, treatment and rehabilitative health services, 3) the prevention of the introduction of internationally recognized public health risks into the country, 4) the development of health education and research activities, 5) the provision of safe and high quality medicines that are used in health services; specialty products; substances subject to national and international control; drugs and auxiliary substances used in pharmaceutical production; cosmetics and medical devices on the market that are to be delivered to the public and the determination of their prices, 6) the provision of equitable, high-quality and efficient service through the conservation of human and material resources and increased efficiency, ensuring a balanced distribution of healthcare related human resources across the country and cooperation among stakeholders, and 7) plans for health institutions operated by public and private legal entities and individuals.45

Results of the Implementation of the Health Transformation Program

As shown above, the AK Party government has transformed and improved the basic components of Turkey’s health care system. Given that, how did these transformations and improvements reflect the goals of the health care system and what are the results of the HTP implementation? As previously stated, the performance of any health system, health policies or health reform programs are evaluated using four basic parameters, including improvements in health indicators, protection of citizens from financial risks, patient satisfaction with health services, and the sustainability of the health system.8

Improvements in Health Indicators

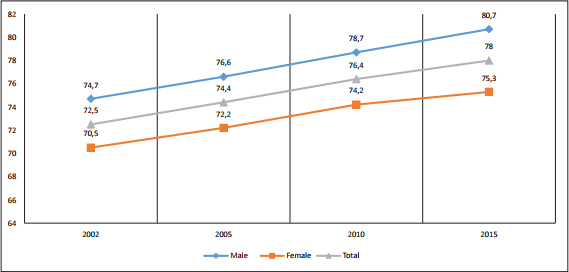

Over the last 15 years, Turkey has expanded its health services coverage and has improved basic health indicators.46 In addition to other indicators, the average life expectancy at birth has increased because of improvements in health services. The average life expectancy was 70.5 years in 2002 and 78 years in 2015 (Graph 14).

Graph 14: Average Life Expectancy at Birth (Years)

Source: General Directorate of Health Research47

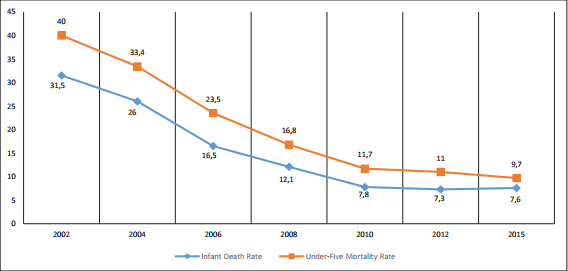

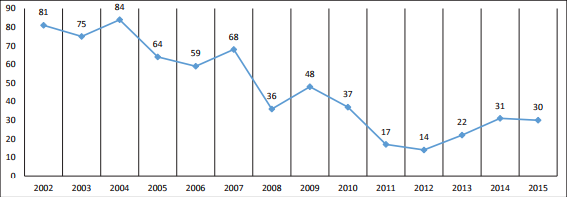

Significant improvements have also been achieved in Turkey in terms of reducing infant mortality and deaths of children under the age of five. In 2002, infant mortality was 31.5 per 1,000 live births, but dropped to 7.6 per 1,000 live births in 2015. Likewise, there has been a significant decrease in the number of deaths of children under the age of 5 (Graph 15).

Graph 15: Infant Mortality and Under-Five Mortality Rate per 1,000 Live Births

Source: General Directorate of Health Research48

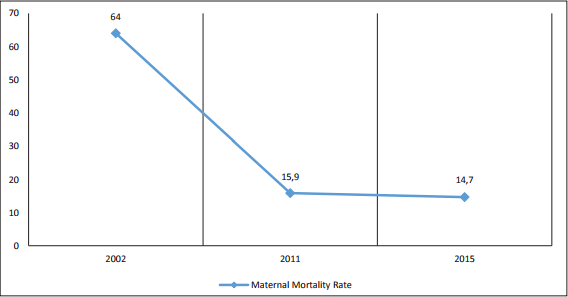

The maternal mortality rate in Turkey was 64 per 100,000 live births in 2002 and decreased to 14.7 per 100,000 live births in 2015 (Figure 16).

Graph 16: Maternal Deaths per 100,000 Live Births

Source: General Directorate of Health Research49

Financial Risk Protection

Additionally, the ratio of out-of-pocket health expenditures to total health expenditures has decreased. This ratio was 19.8 percent in 2002 and decreased to 16.6 percent in 2015 (Graph 17).

When more than 40 percent of annual income, excluding food expenses, is spent on health, it is described as catastrophic health expenditure. The percent of households with catastrophic health expenditures has recently declined (Graph 18).

Graph 17: Out-of-Pocket Health Expenditures (% of Total Health Expenditure)

Source: Akdağ50

Graph 18: Catastrophic Health Expenditures (Household, per 10.000)

Source: General Directorate of Health Research51

Responsiveness of and Satisfaction with Health Services

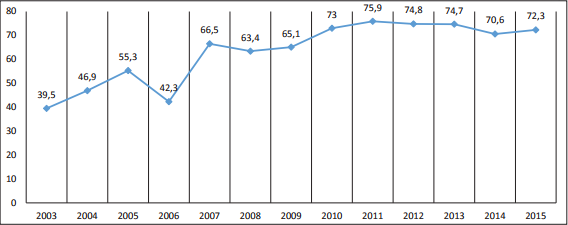

Graph 19, based on TURKSTAT Life Satisfaction Survey data, shows the rates of satisfaction with health services. The satisfaction rate approximately doubled from 39.5 percent in 2002 to 72.3 percent in 2015.

Graph 19: Overall Satisfaction with Health Services (%)

Source: General Directorate of Health Research52

Sustainability of the Health System: Financial Sustainability

The sustainability of a health system means its capacity to sustain its normal activities into the future.53 When reviewing the literature on health system sustainability, the first element mentioned is financial sustainability. There are no agreed-upon criteria for measuring and evaluating the financial sustainability of health systems. However, there are measures and evaluations based on indicators, such as health expenditures, income and resources, that are used to measure and evaluate whether a health system is financially sustainable.54

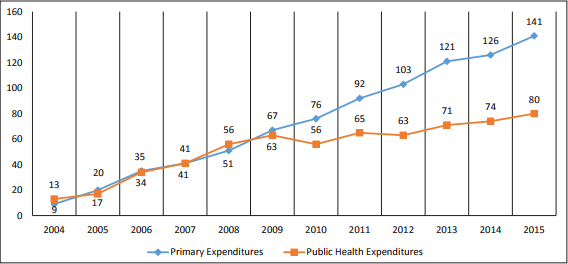

When we evaluate the financial sustainability of the Turkish health system based on health expenditures, we find that health expenditures have not changed over the past 15 years (Graph 11). However, primary public expenditures increased by 141 percent, while public health expenditures increased by 80 percent (Graph 20).

Graph 20: Primary Public Expenditures and the Increasing Ratio of Public Health Expenditures (%)

Source: General Directorate of Health Research55

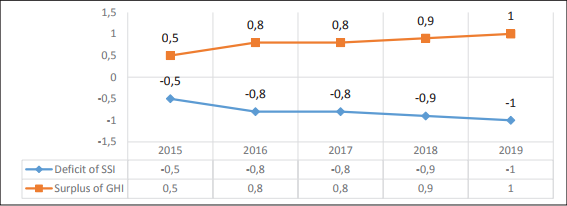

Graph 21: Deficit and Surplus of the Social Security Institution and General Health Insurance (% GDP)

Source: Ministry of Development56

Although the SSI has run a financial deficit for many years, the GHI branch of the SSI has produced a surplus. The primary cause of the deficit is long-term insurance, that is, pensions (Graph 21).

In Lieu of Results: Did the AK Party Succeed with Regard to the Health System? What Should Be Done Next?

As shown above, the AK Party government has improved almost all the components of Turkey’s health system over a 15-year period. Furthermore, these improvements have contributed positively to the prosperity of Turkish society, particularly its health status indicators.

How did the AK Party succeed with regard to the health system? The underlying reasons for its success are 1) the political stability of a single-party government, 2) the technical and financial support of the World Bank, 3) the EU integration process dynamics,57 4) economic growth, 5) commitment, 6) the strategic and systematic approach to health reform on the part of the MoH, 7) the existence of a comprehensive transformation strategy governed by a transformation team, 8) rapid policy transformation, 9) flexible implementation accompanied by continuous learning, 10) simultaneous improvements in the supply and demand of the health system, 11) high-level political and government support, and 12) political leadership.58

Notably, the leadership and support of President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan and, importantly, the leadership of Minister of Health Recep Akdağ, which included planning, positioning, and linking carefully, persistently, and effectively the strategy, people, and operations of which are the three basic processes of execution discipline,59 has been the primary factor for success. In addition, this success is due to 1) the elevation of the HTP to the international level through publications, model exports, and soft-power diplomacy, 2) the inclusion of the HTP as a priority in the AK Party’s electoral promises, propaganda, and transformation programs, and 3) the formation of intellectual capital accumulation in health policies and related areas.

What should be done next? It is important that the health care field be designed and continuously improved to create sustainable policies and strategies positively associated with the HTP and to cope with dynamic challenges, such as the ageing population, changes in disease prevalence, new technologies, increasing expectations and changing costs. This requires 1) the prioritization of policies and strategies that are sensitive to the health needs of the population, 2) the enactment of secondary legislation, 3) the continuation of political interest, support and commitment, 4) the maintenance of political and economic stability, 5) dedication to continuous improvement, and 6) the avoidance of populist initiatives and practices that threaten the system.60

Endnotes

- “58. Hükümet Acil Eylem Programı,” AK Party, (Ankara: 2003).

- “Sağlıkta Dönüşüm Programı,” Ministry of Health, (Ankara: 2003).

- “Everybody’s Business: Strengthening Health Systems to Improve Health Outcomes. WHO’s Framework for Action,” (Geneva: WHO, 2007).

- Hasan Hüseyin Yıldırım and Türkan Yıldırım, “Türkiye Sağlık Politikaları ve Reformları: Tarihsel Bir Bakış,” Türkiye Demokrasi Vakfı Enstitüsü Dergisi, (February 2010), pp. 28-33; Hasan Hüseyin Yıldırım and Türkan Yıldırım, “Türkiye Sağlık Reformları ve Politikaları: Politika Analizi Çerçevesinde Bir Değerlendirme,” in Mete Yıldız and Mehmet Sobacı (ed.), Kamu Politikası: Kuram ve Uygulama, (Ankara: Liberte, 2013).

- “OECD Health Systems Review: Turkey,” OECD and the World Bank, (Paris: 2008).

- “Sağlık Hizmetlerinin Sosyalleştirilmesi Hakkında Kanun,” Official Gazette, 12.01.1961/10705. Law No: 224, (Ankara: 1961).

- “Sağlık Hizmetlerinin Sosyalleştirilmesi Hakkında Kanun.”

- Yıldırım and Yıldırım, “Türkiye Sağlık Politikaları ve Reformları: Tarihsel Bir Bakış”; Yıldırım and Yıldırım, “Türkiye Sağlık Reformları ve Politikaları: Politika Analizi Çerçevesinde Bir Değerlendirme.”

- “OECD Health Systems Review: Turkey.”

- Yıldırım and Yıldırım, “Türkiye Sağlık Politikaları ve Reformları: Tarihsel Bir Bakış”; Yıldırım and Yıldırım, “Türkiye Sağlık Reformları ve Politikaları: Politika Analizi Çerçevesinde Bir Değerlendirme.”

- Yıldırım and Yıldırım, “Türkiye Sağlık Politikaları ve Reformları: Tarihsel Bir Bakış”; Yıldırım and Yıldırım, “Türkiye Sağlık Reformları ve Politikaları: Politika Analizi Çerçevesinde Bir Değerlendirme.”

- “OECD Health Systems Review: Turkey.”

- Yıldırım and Yıldırım, “Türkiye Sağlık Politikaları ve Reformları: Tarihsel Bir Bakış.”

- “OECD Health Systems Review: Turkey.”

- Yıldırım and Yıldırım, “Türkiye Sağlık Politikaları ve Reformları: Tarihsel Bir Bakış”; Yıldırım and Yıldırım, “Türkiye Sağlık Reformları ve Politikaları: Politika Analizi Çerçevesinde Bir Değerlendirme.”

- Yıldırım and Yıldırım, “Türkiye Sağlık Politikaları ve Reformları: Tarihsel Bir Bakış”; Yıldırım and Yıldırım, “Türkiye Sağlık Reformları ve Politikaları: Politika Analizi Çerçevesinde Bir Değerlendirme.”

- “58. Hükümet Acil Eylem Programı.”

- “Sağlıkta Dönüşüm Programı.”

- Yıldırım and Yıldırım, “Türkiye Sağlık Reformları ve Politikaları: Politika Analizi Çerçevesinde Bir Değerlendirme.”

- “Sağlıkta Dönüşüm Programı.”

- Yıldırım and Yıldırım, “Türkiye Sağlık Reformları ve Politikaları: Politika Analizi Çerçevesinde Bir Değerlendirme.”

- Recep Akdağ, “T.C. Sağlık Bakanlığı 2017 Yılı Bütçe Sunumu,” GNAT Planning and Budget Commission, (Ankara: 2016).

- Akdağ, “T.C. Sağlık Bakanlığı 2017 Yılı Bütçe Sunumu.”

- Akdağ, “T.C. Sağlık Bakanlığı 2017 Yılı Bütçe Sunumu.”

- Akdağ, “T.C. Sağlık Bakanlığı 2017 Yılı Bütçe Sunumu.”

- “Sağlık İstatistikleri Yıllığı 2015,” General Directorate of Health Research (SAGEM), (Ankara: 2016).

- “Sağlık İstatistikleri Yıllığı 2015.”

- “Sağlık İstatistikleri Yıllığı 2015.”

- “Sağlık İstatistikleri Yıllığı 2015.”

- Akdağ, “T.C. Sağlık Bakanlığı 2017 Yılı Bütçe Sunumu.”

- Akdağ, “T.C. Sağlık Bakanlığı 2017 Yılı Bütçe Sunumu.”

- Akdağ, “T.C. Sağlık Bakanlığı 2017 Yılı Bütçe Sunumu.”

- Akdağ, “T.C. Sağlık Bakanlığı 2017 Yılı Bütçe Sunumu.”

- Akdağ, “T.C. Sağlık Bakanlığı 2017 Yılı Bütçe Sunumu.”

- Türkan Yıldırım, Avrupa Birliği, Sağlık Çalışanları ve Türkiye: Serbest Dolaşım ve Potansiyel Göç, (Ankara: ABSAM, 2015).

- Akdağ, “T.C. Sağlık Bakanlığı 2017 Yılı Bütçe Sunumu.”

- Akdağ, “T.C. Sağlık Bakanlığı 2017 Yılı Bütçe Sunumu.”

- Akdağ, “T.C. Sağlık Bakanlığı 2017 Yılı Bütçe Sunumu.”

- “Sağlık İstatistikleri Yıllığı 2015.”

- Türkan Yıldırım, “Türkiye’de Sosyal ve Özel Sağlık Sigortacılığı,” in Hasan Hüseyin Yıldırım (ed.), Sağlık Sigortacılığı, (Eskişehir: Anadolu Üniversitesi AÖF Yayınları, 2012).

- “Sağlık İstatistikleri Yıllığı 2015.”

- “Sağlık İstatistikleri Yıllığı 2015.”

- “Sağlık İstatistikleri Yıllığı 2015.”

- Yıldırım and Yıldırım, “Türkiye Sağlık Reformları ve Politikaları: Politika Analizi Çerçevesinde Bir Değerlendirme.”

- Decree on the Organization and Duties of Ministry of Health and its Affiliates, Decree No: KHK/663, (November 2, 2017), Official Gazette, (Ankara: 2011).

- Yıldırım and Yıldırım, “Türkiye Sağlık Reformları ve Politikaları: Politika Analizi Çerçevesinde Bir Değerlendirme.”

- “Sağlık İstatistikleri Yıllığı 2015.”

- “Sağlık İstatistikleri Yıllığı 2015.”

- “Sağlık İstatistikleri Yıllığı 2015.”

- Akdağ, “T.C. Sağlık Bakanlığı 2017 Yılı Bütçe Sunumu.”

- “Sağlık İstatistikleri Yıllığı 2015.”

- “Sağlık İstatistikleri Yıllığı 2015.”

- James C. Knowles, Charlotte Leighton and Wayne Stinson, “Measuring Results of Health Sector Reform for System Performance: A Handbook Indicators,” Special Initiatives Report No. 1, Bethesda, MD: Partnerships for Health Reform, (1997).

- Özlem Özer, Hasan Hüseyin Yıldırım and Türkan Yıldırım, Sağlık Sistemlerinde Finansal Sürdürülebilirlik: Kuram ve Uygulama, (Ankara: ABSAM, 2015).

- “Sağlık İstatistikleri Yıllığı 2015.”

- “Orta Vadeli Program 2017-2019,” Ministry of Development, (Ankara: 2016).

- Yıldırım and Yıldırım, “Türkiye Sağlık Politikaları ve Reformları: Tarihsel Bir Bakış”; Yıldırım and Yıldırım, “Türkiye Sağlık Reformları ve Politikaları: Politika Analizi Çerçevesinde Bir Değerlendirme.”

- Enis Bariş, Salih Mollahaliloğlu and Sabahattin Aydın, “Healthcare in Turkey: From Laggard to Leader,” BMJ, Vol. 342, (2011), pp. 579-582; Recep Akdağ, “Lessons from Health Transformation in Turkey: Leadership and Challenges,” Health Systems and Reform, Vol. 1, No. 1 (2015), pp. 3-8; Rifat Atun et al., “Health Coverage in Turkey: Enhancement of Equity,” Lancet, Vol. 382, No. 9886 (2013), pp. 65-99; Rifat Atun, “Transforming Turkey’s Health System: Lessons for Universal Coverage,” The New England Journal of Medicine, Vol. 373, No. 144 (2015), pp. 1285-1289.

- Larry Bossidy and Ram Charan, “Execution: The Discipline of Getting Things Done,” Random House Inc., (2002).

- Yıldırım and Yıldırım, “Türkiye Sağlık Reformları ve Politikaları: Politika Analizi Çerçevesinde Bir Değerlendirme.”